THE FIVE GREATEST

FEATURES

Choosing the five most influential motorcycles of all-time is no easy task. Which is why we picked six.

KEVIN CAMERON

SUPPOSE YOUR EDITOR KNEW YOU HAD been reading a lot of history and wanted to salvage something beyond antiquarian interest from that. Suppose he said, “It’s CW's 50th anniversary and we want to celebrate the history of motorcycles. Write me something about the five greatest machines of all time.” How could you pick?

You could let the public decide and choose machines like Edward Turner’s Triumph Speed Twin and the Honda 50cc step-through, which were the choices of hundreds of thousands of rid ers. You could look for pure innovation

and pick the early-days Peugeot parallel-Twin with its dohc and four valves per cylinder—although sadly, it just overheated and gave innovation a bad name. You could look for intensity of development and find it in the 1920s at AJS, early adopters of circulating oil systems, overhead cams and aluminum rather than iron for heads.

What I’ve decided to do instead is pick designs for their influence on later work; that way, I can start writing and stop dithering.

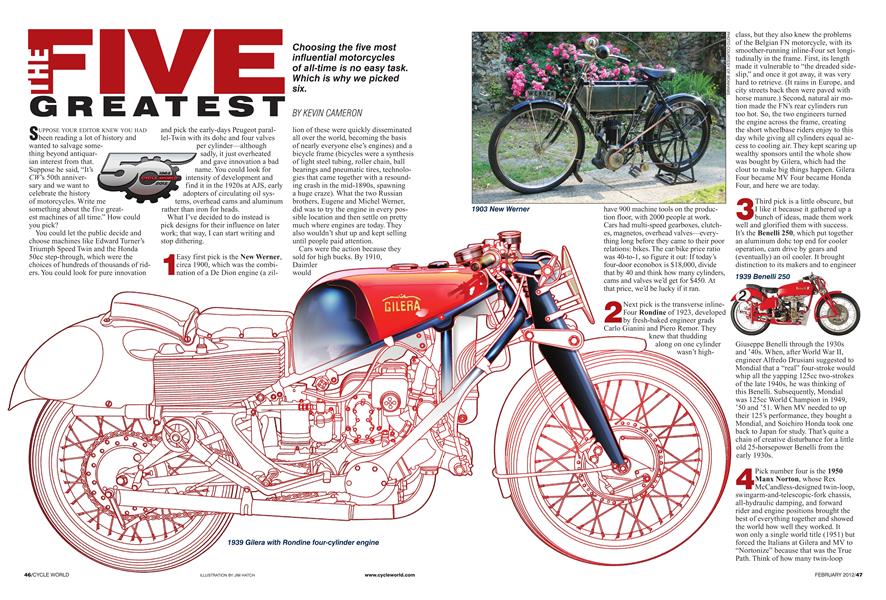

1 Easy first pick is the New Werner, circa 1900, which was the combination of a De Dion engine (a zillion of these were quickly disseminated all over the world, becoming the basis of nearly everyone else’s engines) and a bicycle frame (bicycles were a synthesis of light steel tubing, roller chain, ball bearings and pneumatic tires, technologies that came together with a resounding crash in the mid-1890s, spawning a huge craze). What the two Russian brothers, Eugene and Michel Werner, did was to try the engine in every possible location and then settle on pretty much where engines are today. They also wouldn’t shut up and kept selling until people paid attention.

Cars were the action because they sold for high bucks. By 1910, Daimler would

have 900 machine tools on the production floor, with 2000 people at work. Cars had multi-speed gearboxes, clutches, magnetos, overhead valves—everything long before they came to their poor relations: bikes. The car/bike price ratio was 40-to-l, so figure it out: If today’s four-door econobox is $18,000, divide that by 40 and think how many cylinders, cams and valves we’d get for $450. At that price, we’d be lucky if it ran.

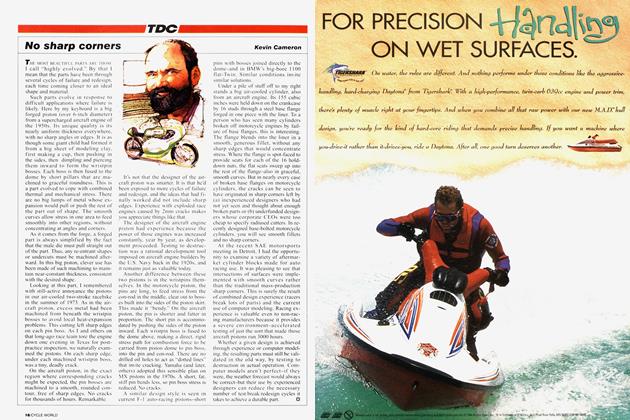

2 Next Four Rondine pick is the of transverse 1923, developed inlineby fresh-baked engineer grads Carlo Gianini and Piero Remor. They knew that thudding along on one cylinder wasn’t high-

class, but they also knew the problems of the Belgian FN motorcycle, with its smoother-running inline-Four set longitudinally in the frame. First, its length made it vulnerable to “the dreaded sideslip,” and once it got away, it was very hard to retrieve. (It rains in Europe, and city streets back then were paved with horse manure.) Second, natural air motion made the FN’s rear cylinders run too hot. So, the two engineers turned the engine across the frame, creating the short wheelbase riders enjoy to this day while giving all cylinders equal access to cooling air. They kept scaring up wealthy sponsors until the whole show was bought by Güera, which had the clout to make big things happen. Güera Four became MV Four became Honda Four, and here we are today.

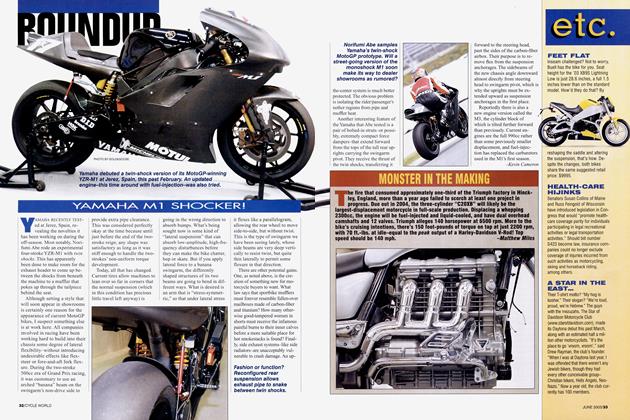

3 I Third like it pick because is a little it gathered obscure, up but a bunch of ideas, made them work well and glorified them with success.

It’s the Benelli 250, which put together an aluminum dohc top end for cooler operation, cam drive by gears and (eventually) an oil cooler. It brought distinction to its makers and to engineer

Giuseppe Benelli through the 1930s and ’40s. When, after World War II, engineer Alfredo Drusiani suggested to Mondial that a “real” four-stroke would whip all the yapping 125cc two-strokes of the late 1940s, he was thinking of this Benelli. Subsequently, Mondial was 125cc World Champion in 1949, ’50 and ’51. When MV needed to up their 125’s performance, they bought a Mondial, and Soichiro Honda took one back to Japan for study. That’s quite a chain of creative disturbance for a little old 25-horsepower Benelli from the early 1930s.

4Pick Manx number Norton, four whose is the Rex 1950 McCandless-designed twin-loop, swingarm-and-telescopic-fork chassis, all-hydraulic damping, and forward rider and engine positions brought the best of everything together and showed the world how well they worked. It won only a single world title (1951) but forced the Italians at Güera and MV to “Nortonize” because that was the True Path. Think of how many twin-loop

Norton-style “Featherbed” chassis have since been built; everyone had to copy it. And it chased away unhappy halfideas like girder, leading-link, slidingpillar or spring-hub designs.

5 Number five is the beastly Yamaha TZ750 because it made suspension, chassis and tire engineers suicidal. Their imaginations were awakened by the jangling alarm of desperation. The first try of 1974, TZ750A, was just as bad as the ghastly 1972 Kawasaki and Suzuki 750 racing Triples, which were the first wave of this revolution. Wobbling, weaving and shredding their tires, all three of these 750s were proof that skinny, hardrubber tires, door-closer shocks with three inches of travel and broom-handle frames were finished. The challenge was to make the 100-hp motorcycle controllable. I saw men desperate, sure that their racing careers were over, as they sat white-faced and shaking in their trackside lawnchairs. It was no better at the factories as the telexes piled up, telling how their new monsterbikes were being defeated by 350cc Twins.

Suddenly, change—hated and feared— became acceptable. Long suspension travel. Triangulated chassis bays. Wide, round-profile slick tires. Suspension that was actually track-tested and continuously improved. A revolution. Yamaha’s factory OW-31 of 1976 looked better, and a year later, the white-faced riders were given their careers back when the production TZ750D had the same features—Monoshock suspension, wide tires, the works.

6My last pick is the Honda RC211V, that company’s 990cc, V-Five four-stroke MotoGP bike. As the 1980s opened, the new big fourstrokes had the chassis, suspension and tires they needed to bring high performance to the masses (that’s us) because the big two-stroke racebikes had forced a revolution. That new synthesis brought us Suzuki’s GSX-Rs, Kawasaki’s Ninjas and Honda’s Interceptors, all of which represented a giant step forward from the lOOOcc, air-cooled four-stroke wobblers of the late 1970s.

But it’s easy to make a 100-hp, lOOOcc bike smooth enough to ride; just tune the engine as if it were going in a cruiser. What happens when we go for 200 hp? Honda found out as it developed the 21IV. A Honda test rider in the early going gave it a 2 out of 10 rating, saying, “The power cannot be used.”

In 2001, with the new MotoGP series less than a year away, problems persisted. “Improved throttle control is essential,” another test rider insisted. Heavy technology was deployed, but it was soon clear there wasn’t time to get automated systems right. So, the engine’s powerband was carefully tailored to what the rider could use—not driven to the limits of physics. Once smoothness was set as the goal, the new bike became quicker off corners than the previous two-stroke 500s. With velvety-smooth power, the rider could begin acceleration much earlier, and once the machine neared upright, all that displacement exerted its muscle. Smooth, usable power. Records fell right and left, and the 211 ’s riders dominated the sport for two solid seasons.

Since that time, competition tightened everything, forcing development of electronic torque smoothing, traction control, anti-wheelie and all the rest. But the process began with RC21IV It persuaded the engineers that the only useful power is power shaped exactly to fit what the tires can transmit.

That’s where we are today, when the 200-hp streetbike has become a rideable reality. What next?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

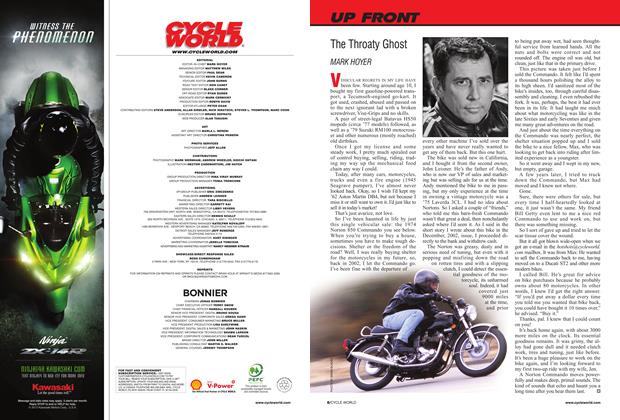

Up FrontThe Throaty Ghost

FEBRUARY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupWhat's the Two-Wheel World Coming To Anyway?

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

25 Years Ago February 1987

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Zeros

FEBRUARY 2012 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDaineses D-Air Street

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMilestones Along the Way

FEBRUARY 2012 By Paul Dean