A Short History of Hitting My Head

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

JUST BEFORE WE TOOK OFF FOR Florida last week on a spring-break vacation, Barb’s sister Pam and her husband Richard called from Ft. Myers. “A good friend of ours named Scott Fischer is the local Harley dealer,” said Pam, “and when he heard you were coming to visit us, he said he could lend you a Harley while you’re here.”

“Great!” I said, eyeing the small carry-on suitcase I’d just begun to pack. “I’ll just bring a larger suitcase so we can take a couple of helmets along.”

“Oh, you don’t need a helmet in Florida,” she said. “It’s just like Wisconsin—we don’t have a helmet law down here.”

I held the phone and stared into space for a moment, scanning my memory for images of traffic in coastal Florida at the height of the winter tourist season. Lots of cars, many of them quite large and driven by elderly folks whose heads were not quite visible above their seatbacks, so that you were never really sure if the car ahead of you had a driver at the wheel or not. Often, it made no difference.

My parents lived in Florida for many years, and I used to joke (rather cruelly) that if you blew up a paper bag and popped it loudly, half the state population would die of a heart attack. Now that I’m a little closer to that age myself, it doesn’t seem quite as funny, but I still stand by the scientific principle.

Anyway, Florida didn’t seem like the best state in the Union in which to go helmetless, even if there was a certain warm-weather appeal to letting your freak flag fly and being free to do your own thing and ride your machine and not be hassled by the man, etc. I knew from previous trips that, while there were plenty of great places to ride in Florida, there would also be many pale yellow Lincoln Town Cars with white vinyl tops on their way to the Early Bird Senior Special at the Crab Shack, so you had to keep your wits about you. Also lots of half-lost visitors like me careening around.

“Well, I think I’ll bring helmets anyway,” I told Pam. “I just had my life saved by a helmet about six months ago, so I’m in kind of a helmet mood.”

I may have been overstating the case, as I have no proof that the helmet in question—a dual-sport Arai XD—actually saved my life, but I’d guess it did. If nothing else, it certainly saved me from a good spell in rehab, trying to guess (wrongly) how many fingers the therapist is holding up now.

It was a dirtbike crash in Wyoming last year that broke my foot and a bunch of ribs. During the accident, my helmet also took a pretty good bounce off a rock, and the impact was hard enough to leave my ears ringing for a few minutes. The helmet just had a small scuff mark and paint chip, and I didn’t even have a headache after the accident. Or maybe I did, but I was too busy grousing about my ribs and foot to notice. Anyway, I’m still here, after having my bell well and truly rung.

Actually, looking back at a lifetime of high adventure mixed with natural clumsiness, I would say helmets have spared me to ride another day at least three other times. One was a crash in the Barstow-to-Vegas Dual Sport ride, during which I flew over the handlebars of my XL500 and failed to attain lift, alighting amid some rocks on that portion of the helmet where my bare forehead would normally have been found. The other two were roadracing crashes—at Grattan and Riverside—where I lost the front end and low-sided, smacking my face into the pavement like somebody bobbing for blacktop, then slid for so long that I became bored and tried to stand up, falling again. In those last two cases, it was the chinbar on the helmet that took most of the impact.

You’d think those last two hits would have taught me a lesson, but—illogically—I still own a couple of openface helmets and wear them quite a bit for street riding on those bright, sunny days when my superstition and foreboding levels are especially low. I read an interview a few years ago with one of my heroes, four-time 500cc World Champion John Surtees, and he said he still prefers to wear an open-face helmet when doing track sessions and exhibition races, mainly because he’s always liked the openness of vision and hearing, the added peripheral awareness of his surroundings, that an open helmet provides.

I feel the same way. If I wear a fullface helmet, I adapt to it instantly and don’t give it a second thought. But when I switch to an open helmet, I feel strangely liberated and more attuned to what’s going on around me, like a guy who’s just put the convertible top down on his car.

Wearing no helmet at all adds yet another dimension of freedom, of course, unless it’s cold, windy, dusty, buggy or rainy, at which time that lack of helmet becomes just another of life’s many aggravations, like losing your gloves during a dogsled race. As so often happens here in the north.

Anyway, when it was time to pack for Florida last week, the helmet I chose was an open-face Shoei J-Wing with a dark-tinted flip-up shield. Never mind my long and violent history of chinsmacking, it just seemed like the right thing for Florida.

And it was. I picked up a nearly new Road Glide from my new friends at Harley-Davidson of Ft. Myers and was soon cruising down the wide boulevard that is Highway 41, headed toward Naples, with a short swing out toward Sanibel Island.

Palm trees along the highway reflected in the chromed gas cap on the Harley, and a light sea breeze wafted up the sleeves of my open Levi’s jacket. Bright red bougainvillea bloomed in front of homes with iridescently green lawns. The Big Twin was percolating nicely, with a relaxed and muted burble.

Ah, Florida. And warm air and sunlight and bridges and blue water passing by. It was my first ride in three months, and I’d almost forgotten what those motorcycles in my garage were for. They were for exactly this.

“Good to be here,” I said to myself. Then I thought about it for a moment and added that famous Keith Richards afterthought, “Good to be anywhere.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Japan In Need

JUNE 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAmerican Sport-Tourer

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

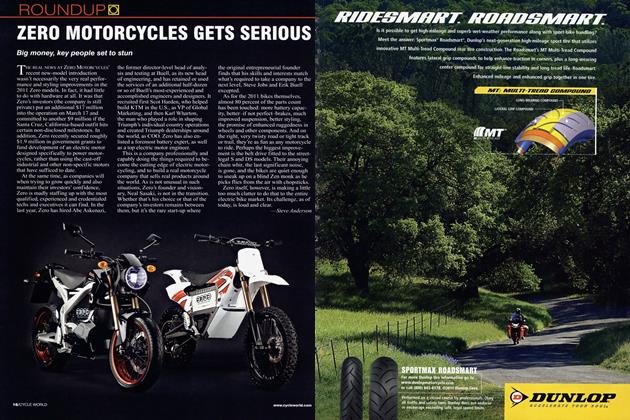

RoundupZero Motorcycles Gets Seriou

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

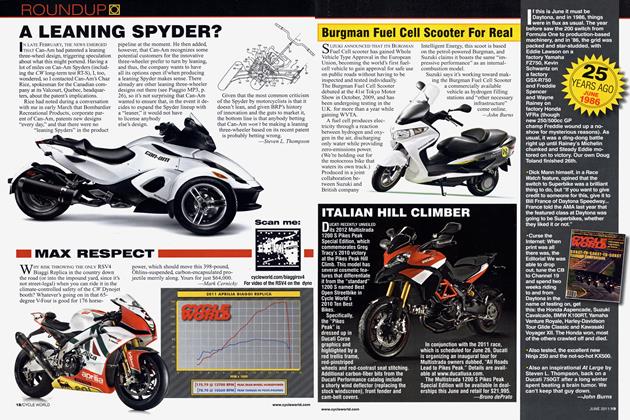

RoundupA Leaning Spyder?

JUNE 2011 By Steven L. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupMax Respect

JUNE 2011 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

RoundupBurgman Fuel Cell Scooter For Real

JUNE 2011 By John Burns