LEANINGS

Triumph of the Killer Bees

PETER EGAN

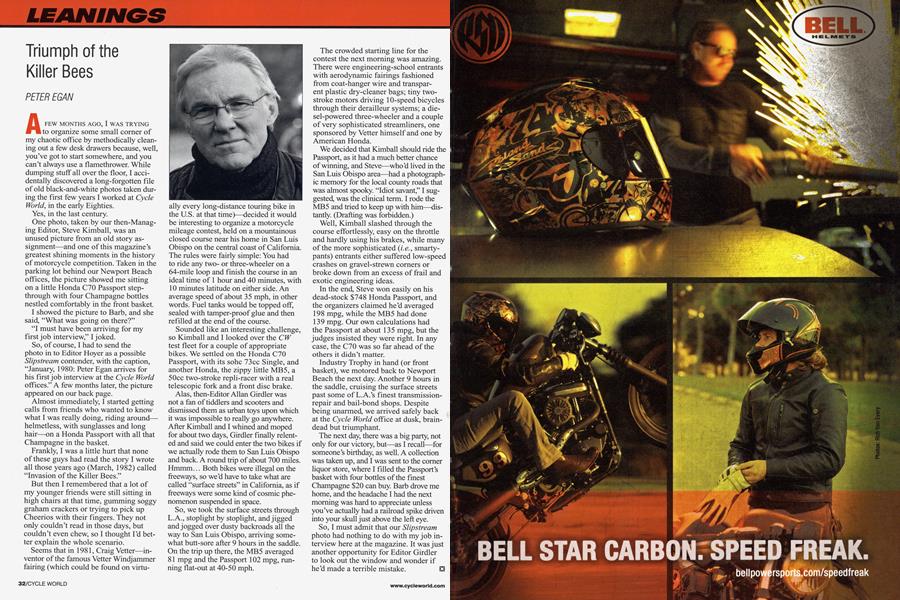

A FEW MONTHS AGO, I WAS TRYING to organize some small corner of my chaotic office by methodically cleaning out a few desk drawers because, well, you’ve got to start somewhere, and you can’t always use a flamethrower. While dumping stuff all over the floor, I accidentally discovered a long-forgotten file of old black-and-white photos taken during the first few years I worked at Cycle World, in the early Eighties.

Yes, in the last century.

One photo, taken by our then-Managing Editor, Steve Kimball, was an unused picture from an old story assignment—and one of this magazine’s greatest shining moments in the history of motorcycle competition. Taken in the parking lot behind our Newport Beach offices, the picture showed me sitting on a little Honda C70 Passport stepthrough with four Champagne bottles nestled comfortably in the front basket.

I showed the picture to Barb, and she said, “What was going on there?”

“I must have been arriving for my first job interview,” I joked.

So, of course, I had to send the photo in to Editor Hoyer as a possible Slipstream contender, with the caption, “January, 1980: Peter Egan arrives for his first job interview at the Cycle World offices.” A few months later, the picture appeared on our back page.

Almost immediately, I started getting calls from friends who wanted to know what I was really doing, riding around— helmetless, with sunglasses and long hair—on a Honda Passport with all that Champagne in the basket.

Frankly, I was a little hurt that none of these guys had read the story I wrote all those years ago (March, 1982) called “Invasion of the Killer Bees.”

But then I remembered that a lot of my younger friends were still sitting in high chairs at that time, gumming soggy graham crackers or trying to pick up Cheerios with their fingers. They not only couldn’t read in those days, but couldn’t even chew, so I thought I’d better explain the whole scenario.

Seems that in 1981, Craig Vetter—inventor of the famous Vetter Windjammer fairing (which could be found on virtually every long-distance touring bike in the U.S. at that time)—decided it would be interesting to organize a motorcycle mileage contest, held on a mountainous closed course near his home in San Luis Obispo on the central coast of California. The rules were fairly simple: You had to ride any twoor three-wheeler on a 64-mile loop and finish the course in an ideal time of 1 hour and 40 minutes, with 10 minutes latitude on either side. An average speed of about 35 mph, in other words. Fuel tanks would be topped off, sealed with tamper-proof glue and then refilled at the end of the course.

Sounded like an interesting challenge, so Kimball and I looked over the CW test fleet for a couple of appropriate bikes. We settled on the Honda C70 Passport, with its sohc 73cc Single, and another Honda, the zippy little MB5, a 50cc two-stroke repli-racer with a real telescopic fork and a front disc brake.

Alas, then-Editor Allan Girdler was not a fan of tiddlers and scooters and dismissed them as urban toys upon which it was impossible to really go anywhere. After Kimball and I whined and moped for about two days, Girdler finally relented and said we could enter the two bikes if we actually rode them to San Luis Obispo and back. A round trip of about 700 miles. Hmmm... Both bikes were illegal on the freeways, so we’d have to take what are called “surface streets” in California, as if freeways were some kind of cosmic phenomenon suspended in space.

So, we took the surface streets through L.A., stoplight by stoplight, and jigged and jogged over dusty backroads all the way to San Luis Obispo, arriving somewhat butt-sore after 9 hours in the saddle. On the trip up there, the MB 5 averaged 81 mpg and the Passport 102 mpg, running flat-out at 40-50 mph.

The crowded starting line for the contest the next morning was amazing. There were engineering-school entrants with aerodynamic fairings fashioned from coat-hanger wire and transparent plastic dry-cleaner bags; tiny twostroke motors driving 10-speed bicycles through their dérailleur systems; a diesel-powered three-wheeler and a couple of very sophisticated streamliners, one sponsored by Vetter himself and one by American Honda.

We decided that Kimball should ride the Passport, as it had a much better chance of winning, and Steve—who’d lived in the San Luis Obispo area—had a photographic memory for the local county roads that was almost spooky. “Idiot savant,” I suggested, was the clinical term. I rode the MB5 and tried to keep up with him—distantly. (Drafting was forbidden.)

Well, Kimball slashed through the course effortlessly, easy on the throttle and hardly using his brakes, while many of the more sophisticated (i.e., smartypants) entrants either suffered low-speed crashes on gravel-strewn comers or broke down from an excess of frail and exotic engineering ideas.

In the end, Steve won easily on his dead-stock $748 Honda Passport, and the organizers claimed he’d averaged 198 mpg, while the MB5 had done 139 mpg. Our own calculations had the Passport at about 135 mpg, but the judges insisted they were right. In any case, the C70 was so far ahead of the others it didn’t matter.

Industry Trophy in hand (or front basket), we motored back to Newport Beach the next day. Another 9 hours in the saddle, cruising the surface streets past some of L.A.’s finest transmissionrepair and bail-bond shops. Despite being unarmed, we arrived safely back at the Cycle World office at dusk, braindead but triumphant.

The next day, there was a big party, not only for our victory, but—as I recall—for someone’s birthday, as well. A collection was taken up, and I was sent to the comer liquor store, where I filled the Passport’s basket with four bottles of the finest Champagne $20 can buy. Barb drove me home, and the headache I had the next morning was hard to appreciate unless you’ve actually had a railroad spike driven into your skull just above the left eye.

So, I must admit that our Slipstream photo had nothing to do with my job interview here at the magazine. It was just another opportunity for Editor Girdler to look out the window and wonder if he’d made a terrible mistake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

AUGUST 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSometimes You Win

AUGUST 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupGet Healthy, Ride A Motorcycle

AUGUST 2011 By Philippe Devos -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1986

AUGUST 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBrammo Shifts Gears

AUGUST 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupOff the Reservation

AUGUST 2011 By Marc Cook