RACE WATCH

The New Wrecking Crew

Recent Honda MotoGP bikes have been fast and powerful, but now they're controllable

KEVIN CAMERON

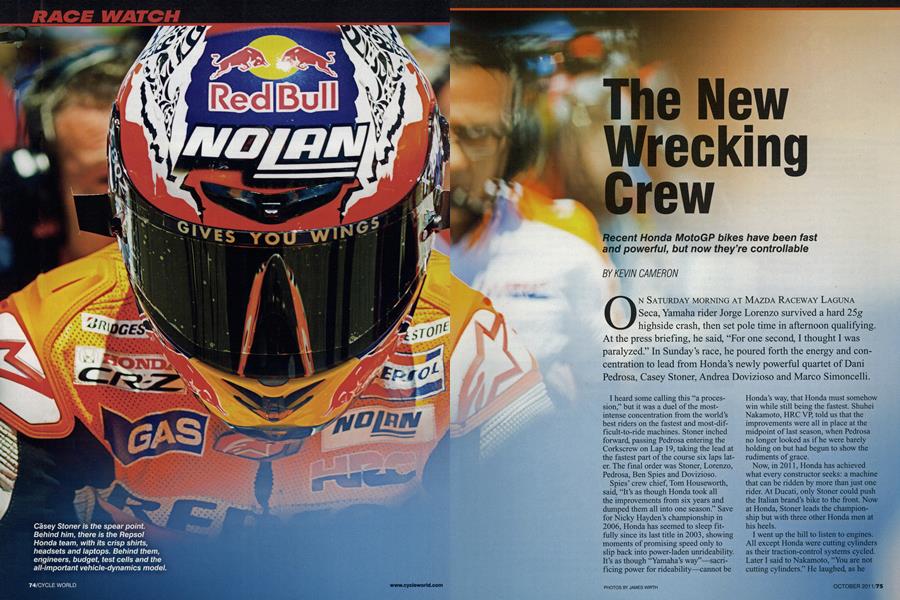

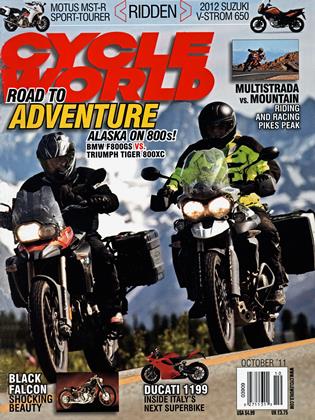

ON SATURDAY MORNING AT MAZDA RACEWAY LAGUNA Seca, Yamaha rider Jorge Lorenzo survived a hard 25g highside crash, then set pole time in afternoon qualifying. At the press briefing, he said, "For one second, I thought I was paralyzed." In Sunday's race, he poured forth the energy and concentration to lead from Honda's newly powerful quartet of Dani Pedrosa, Casey Stoner, Andrea Dovizioso and Marco Simoncelli.

I heard some calling this “a procession,” but it was a duel of the mostintense concentration from the world’s best riders on the fastest and most-difficult-to-ride machines. Stoner inched forward, passing Pedrosa entering the Corkscrew on Lap 19, taking the lead at the fastest part of the course six laps later. The final order was Stoner, Lorenzo, Pedrosa, Ben Spies and Dovizioso.

Spies’ crew chief, Tom Houseworth, said, “It’s as though Honda took all the improvements from six years and dumped them all into one season.” Save for Nicky Hayden’s championship in 2006, Honda has seemed to sleep fitfully since its last title in 2003, showing moments of promising speed only to slip back into power-laden unrideability. It’s as though “Yamaha’s way”—sacrificing power for rideability—cannot be

Honda’s way, that Honda must somehow win while still being the fastest. Shuhei Nakamoto, HRC VP, told us that the improvements were all in place at the midpoint of last season, when Pedrosa no longer looked as if he were barely holding on but had begun to show the rudiments of grace.

Now, in 2011, Honda has achieved what every constructor seeks: a machine that can be ridden by more than just one rider. At Ducati, only Stoner could push the Italian brand’s bike to the front. Now at Honda, Stoner leads the championship but with three other Honda men at his heels.

I went up the hill to listen to engines. All except Honda were cutting cylinders as their traction-control systems cycled. Later I said to Nakamoto, “You are not cutting cylinders.” He laughed, as he

so often does. “How do you modulate torque?” I then asked. He laughed again. “Are you leaning out the mixture?” “Could be,” said Nakamoto,

MotoGP’s man of mystery.

Honda has a new zero-delay gearbox (“A Shift in Changing Gears,” July, 2011), which engages the next-higher gear without first disengaging the gear that is driving. The act of doing so then kicks out the lower gear. I asked, “What is the service interval for this gearbox?” Smiling at his usual private joke, Nakamoto replied, “I cannot say.

Because I don’t know!”

Ducati now has its similar gearbox working well, and Yamaha is said to be close to deploying its own design. In this series, with many sharp minds in command of powerful resources, no advantage remains private for long.

Honda hired Livio Suppo away from his job as team manager at Ducati. I wanted to hear his views on the dangers of having four strong riders who can take points from each other.

“The more we win, the more we are happy,” he said. “The more strong riders you have, the more possibility you have to win.”

Okay, I get it: It’s policy, and you can say nothing. Later in the conversation, he said, “At the moment, I am not involved in team organization. I am more involved in sponsorship.”

I was eager to talk with Hirohide Hamashima, formerly Bridgestone’s Formula One tire manager. I asked about the technology behind riders setting fastest lap near the end of races, a big change from the 1990s when Mick Doohan would spend the last 10 laps of a GP “just sliding around” on fatigued tires. Hamashima tapped the eraser of a pencil on the table.

"It was interesting to meet Andrea Dovizioso, who spoke very fast about MotoGP bikes.

`MotoGP bike is very difficult to ride, very precise. Tires and chassis are so stiff."

“If I do this 100 times or 1000 times, this rubber will break—fatigue breakage. But [today’s] racing rubber never ever like that. Very strong for stress, molecule never ever broken by the stress.”

Bridgestone has devoted much research to achieving strong chemical bonds between rubber chains and ultrafine silica particles. Formerly, rubber depended for its tensile strength upon make-and-break adsorption bonding to tiny dispersed particles of carbon black (the reason tires are black). With ultrafine silica particles added, greater tensile strength can be combined with the softness necessary to make the mostintimate contact with the pavement texture. Softness plus the new tensile strength equals the amazing lean angles we are now seeing in MotoGP.

Talk of the paddock was the continuing inability of Ducati riders Nicky Hayden and Valentino Rossi to get the carbonchassis 2011 GP11 and “11.1” (a 2012 prototype with an 800cc engine) bikes to competitive lap times. Lack of front-end feel (warning of impending breakaway) and inability to finish the comer (poor line-holding during off-comer acceleration) were the main problems.

Hayden said, “With this bike, the first warning you get is you’re lying on the ground.” When I asked Stoner about this, he said, “The bike would feel really good, then it would go and you wouldn’t know why.”

Stoner spoke more about feel, about warning. “It’s all about the vibration.

No vibration in the bike, it feels greasy; you’ve got no contact with the ground. When it feels right for me is that you can feel the tire actually walking on the tarmac, on the bits of stone. [On either side of that], if there’s too much chatter and it’s skipping across, or the opposite, when it’s too smooth.”

It was interesting to meet Andrea Dovizioso, who spoke very fast about MotoGP bikes. “MotoGP bike is very difficult to ride, very precise. Tires and chassis are so stiff.” He agreed with Simoncelli, who said, “For me, 125 and 250 were better school for this bike, better than Moto2. The Moto2 is lessextreme bike, more like streetbike, more easy to ride.”

Both men described production-based bikes as sliding around in a forgiving, greasy kind of grip that absorbs mistakes—much as Kenny Roberts has described the 500cc two-strokes of his era, 1978-83.

People mentally combine Simoncelli’s big hair and erratic riding, but he is a clear speaker. “When you feel exactly what is happening on the front wheel, you understand where you can push, where is the limit. Without it, you can push, you feel you can push more, and you lose the front. Sometimes, when you are very close to the limit, try to brake harder, the front—the bars— become light.”

MotoGP’s huge achievement since 2002 is that when bikes are at maximum lean angle, their virtual powerbands can deliver torque smooth enough not to upset tire grip, so the bike accelerates. Stoner prefers little traction control so that he can use rear tire spin to steer, but this can backfire in the form of excessive tire temperature (a high, 290 degrees Fahrenheit one week earlier at the Sachsenring’s many corners) that cuts peak grip and slows lap times.

Simoncelli said, “At the beginning of the year, I was using more [traction control], but now we try to reduce. This gives a more direct feeling with the throttle and improves the consumption.” Cutting sparks wastes fuel.

Mr. Nakamoto seems to have gotten Honda moving in MotoGP after a period of internal disorganization. (He would surely disagree with this statement; he is like the law professor who said, “State me a proposition and I’ll deny it!”) Honda’s “NSR years”—Freddie Spencer through Mick Doohan—were directed by men of the old order, men like Mr. Honda himself. After that came an interim of political correctness when bosses could no longer shout or throw

cylinder heads and be obeyed by terrified juniors. Three years ago, Honda hired vehicle-dynamics software-writer Andrea Zugna away from Yamaha. Nakamoto said, “Last year, we change control system. This system is made by Honda Formula One. This system is growing every day, because engineering is growing. We are still working.”

The result is what we see: still the most-powerful machine in the paddock—a constant Honda goal—but now stabilized, rideable to top level by four different strong riders. That has forced Lorenzo to ride with utmost concentration and very close to the limit this year. The most dangerous thing a top rider can do is try to win on a bike that is almost fast enough.

The point nobody talks about is that next year, liter bikes must race on the same 21 liters of fuel that are barely enough for today’s 800cc engines. How will they do it? Romantics hope the new 1000s mean a return to sideways cowboy riding, but that won’t happen because it wastes essential assets: fuel and tires. The tempting way is to voluntarily limit peak rpm to Superbike-like numbers—just over 14,000. Another is to add yet more econo-car technology, things like stratified-charge lean combustion, Miller cycle operation or even multi-mode operation. The most-effective of fuel-saving technologies, direct fuel injection, is prohibited by present technical rules.

The fast-approaching 1000s will race with tires in line at gravity-defying lean angles just as today’s 800s do, but they will pack even more electronics with which to manage ever-more-complex fuel-use strategies. E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBattle of the Dust

OCTOBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

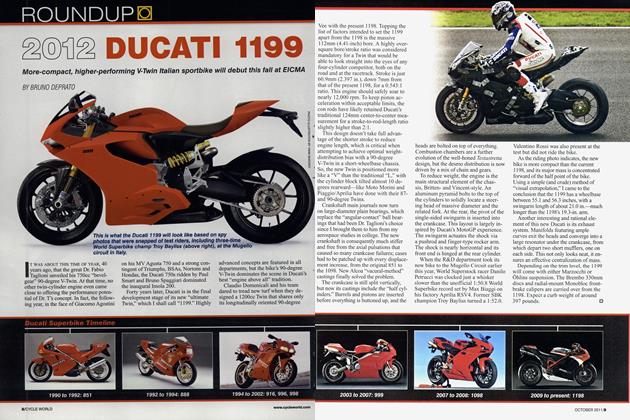

Roundup2012 Ducati 1199

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Nsf250r Moto3 Contender

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Mv Agusta F3 Serie Oro

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

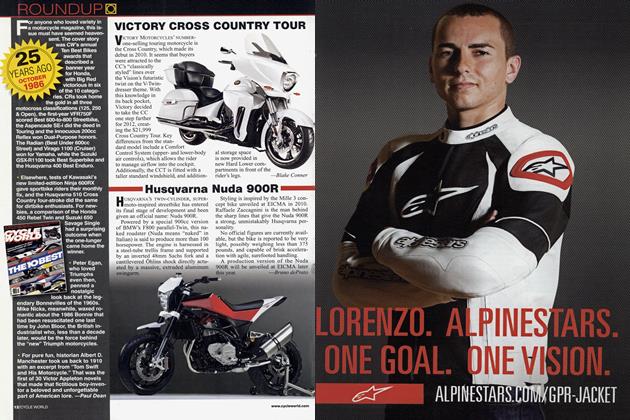

Roundup25 Years Ago October 1986

OCTOBER 2011 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupVictory Cross Country Tour

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner