SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Honda pumper carb

I have a problem with my 1972 Honda CB500. The number 4 cylinder’s carb shoots a short burst of fuel out of the overflow drain tube about every 20 seconds, whether the motor is running or not (and the petcock is in the on position). It’s not just a gravity-driven flow; the fuel shoots out like it’s under pressure. The motor runs fine while it’s leaking fuel. I disassembled the carbs for a cleaning but the only things I found dirty (partially clogged) were the slow jets. The float travel is within spec and the float actuates normally, as do the needle and little plunger on the end of the needle. I switched the needle, seat and float with carb number 3, but fuel still shoots out of the number 4 drain tube. I tried bending the needle-height tab on the float way up so the needle would close sooner, and that significantly reduced the amount of fuel leaking, but it still drips out a few drops about every 20 seconds. I’m stumped as to what to look for next. I’m ready to install a whole set of spare carbs that need a serious cleaning first. Got any suggestions on what’s causing the fuel leak?

Carl Sampson Posted on www.cycleworld.com

Aí think what you have described is the result of not one but two problems. One is obvious, which is that fuel enters the number 4 carburetor’s float bowl after the float has pushed its needle and seat into the closed position. But I think that problem is being caused by a faulty vent in the gas cap. As fuel in the gas tank heats up—whether due to the heat of the engine, exposure to the sun or any other normal cause—it expands, potentially creating a considerable amount of pressure inside the tank. The vent in the gas cap, however, is intended to let that pressure escape before it can build to a point where it effectively acts like a fuel pump. Since the tank is higher than the carbs, gas normally flows into your CB500’s float bowls only as the result of gravity, and the float mechanisms are capable of blocking the flow of fuel only at that low level of pressure. So if considerably higher pressure builds up in the tank, it is easily capable of forcing the needle to unseat and let excess fuel enter the float bowl. The gas then emerges from the overflow tube in short spurts because as soon as the needle unseats, allowing a small amount of fuel to enter, the pressure in the tank is relieved just enough to let the needle reseat and stop the flow until the pressure sufficiently rises again.

For me, though, the real mystery here is why this overflow condition only occurs with the number 4 carb, even after you have swapped its float, needle and seat with those from another carb that does not spurt gas. Without being able to inspect the fuel system on your Honda, I have no rational explanation for that phenomenon.

In any event, I suggest you simply try opening the flip-up gas cap before starting the bike and leave it open while running the engine in neutral until the engine warms. If no fuel exits the overflow tube, you will have found the cause of the problem.

Cranky cranker

QI have a 2007 Suzuki Boulevard M109R, and when I try to start the bike, it many times will act like the battery is dead. If I let off the starter button and try it again, the engine will start. This happens more often when the engine is hot. Please let me know if you have ever heard of this problem, and if there is any solution. Ray HitSOn

Ocala, Florida

A Yes, I have heard of it, and it is a relatively common occurrence on big V-Twin engines. The 1783cc Ml09 has an exceptionally large (4.4-inch) bore and a fairly high (10.5:1) compression ratio, a combination that makes the electric starter work hard just to push the bike’s two huge pistons through the compression stroke. So if, when the engine was last shut off, one of those pistons ended up right at the end of the intake stroke and beginning of the compression stroke, the starter can stall. It does so because starting at that point, it is unable to give the crankshaft enough rotational inertia to force that piston through the resistance of compression. It’s much like what happens when you try to drive a nail into a piece of wood: You can’t do it if you start with the hammer already touching the head of the nail, but it’s an easy task if the hammer starts some distance away and gets a “run” at the nail.

When that first attempt at starting the engine fails, the piston has already partially compressed the air in the cylinder; so, when the starter disengages, that compressed air pushes back on the piston, causing the crankshaft to rotate backwards, and the piston tends to end up in a different position than it was in before the first attempt. Thus, when the starter is engaged again, it usually can successfully push the piston through that initial compression cycle as the crank gains enough inertia to continue overcoming further compression strokes.

If your bike’s battery is not in topnotch condition, this “failure to launch” will happen more often than usual. Same goes for the electric starter: Due to small but normal differences in manufacture, some starters produce slightly more cranking torque than others. If the output of your starter is on the low side, the frequency of this occurrence will be greater than usual.

Suzuki Ml09s are not the only bikes that often stall the starter motor due to compression resistance. It occasionally happens on other large-displacement Japanese V-Twins and even more frequently on Harley-Davidsons. In fact, many modified Harley engines are equipped with compression releases that must be either manually actuated before starting or that automatically open when the starter is engaged. Even then, some of those hot-rodded engines need to be fitted with aftermarket starter motors that have more torque than the Stockers so they can overcome the resistance of high compression.

Unchained malady

QHOW can I tell if the chain is worn out on my 2004 Honda 919? I bought the bike two years ago when it had 9000 miles on it, and I’ve only added another 5000. The chain has started getting noisy, even though I regularly adjust and lube it, but I don’t think a chain should be shot after just 14,000 miles. Is there a sure way to determine if the chain requires replacement? The economy has hit me just as hard as anyone else, and I don’t want to spend the money on a new chain (and they aren’t cheap!) if I don’t have to. Kenny Johnston Davenport, Iowa

A Checking chain wear is pretty easy, Kenny. After you lube and properly adjust the chain (about an inch to an inch-and-a-half of up-and-down freeplay measured on the bottom run of the chain halfway between the countershaft and the rear wheel), grab the chain with your thumb and forefinger at the very back of the rear sprocket and pull it directly backward like you were trying to pull it off the sprocket. If you can lift any link more than about halfway off of its sprocket tooth, the chain is finished and should be replaced.

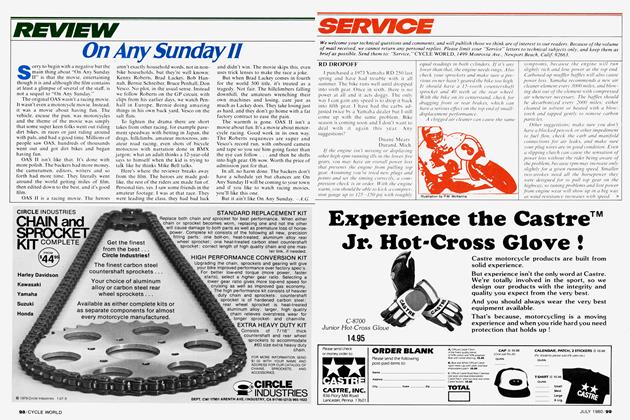

At the same time, you need to check the condition of the sprockets. As a chain wears, the effective distance between the individual rollers gradually increases ever so slightly, but it’s enough nonetheless to accelerate wear of the sprocket teeth. Instead of remaining down in the valleys between the teeth during the strong pull of acceleration, worn rollers instead start climbing up the backsides of the teeth. And as the chain continues to stretch, the rollers gradually ride up far enough to cause the tops of the teeth to wear in a way that looks like little ocean waves, as shown in the accompanying illustration that compares a new sprocket with a worn-out one. Even the pull of the chain on trailing throttle will wear a sprocket, causing the valley between teeth to become even wider.

CandidCameron

Q Thank you for the great Laguna Seca MotoGP article (“Strength Renewed”) you wrote in last October’s issue. I was amazed at how fast Dani Pedrosa’s Honda was on the front straight. Some laps, it looked like he was outaccelerating second place by four bikelengths (a gap often lost on the back side of the course). What had Honda done to gain such speed? Dayn Mansfield

Atascadero, California

A Even without electronic aids, there are limits to how much power we can build into a motorcycle—the reason being that the “harder” we tune the engine (long cam timings with a lot of overlap, heavy reliance on intake and exhaust tuning), the harder-to-use it becomes because its torque curve has regions in which torque rises so steeply that it’s very tricky to accelerate off corners.

Installing a new chain to run on worn sprockets is a waste of time and money. The chain will then wear much more rapidly, causing the need for yet another new chain—as well as both sprockets— to arrive much sooner.

Back in the days of 500cc two-stroke GP bikes, every maker could have built engines producing 200 horsepower with no trouble, but it would have made their bikes slower around the track. An outfit called Swissauto did produce a 500 with 200 hp some time ago, and in testing, it was the slowest bike on the track because the power was too tricky to be usable. We now have electronic torque-smoothing, anti-wheelie and anti-spin technologies, and these systems have limits just as riders do, but they are higher limits. This means that, once again, the harder you tune the engine, the greater the chance that actual powerband features will overcome the electronics and give trouble to the rider, at least on occasion.

Since the beginning of MotoGP we’ve seen this happen again and again. Ducati entered the series with a lot of power, but it took them 2 or 3 years to make its bike

Gear sk-sk-skipping

QMy 2001 Suzuki GSX-R600 with 20,000 miles on it has been adult-ridden and never raced. Over the summer, it suddenly started

usable enough that people could win races on it. Honda raised their power in 2004, and it made its bikes visibly harder to ride (and Yamaha won the title with at least 4 mph less top speed than Honda).

Last season, Honda’s engineers were fixing a lot of little things, and maybe their confidence in their electronics was such that they were able to put a little more power in the engine, thinking it would be usable. At Laguna, it was, and Pedrosa won. At Indianapolis, however, he was having to work very hard to keep the pace, and he eventually tipped over.

Then there’s the Ducati, which was never easy to ride. Toward the end of the season, Nicky Hayden got much closer to competitive lap times; but as powerful as that bike was, the rough edges of its torque curve did show through all the electronics enough that they bit the rider from time to time.

-Kevin Cameron

feeling like the rear wheel slips for a fraction of a second when I shift around 9000 rpm. I’ll shift it from first to second or from second to third just above 9000 rpm, and when it hits 9000 in the next gear, it feels like the rear sprocket has slipped and then reconnected. The dealer believes a clutch pack for around $300 is the solution. How do I know for sure that this will fix the problem? Jim Ryan

Huntley, Illinois

A Based on your description of the symptoms, I don't believe that the problem is in the clutch pack. If you have not already checked your Gixxer's drive chain, I suggest you do so as described in the Service letter titled "Unchained malady" on page 68. If the chain and sprockets are excessively worn, the chain may indeed be skipping when you shift. Replacing those com ponents should remedy the problem.

If the chain and sprockets are in good condition, the problem most likely is in the gearbox. Such “skipping” generally is caused by the shift forks for the affected gears being worn and/ or bent, or by rounded-off engagement dogs on the gears themselves—or

both. In any case, disassembly of the engine and inspection of the gearbox cluster is required.

There is a slight chance that the problem is only with the shift mechanism and not the gearbox, which would make for a much less-expensive repair. The shift linkage may not be moving the affected gears far enough to fully engage. The engagement dogs on the gears are slightly undercut, which tends to draw them together once they make contact with one another; so they sometimes initially reject one another, resulting in a brief “skip,” but then re-engage and draw themselves fully together. I doubt this is the problem with your Suzuki, but it’s worth investigating anyway.

Gettin’ wiggly with it

QI recently purchased a 2000 Triumph Trophy 1200 with 12,000 miles on it. I have noticed that if I take my hands off the bars with only engine braking slowing me down, from 40 mph to 20 mph, the bars and front end will vibrate quickly back and forth for a few moments before smoothing out again. I have had the bike up to 100 mph a few times and have done some fairly aggressive cornering and braking, and the bike feels solid. As always, when I purchase a bike, I have my trusted mechanic go over it, and he checked the bearings in the front wheel and the steering head, assuring me that all is fine. The only thing he didn’t check was the wheel balance. As long as I have my hands on the bars during this transition period, I feel no vibration. Should I be concerned or would this just be the dynamics of the bike with the transition of the engine slowing it down as opposed to applying the brakes?

Doug Stanger Maple Ridge, British Columbia, Canada

A Engine braking has nothing to do with this condition, other than allowing you to slow the bike without your hands on the bars. The front-end wiggle you describe occurs on many different makes and models of motorcycles, and it usually is more exaggerated with worn tires than with newer ones. In fact, some bikes that don’t wiggle at all on brand-new tires will start to do so once the tires rack up some miles. The cause of the wiggle is a combination of effects that is too complex to explain in any detail here, but it involves some bikes’ steering geometry, steering mass, front-tire characteristics and the self-centering effect of front-wheel trail that can be energized at certain speeds.

This phenomenon only occurs when you let go of the bars because when your hands are on the grips, they serve as dampers that prevent the wiggle from initiating. So, even when some undulation on the road surface causes the front end to twitch ever so slightly, that movement is so small that you don’t notice it, and its energy is absorbed by the mass of your arms, preventing the movement from evolving into a full-fledged wiggle.

The bottom line? Don’t worry about moderate speed, hands-off wiggles; they’re common and pose no safety hazard—especially if you keep your hands on the bars. U

Got a mechanical or technical problem and can’t find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663;

2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651 ; 3) e-mail it to CWIDean @aol.com-, or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do provide enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. Include your name if you submit the question electronically. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

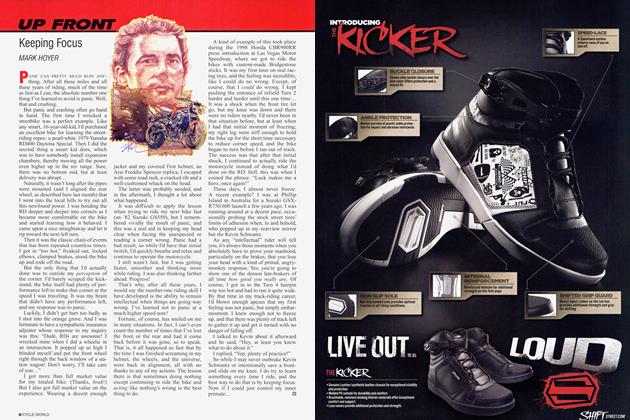

Up FrontKeeping Focus

MARCH 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAsphaltfighters Stormbringer: Autobahn Extraordinaire

MARCH 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupEddie Lawson: 20 Years Later

MARCH 2010 By Nick Ienatsch -

Roundup

RoundupEtc...

MARCH 2010 -

25 Years Ago March 1985

MARCH 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

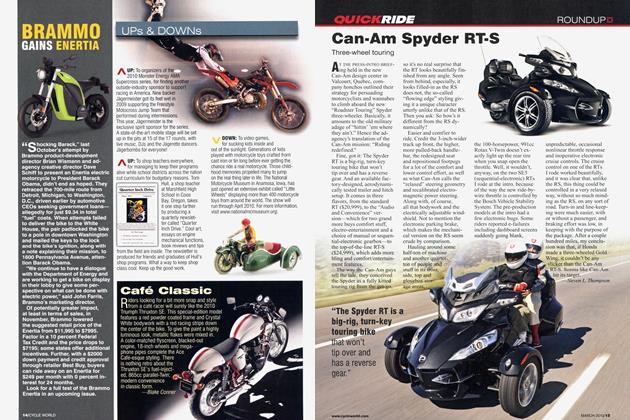

RoundupBrammo Gains Enertia

MARCH 2010