National Styles

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

ANYONE WHO PERFORMS MECHANICAL work on motorcycles comes to understand that there are national styles in design. It takes a bit of reading, looking around and thinking to get some idea of what lies behind these styles.

What struck me about English motorcycles in the 1960s was the number of fasteners used and the stacks of extra washers under them. I was forever being embarrassed at the end of a project to have a few parts left over. When I got interested in aircraft engines, I saw that the British Rolls-Royce “Merlin” V-12, which played so large a part in WWII, was also held together with fasteners so closely spaced as to appear like stitches.

U.S.-made products were quite different. A story is told of Henry Ford, called to watch the first test of a new engine, being seriously offended at the carburetors being held in place by three bolts through a mounting flange. He wasn’t happy until a single, central screw held the carb in place. Why? Extra parts and paying people to install them add to cost. To this very day, U.S.-made engines retain their valve covers with the smallest-possible number of screws.

Taper fits were another peculiarity of classic British design. Many magnetos were driven by small roller chains whose sprockets fitted onto tapers. You were to loosely assemble the parts, rotate the engine to its firing point, do the same with the magneto and then seat the sprockets on their tapers with a “smart rap” from a small hammer. Then, you would do up the nuts holding the sprockets against their tapers. All done.

When I objected to my betters that hope was a poor substitute for sprockets positively located by keys, I got only a tolerant, superior smile and an assurance that, “Oh, she might wander a bit in the first 50 miles, but then she’ll bed in and the timing will never move.” Good luck.

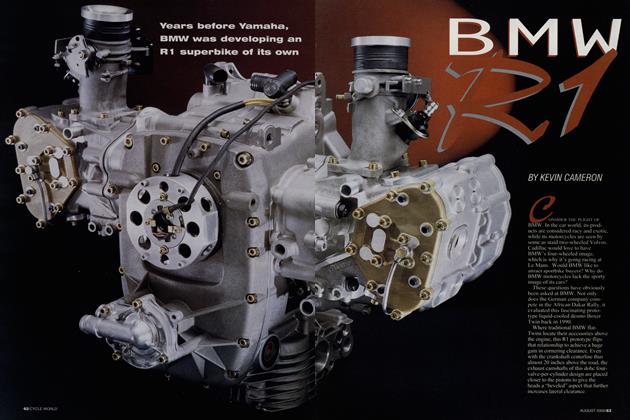

I had just enough experience with German machines to understand that a proper mechanic is always backed by a hydraulic press, an oven, a Dewar flask filled with liquid nitrogen and a wall covered with costly special tools. Pressand shrink-fits were common, and instructions were precise and demanding. There was only one correct way; all others were error. Only years later would I understand that late in the 19th century, Chancellor Bismarck had created a system of higher technical universities that provided the scientific and engineering know-how for Germany's planned and highly successful industrial revolution. There was no such thing as "established practice," as in the U.S. and Britain. There was only the correct way, which could be traced straight back to inflexible truths discovered by Newton, Leibnitz, Ostwald and others. I examined a German lathe. Its gears were retained by shaft keys, the keys were retained by screws and each screw was retained by a wire clip-belt-and-suspenders plus.

But back to the US. CW readers may recall this question, posed by former American Honda racing boss Gary Mathers: “The hay is cut, the sky is darkening but the baler is broken. Who do you get to fix the baler so the hay is in the barn before it rains? You get a farmer, not an engineer. An engineer will study the problem, and in six months, he’ll file a report. The farmer will find a way that may not be elegant, but it works.”

Along the same lines, Italians will tell you that the best engineers come from that country’s farming districts, where children grew up seeing adults making do, creating their own workable solutions but not necessarily according to Newton.

The differences between Britain and the U.S. go back to Britain’s traditionally large population of experienced craftsmen and “foreman fitters.” A “fitter” was someone who could make imperfect parts fit. U.S. labor, by contrast, was trainable but inexperienced. That meant “design for production” was serious stuff; the job was to design products that could only be assembled one possible way using the minimum number of parts, produced using the minimum number of machining processes. When we look at things that machinists and other perfectionists consider “nasty”— Phillips-head screws, self-tapping fasteners, pop rivets, stamped sheet metal parts with unpleasant sharp edges— we are looking at low production and assembly costs. Those low costs allowed U.S. manufacturers after the Civil War to say to then-dominant British pioneer industries, “We’ll take it from here, grandpa.” Low cost and satisfactory function made U.S. goods the world standard for many years.

The motorcycles now made in Britain by John Bloor under the Triumph name have been likened to Kawasakis in general design. But look at the engines: They are peppered with the traditional large number of case-cover screws. Did this come from stylists? Maybe. But it also could have come “from the blood”—it was always the British way.

There are plenty of exceptions. I think of former 250cc GP rider Martin Wimmer developing the chassis of his MZ Moto2 bike by twisting it with a long bar while watching the deflection with a dial gauge. Where he found the largest motions, he added a strut. Some might see this “farmer method” as American, but Wimmer and his MZ company are German. Here in the U.S., plenty of companies prefer engineers from a tech-school background. Why? Because they don’t have to teach them the practical stuff.

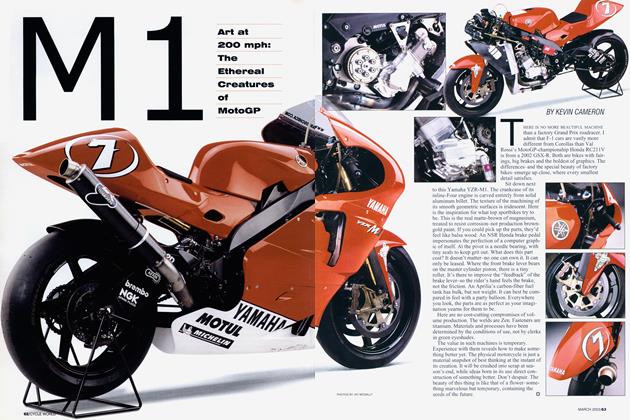

And Japanese design? Much of the original, post-war models were strongly influenced by German machines like DKW and NSU, but design-forproduction imposed its own rationality on the result. So, when I opened up my first Honda, Yamaha or Tohatsu, everything was neatly laid out, wellmade on the latest automatic machines and went back together quickly and easily. I saw the design of particular parts improved in steps, model by model, part of the Dr. Deming manufacturing concept (embraced in post-war Japan, rejected in the U.S. until around 1980) that an increase in quality is an increase in production.

Other nations are joining the worldmanufacturing community, adding their styles to design. Is there, or will there be, an Indonesian design style? A Brazilian style? About every fourth time I fly somewhere, it is aboard a Brazilian-made Embraer regional jet. Chinese goods are strongly influenced by Japanese models, as Japan began to move parts production to China in the late 1980s. Will globalization erase national styles?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue