LEANINGS

Bonneville Fever

PETER EGAN

YESTERDAY-AS I WRITE THIS-WAS Black Friday, that infamous shopping day after Thanksgiving when consumers line up in front of shopping malls and try to kill each other. This morning’s paper reports that a fist-fight broke out between two women at Toys“R”Us, and one woman was taken away in handcuffs. The Christmas season starts early around here.

How blessed we motorcyclists are. While all this mayhem was taking place,

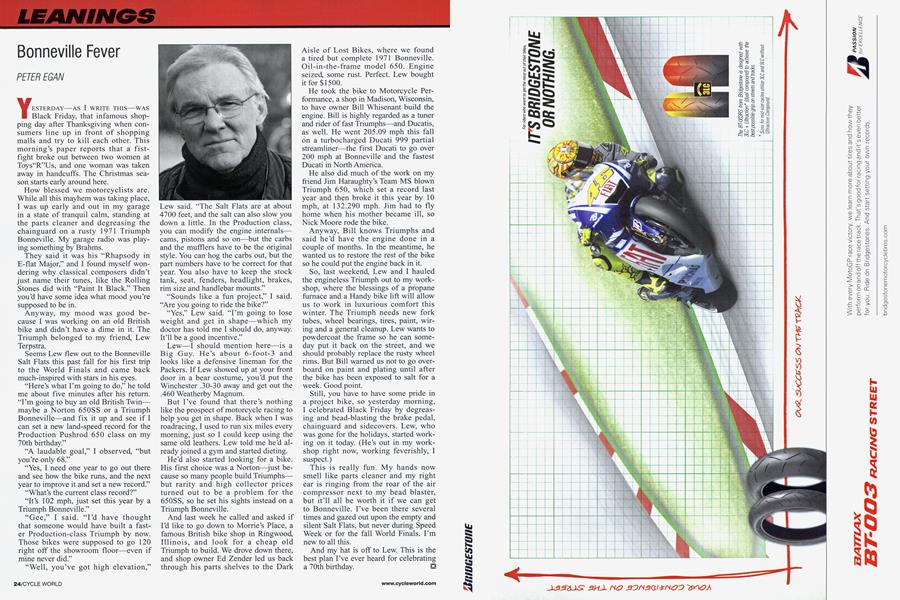

I was up early and out in my garage in a state of tranquil calm, standing at the parts cleaner and degreasing the chainguard on a rusty 1971 Triumph Bonneville. My garage radio was playing something by Brahms.

They said it was his “Rhapsody in E-flat Major,” and I found myself wondering why classical composers didn’t just name their tunes, like the Rolling Stones did with “Paint It Black.” Then you’d have some idea what mood you’re supposed to be in.

Anyway, my mood was good because I was working on an old British bike and didn’t have a dime in it. The Triumph belonged to my friend, Lew Terpstra.

Seems Lew flew out to the Bonneville Salt Flats this past fall for his first trip to the World Finals and came back much-inspired with stars in his eyes.

“Here’s what I’m going to do,” he told me about five minutes after his return. “I’m going to buy an old British Twin— maybe a Norton 650SS or a Triumph Bonneville—and fix it up and see if I can set a new land-speed record for the Production Pushrod 650 class on my 70th birthday.”

“A laudable goal,” I observed, “but you’re only 68.”

“Yes, I need one year to go out there and see how the bike runs, and the next year to improve it and set a new record.” “What’s the current class record?”

“It’s 102 mph, just set this year by a Triumph Bonneville.”

“Gee,” I said. “I’d have thought that someone would have built a faster Production-class Triumph by now. Those bikes were supposed to go 120 right off the showroom floor—even if mine never did.”

“Well, you’ve got high elevation,” Lew said. “The Salt Flats are at about 4700 feet, and the salt can also slow you down a little. In the Production class, you can modify the engine internals— cams, pistons and so on—but the carbs and the mufflers have to be the original style. You can hog the carbs out, but the part numbers have to be correct for that year. You also have to keep the stock tank, seat, fenders, headlight, brakes, rim size and handlebar mounts.”

“Sounds like a fun project,” I said. “Are you going to ride the bike?”

“Yes,” Lew said. “I’m going to lose weight and get in shape—which my doctor has told me I should do, anyway. It’ll be a good incentive.”

Lew—I should mention here—is a Big Guy. He’s about 6-foot-3 and looks like a defensive lineman for the Packers. If Lew showed up at your front door in a bear costume, you’d put the Winchester .30-30 away and get out the .460 Weatherby Magnum.

But I’ve found that there’s nothing like the prospect of motorcycle racing to help you get in shape. Back when I was roadracing, I used to run six miles every morning, just so I could keep using the same old leathers. Lew told me he’d already joined a gym and started dieting.

He’d also started looking for a bike. His first choice was a Norton—just because so many people build Triumphs— but rarity and high collector prices turned out to be a problem for the 650SS, so he set his sights instead on a Triumph Bonneville.

And last week he called and asked if I’d like to go down to Morrie’s Place, a famous British bike shop in Ringwood, Illinois, and look for a cheap old Triumph to build. We drove down there, and shop owner Ed Zender led us back through his parts shelves to the Dark Aisle of Lost Bikes, where we found a tired but complete 1971 Bonneville. Oil-in-the-frame model 650. Engine seized, some rust. Perfect. Lew bought it for $1500.

He took the bike to Motorcycle Performance, a shop in Madison, Wisconsin, to have owner Bill Whisenant build the engine. Bill is highly regarded as a tuner and rider of fast Triumphs—and Ducatis, as well. He went 205.09 mph this fall on a turbocharged Ducati 999 partial streamliner—the first Ducati to go over 200 mph at Bonneville and the fastest Ducati in North America.

He also did much of the work on my friend Jim Haraughty’s Team MS blown Triumph 650, which set a record last year and then broke it this year by 10 mph, at 132.290 mph. Jim had to fly home when his mother became ill, so Nick Moore rode the bike.

Anyway, Bill knows Triumphs and said he’d have the engine done in a couple of months. In the meantime, he wanted us to restore the rest of the bike so he could put the engine back in it.

So, last weekend, Lew and I hauled the engineless Triumph out to my workshop, where the blessings of a propane furnace and a Handy bike lift will allow us to work in luxurious comfort this winter. The Triumph needs new fork tubes, wheel bearings, tires, paint, wiring and a general cleanup. Lew wants to powdercoat the frame so he can someday put it back on the street, and we should probably replace the rusty wheel rims. But Bill warned us not to go overboard on paint and plating until after the bike has been exposed to salt for a week. Good point.

Still, you have to have some pride in a project bike, so yesterday morning, I celebrated Black Friday by degreasing and bead-blasting the brake pedal, chainguard and sidecovers. Lew, who was gone for the holidays, started working on it today. (He’s out in my workshop right now, working feverishly, I suspect.)

This is really fun. My hands now smell like parts cleaner and my right ear is ringing from the roar of the air compressor next to my bead blaster, but it’ll all be worth it if we can get to Bonneville. I’ve been there several times and gazed out upon the empty and silent Salt Flats, but never during Speed Week or for the fall World Finals. I’m new to all this.

And my hat is off to Lew. This is the best plan I’ve ever heard for celebrating a 70th birthday. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue