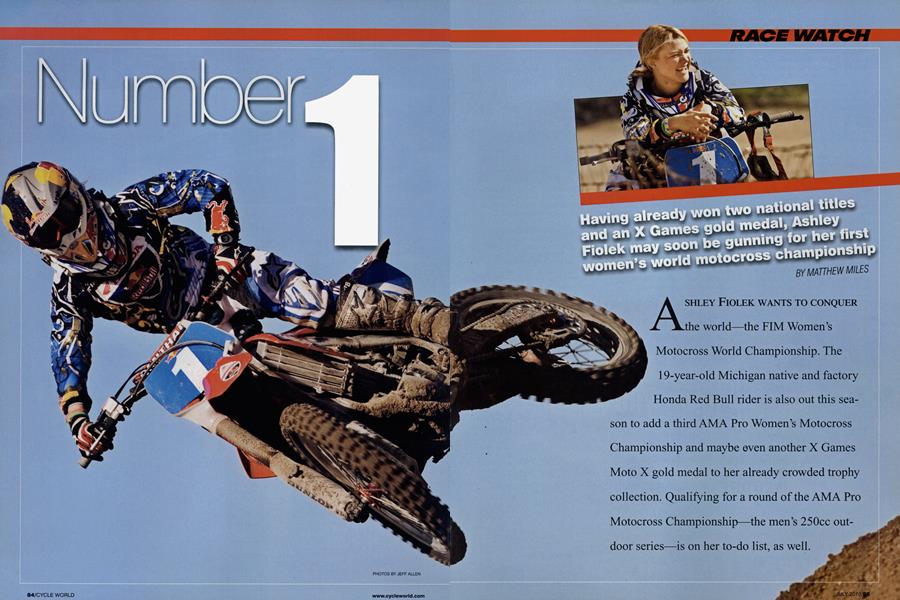

Number1

RACE WATCH

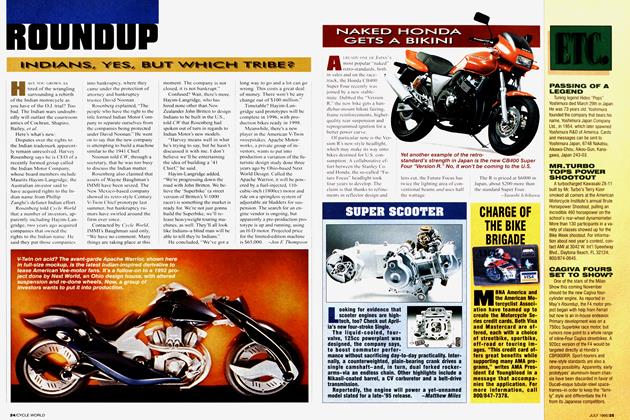

Having already won two national titles and an X Games gold medal, Ashley Fiolek may soon be gunning for her first women's world motocross chapmpionship

MA1THEW MILES

ASHLEY FIOLEK WANTS TO CONQUER the world-the FIM Women's Motocross World Championship. The 19-year-old Michigan native and factory Honda Red Bull rider is also out this season to add a third AMA Pro Women's Motocross Championship and maybe oven another X Games Moto X gold medal to her already crowded trophy collection. Qualifying for a round of the AMA Pro Motocross Championship-the men's 250cc out door series-is on her to-do list, as well.

Who is this barrier-smashing teen? Actually, Fiolek’s story parallels that of many professional male racers. She began riding at 31/2 years old on a Yamaha PW50, spurred on by the enthusiasm for the sport shared by her familygrandfather, father and mother.

“Jim and I grew up trail-riding in Michigan,” said Fiolek’s mother, Roni. “So riding is in Ashley’s blood. As soon as she could ride on her own, it was non-stop. We took her to a Supercross race [at the Pontiac Silverdome], and she was hooked. We thought, ‘Cool. Ashley likes riding, too.’ But she took it to another level.” Fiolek entered her first race—the annual “Spring Fling” at Log Road in Coldwater, Michigan—at age 7. Pitted against 11 other riders in the pee-wee race, she finished fourth, good enough for a trophy. “This was my first taste of winning, and I liked it,” Fiolek wrote in her just-published autobiography, Kicking Up Dirt. “I think that’s when my parents realized that I wasn’t kidding around when I said I wanted to race.” Here’s where Fiolek’s story takes a sharp turn: She didn’t verbalize her feelings to her parents; she signed

them—as in American Sign Language.

Fiolek is deaf.

“It took so long to find out that Ashley was deaf,” recalled Roni. “We were told so many things—that she was retarded, for example. We were really frustrated. Once we found out that she was deaf, it was like,

‘Oh, thank goodness.’”

Neither Fiolek nor her parents consider deafness a handicap.

“Jim and I cringe when people say ‘hearing impaired,”’ said Roni. “She’s deaf.

She’s not ashamed of

it. Her struggles have been more of a girl in a man’s sport than being deaf. Nobody held her back because she was deaf.”

Shortly after Fiolek’s race debut, her family moved to St. Augustine, Florida, where she enrolled in the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind—the largest school of its kind in this country.

Everything the Fioleks had read in dicated that deaf children should be immersed in deaf culture. But no one at the school understood or related to Fiolek's racing, so she began to make more hearing friends. Eventually, she drifted away from the deaf community. More problematical, because her family was frequently on the road traveling to races, Fiolek missed a lot of school. “When Ashley was halfway through ninth grade, I got called into the principal’s office,” said Roni. “With a state school, you have to follow the

state’s rules. You’re only allowed so many absences, and it just wasn’t going to work. So we began home schooling.” While she was in deaf school, Fiolek was a good student. She was motivated and tested well. Grammar wasn’t a

high priority because Fiolek and her fellow classmates “spoke” ASL, which doesn’t use smaller parts of speech, such as articles. That Fiolek was deaf didn’t concern the home-schooling program. She had to re-learn English, and school became a struggle. Fiolek completed most of her high school work through a correspondence program in Pennsylvania. She earned her degree through an accredited online course called On Track.

The Fioleks aren’t wealthy. Jim is a computer programmer and Roni is a stay-at-home mom. When Ashley said she wanted to be the best motocrosser and needed their help, the family dedicated itself and its resources to her racing. Making ends meet was tough, though; no matter if the rider is male or female, the costs associated with national-level competition—bikes, fuel, hotels, spare parts, food, etc.—are identical. “Everybody in motocross at the amateur level has second mortgages on their houses,” said Roni. “We were fortunate that we didn’t have to go to that extreme.”

Jim’s company let him work on the road. So, when the Fioleks were away from home, he was usually working. If they stayed at a hotel, Ashley and her mother had to leave the room so Jim could hold conference calls. Internet

access wasn't easy to find, either. The Fioleks often hung out all day at Star bucks and other WiFi hotspots. Other times, Fiolek and her mother were alone.

“One time, Jim drove us from Florida to Texas in our motorhome and then flew home to work,” remembered Roni. “We were there by ourselves for I don’t remember how long. Kicker, Ashley’s younger brother, was with us, too. He was still little; I could stick him in a walker, but that didn’t last long.

“We didn’t have a mechanic, and I had to work on Ashley’s bike. I could tighten the chain, add gas and oil, but that was about it. She would ride all day, and I would work on the bike. By the end of the day, we were exhausted. Looking back, though, it was fun. We worked hard, and it’s good to see how things turned out.”

Though still a teenager, Fiolek is a driving force for equality in women’s motocross. While high-profile male riders moved on to the professional ranks, leaving big-time events such as the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships and the Winter National Olympics—better known as the Mini O’s—for the next generation, Fiolek (having already bagged a dozen national titles) and her fellow female competitors were expected to continue racing those events.

After Fiolek won her first professional national title in 2008 riding under the Women’s Motocross Association (WMA) banner, she was invited to the AMA’s end-of-season amateur awards ceremony. Fiolek realized the situation would never change until someone made a stand. Number-one plate already in hand, she declined the invitation. “If we ride together, we should celebrate together.”

Last year, MX Sports purchased the rights to the Women’s Motocross Association National Championship from series founder Miki Keller and incorporated it into the AMA Pro Motocross Championship. “This is huge news for the sport of women’s motocross here in the U.S.,” Fiolek announced. “We all know that Miki has worked tirelessly to improve the environment for women in this sport.” Differences remain—fewer rounds, shorter motos, smaller paychecks—but progress is evident. Two years ago, for example, girls couldn’t even park in the same place as the boys. “At Hangtown,” recalled Fiolek’s mother, “we were back in some rocks somewhere. We weren’t even allowed in the pits.” Last season,

however, the girls were right there with the guys.

American Honda has supported Fiolek with bikes and parts for a number of seasons. Last year, she became the first female factory rider, teaming with top male stars Davi Millsaps, Andrew Short, Ben Townley and Ivan Tedesco on the Honda Red Bull squad.

“Ashley is an exceptional rider,” said team manager Erik Kehoe, a top former rider himself. “We also liked her energy, the electricity around her. She always has a big smile on her face.

“Sometimes, it’s

difficult for athletes to connect with fans when they’re signing autographs. Some riders sign away and don’t even look up from the table, like it's an as sembly line. Ashley looks at the kids and smiles, gives them `high-fives.'

That’s what we’re about. We want our athletes to be role models. Ashley is a perfect fit.

“Until Ashley came along, I hadn’t had the opportunity to get to know some of her competitors—Vicky Golden, Sherri Cruz and a few others. They’re great girls and tough competitors.”

Last season, Fiolek had already tallied 10 wins when the eight-round AMA/WMA series made its final stop at Steel City Raceway in Delmont, Pennsylvania. Looking to wrap up her second title, she crashed while running second in the first moto. Fiolek remounted, rode slowly past the mechanics area and pointed at her shoulder.

“We told her, ‘The championship is on the line—you’ve got to finish,”’ remembered Kehoe. Fiolek stayed on track and finished seventh, scoring enough points to hang onto the number-one plate.

Four days later, surgeons inserted a plate and six screws to fix Fiolek’s broken collarbone. “You don’t think of a little, blond-haired girl like Ashley as being really tough,” said Kehoe. “Her collarbone was snapped in two.” >

Fiolek may be the fastest woman in this country, but she still has work to do if she is going to be world champion. At the opening round of the 2010 FIM Women’s Motocross World Championship in Sevlievo, Bulgaria, riding a borrowed CRF250R, Fiolek posted the fourth-best timed lap on the mile-plus-long, natural-terrain track in practice, qualified fifth-quickest, was seventh in the morning warm-up and finished fourth and sixth, respectively, in the two-moto format. Red Bull KTM rider Stephanie Laier, from Germany, won both races by a large margin. Fiolek, fifth overall in points at presstime, was the top-placing Honda rider and the sole American.

If her schedule allows, the 5-foot-2,

110-pound Fiolek would like to race more of the longer-moto, rougher-track rounds of the FIM WMX series. And don’t forget the X Games. “I know X Games is a big event for Ashley,” said Kehoe. “If she wants to do that, we will support her.”

X Games poster-child Travis Pastrana taught Fiolek to backflip on a minibike—after just three attempts. “It’s hard to imagine the petite, deaf girl with the warm smile could possibly be a gold medalist in the physical sport of Supercross,” he said. “But Ashley has found a way to turn what most would consider negatives into her biggest assets.”

Possible world championship and X Games glory aside, winning another AMA/WMA title is top priority for American Honda. “Ashley is using the European stuff as a warmup to our series,” said Kehoe. “I don’t think the world championship is in the cards for her right now.”

Ditto qualifying for a men’s national. “That’s a great goal, and it would a great personal achievement,” he added. “I have no doubt she could qualify, but the races are longer and she would have to completely change her training. Right now, we want to focus on the class she is currently racing.”

Through it all, Fiolek has come full circle with the deaf community. She garnered national attention two years ago with a T-Mobile Sidekick endorsement (she taps out 800-plus text messages per day). Noise-cancelling headphone-maker Able Planet and IPRelay-source Purple Communications have reached out to her, as well. She’s also toed the water as a motivational speaker at deaf schools and with her mother headlined the 2009 AMA International Women & Motorcycling Conference. “To give back to the deaf community was always Ashley’s dream,” said Roni. “She wants to inspire others.”

Right now, Fiolek’s central focus is motocross. “There are a lot of girls on factory teams this year, and I think that’s great,” she said.

“We don’t need to settle for anything because we work just as hard as the men do. It’s a tough battle because a lot of people out there think that women shouldn’t be racing or we don’t deserve as much time as the guys out on the track.

“We are all doing a sport that we love. I think as long as the guys and girls are out there working hard, everyone needs to be recognized and respected.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRisk Management

JULY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupThrottle By Wire

JULY 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World

JULY 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupWill the Real F4 Please Stand Up?

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupMiddleweight Eight!

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1985

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner