RaceWatch

THE VIEW FROM INSIDE THE PADDOCK

WAYNE RAINEY MI5ANO WORLD CIRCUIT KEVIN SCHWANTZ

WAYNE'S WORLD

WAYNE RAINEY

Two decades after his paralyzing racing accident, three-time 500cc World [hampion Wayne Rainey talks about his crash, drive to win, and current health

Nic Coury

LETTING GO isn't something that Wayne Rainey does well. "I will never accept how things ended," he says, "but I have adjusted to what I missed, and that is the hardest part. There was a time I missed racing pretty hard, but I missed life in general." Twenty years ago, Rainey's life changed forever. The 32-year-old Californian was leading the Italian Grand Prix at the Misano Circuit, possibly en route to a fourth consecutive 500CC Grand Prix world title, when he crashed his factory Yamaha YZR500 at more than 120 mph.

Rainey spends 15 minutes describing that fateful 15 seconds. "In the first moment, I thought, ‘Damn, I've lost the world championship,' " he says. "In that particular corner, on that particular lap, on that particular day, I was at maximum bank angle and trying to get the bike back on line to start accelerating. When you're off throttle, all the weight is on the front tire, and I was in the danger zone of losing the front."

When Rainey opened the gas, the rear tire stepped out and he fell, sliding into the deeply furrowed gravel trap at the edge of the racetrack. "People say there is a right way to crash, and that is B.S.," he says. "The thought I had when I was flipping through the air was, `Don't try to stand up.' I was just in a ball.

"I felt this pop, and the next thing I knew, I was stopped. It felt like I had a huge hole in my chest. I told myself, ‘No matter how hurt you are, if you can stand up, you're going to be okay' "

Rainey recalls hearing the whir of the race going on around him. Then, everything began to fade to black. "Right before anyone got to me, all of a sudden, the pain was slipping away," he says. "I knew I might be dying, and that scared me."

Two weeks earlier, Rainey had crashed while practicing for the British Grand Prix at Donington Park. He hit his head, fractured vertebrae, and lost two fingernails. Worried he wouldn't be allowed to race, Rainey didn't disclose the most severe injuries. "I was competing for the world championship," he says. "If I didn't race, everything I had raced for that year would have been gone."

Rainey started the British GP and, despite being injured, exploited his unique ability to get an early lead. "Everyone thought I went pretty good on cold tires," he says, "so I thought if I could gear my bike to start in second gear, it would give me one less shift going into the first turn." Rainey led early and eventually finished second to his teammate, Luca Cadalora.

"I would not have raced [hurt] in my first couple of years," he says. "As a rookie, you don't want to risk hurting yourself or others. But that is what the championship meant to me. I was willing to risk those types of decisions to get a result."

Rainey says fear was his greatest motivator. "I didn't want to hurt myself, but I wanted to ride faster than the guy who was trying to beat me. Sol had to ride the bike in a certain way and, as it turns out, there were only a few guys who could do that. I was comfortable in the fast areas.

"If you made it to GP, you knew what it was like to ride injured. The thing is to understand how it can work for you. Your body has to be in the best shape it can be, and the only way you can do that is by training your mind. I remember being in school daydreaming about riding the bike a certain way.

"Riding a motorcycle with a lot of power and being able to make the bike do things you watched your heroes do, but now you could do, that was what it was about."

For Rainey, the close, fierce battle was important. "If it was going to get physical, I got physical," he says. "I liked the thrill of the whole process. There was nothing else for me."

Now, Rainey's battles are centered on his health. "My body is doing its own thing," he says. "I'm just along for the ride."

Earlier this year, that ride ended with several trips to the emergency room and six rounds of chemotherapy, which he finished in May. Diagnosis was polyarteritis nodosa, inflammation of the arteries, which become damaged when attacked by certain immune cells. It started eight months earlier with a series of short, but intense, headaches. Rainey likens the pain to getting hit with a ballpeen hammer.

"The first night, I took an aspirin and forgot about it," he says, "but after three nights, my wife, Shae, said, ‘There is something else wrong.' "

Early in the morning, they sped to the emergency room, but soon after, like every other night, the headache just went away. Next day, Rainey once again visited the ER. They took his blood pressure, which was at the level of a stroke victim. A CT scan revealed a blood clot in the renal artery feeding Rainey's right kidney. The doctor told him that about a third of the kidney had died.

Shortly thereafter, Rainey returned to the hospital. "I just couldn't get rid of the headache," he says. The doctor sent Rainey to Stanford Hospital for further tests. Another CT scan revealed his other kidney had failed. "The downside of being paralyzed is an inability to detect pain. There was a lot of damage, and the message couldn't be sent to the brain."

Rainey had a similar experience 15 years ago when his appendix burst. "You have to pay attention to what your body is doing," he says.

Rainey laughs when asked how he deals with life. "I'm always dealing with my injury," he says. "Like everybody, I have good and bad days, but you have to acknowledge what you can and can't do.

"Throughout my career, I prided myself on being as good as I could be, and success breeds not always the best decisions. It was the thrill of going for victory, trying to do something on the bike that the guys I was racing against couldn't do."

Rainey says he's now able to do nearly everything he did before the accident, "but just a little bit different, and that is how it is." ETMM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycling Manual

DECEMBER 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

DECEMBER 2013 -

Ignition

IgnitionSpied! Harley's New Indian

DECEMBER 2013 By Rishad Cooper -

Ignition

IgnitionDecember 1988

DECEMBER 2013 By Andrew Bornhop -

Ignition

IgnitionDetective Story

DECEMBER 2013 By Kevin Cameron -

Features

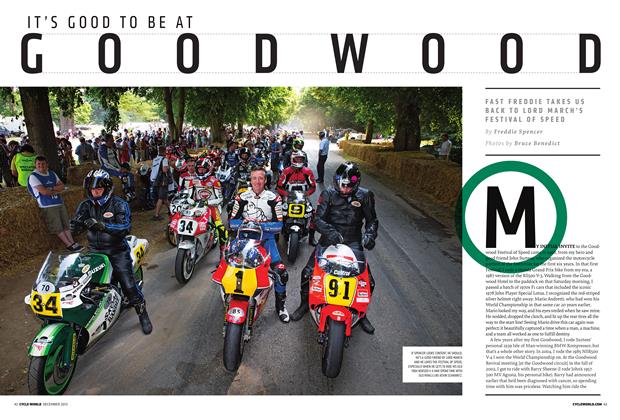

FeaturesIt's Good To Be At Good Wood

DECEMBER 2013 By Freddie Spencer