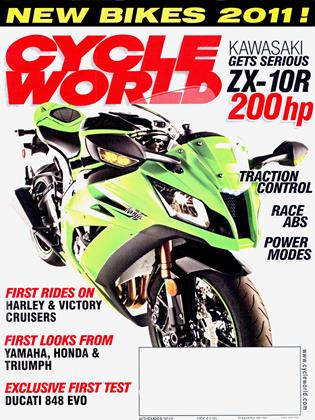

2011 Kawasaki ZX-10R

Team Green goes ballistic in the electronics wars

PAUL DEAN

SPECIAL TECH PREVIEW

"IT'S NOT HOW MUCH POWER A MOTORCYCLE HAS,” SAID ROB Taylor of Kawasaki’s Tech Services Department, “it’s how much power the rider of that motorcycle can use. That’s what we have worked long and hard to accomplish with the new ZX-10R; that’s what this bike is all about.”

Taylor later seemed to contradict himself by stating that the 2011 ZX will make “a little more power than the 2010 model,” which, at 160-plus rear-wheel hp (and claimed at-the-crank numbers about 20 points higher), already was one of sportbiking’s most prodigious producers of wild, untamed horses. But once you learn about all the electronic technology that Kawasaki has packed into this new superbike, Taylor’s claim starts making perfect sense.

In his tech presentation, which was exclusive to Cycle World, Taylor was unable to provide specific horsepower numbers, or claimed dry weight and MSRP. “What we have now are pre-production bikes,” he said, “so several things still have to be sorted out. We have a target power number we’d like to achieve and think we can lose more than 20 pounds compared to last year’s bike [435 lb. dry on the CWscales], but we won’t know for sure until the production specs have been finalized.”

What he does know is that the ’ 11 ZX-10R is equipped with a threeposition Power Mode selector, and that each Mode provides three levels of real, honest-to-God traction control. Combine that with the most sophisticated ABS ever offered on a production motorcycle, and the picture starts snapping into razor-sharp focus.

Of those electronic rider aids, the most intriguing is S-KTRC (SportKawasaki Traction Control), and it differs substantially from the “standard” KTRC used on the company’s Concours 14 sport-tourer. The Cone’s system was very simple and intended for rider safety, whereas the ZX-1 OR’s was designed to, in Kawasaki’s own words, “enable riding at the edge of traction.. .help riders push harder on the track by maximizing acceleration go faster.. .and as long as effective traction is maintained, allow power slides and power lifts” (wheelies).

For the 1 OR to perform in such an unprecedented manner for a streetbike, S-KTRC receives input from more sources than do systems from other manufacturers. Ducati’s traction control, for example, uses vehicle acceleration and front-to-rear wheelspeed differential to determine how much rear-tire slippage to allow, while BMW’s employs front/rear wheel-speed comparison and a bank-angle sensor. But Kawasaki’s system makes decisions based on front/rear wheel-speed differential, engine rpm, throttle position and rate of acceleration. It then analyzes that data not just to adjust ignition timing to limit rear-tire slippage, it can, claims Kawasaki, actually predict when traction conditions are about to become unfavorable and act before slippage exceeds the range for optimal traction. What that means in the real world is hard to predict, but it certainly promises to be a monumental breakthrough in streetbike technology.

To choose the desired degree of traction control, you first select one of the three Power Modes. Mode “F” (Full) places no limits whatsoever on engine power; Mode “M” (Medium) only allows 75 percent of available power—although depending upon throttle position and rpm, full power can be temporarily accessed; and Mode L (Low) limits output to between 50 and 60 percent of full power.

After you select a Power Mode, you then choose a level of traction control. Level 1 is best suited for dry surfaces, either on a racetrack or twisty backroads; Level 2 ranges from twisty, dry backroads to dry city streets to damp surfaces on a race circuit; and Level 3 spans from dry city streets and roads to wet racetracks and wet city streets. That’s 9 possible combinations of power delivery and traction control, all chosen by a single rocker on the left handlebar switchpod, with the selections displayed in the LCD segment of the digital : panel.

There are, however, no adjustments for the ABS system, the acronym for which is KIBS (Kawasaki Intelligent anti-lock Brake System). But as with the traction control, KIBS employs data from more sources than does any other motorcycle braking system; and in doing so, it qualifies the ZX-10R as the first motorcycle on which the fuel-injection/ ignition ECU and the ABS ECU communicate with each other. The system thus responds not just to input from wheel-speed sensors and hydraulic pressure in the

front calipers, it also considers engine rpm, gear position, throttle position and clutch actuation.

At the heart of KIBS is the world’s smallest and lightest ABS control module. Designed by Bosch specifically for motorcycles, the module is 45 percent smaller in volume and 27 ounces lighter than previous units used on Kawasakis. And rather than working at a rate of 5 cycles per millisecond as on other of the company’s ABS systems, KIBS’ reaction rate is an astonishing 100 cycles per millisecond.

According to Taylor, the result is smooth, virtually seamless feedback when ABS is active. There is no perceptible pulsing at the lever or pedal, and braking distances are shortened because the drops in caliper pressure while the system is cycling are much smaller and far more frequent.

Okay, enough of the electronics; what about the mechanicals, like the engine, chassis and suspension? Plenty to talk about there, too.

In essence, the engine is all-new, even if it does contain a few carryover pieces from 2010. For starters, the location of the two transmission shafts has been reversed, with the input shaft and its attendant clutch now stacked on top of the output shaft. This raises the engine’s center of gravity and increases the bike’s mass centralization for more nimble handling. Plus, the tranny now is a cassette type that allows easy access for quick gear-ratio changes. Taylor had not yet received any information from the factory about optional gearsets but felt that such packages would likely be available for racing purposes.

In the power-producing part of the ZX-10’s 998cc engine, the bore and stroke are still at 76.0 and 55.0mm, respectively, but with lighter, shorterskirt pistons that run in cylinders offset 2mm toward the front. This helps reduce the lateral pressure on the pistons and marginally increases torque output. For better durability, the connecting rods were beefed up with thin ribs near the big end, but they only weigh a mere 0.7 ounces more than before.

Lots of new in the valvetrain, as well. The exhaust valves remain unchanged for 2011, but the intakes are 1mm larger, and the ports for both have revised shapes. Valve lift was increased by 0.6mm for intakes and exhausts, which, along with a slight reduction in valve overlap, helps boost torque in the middle rpm ranges. The cams are lighter and harder, now made of a chrome-moly steel derivative instead of cast iron, and their lobes undergo a thorough lapping treatment to provide an ultra-smooth contact surface. In addition, the bucket-style tappets were increased in diameter from 26.5 to 29mm to help withstand the loads of higher valve-spring rates.

Like the camshafts, so too is the crankshaft now made of a harder material. This increases the strength of the journals and also results in more-durable teeth on the integral, machined-on gears that spin the primary drive and the new-for-2011 single-shaft counterbalancer. So much has that small balancer affected engine smoothness, says Taylor, that it allowed the mass of the vibration-calming weights on the ends of the handlebars to be reduced.

Speaking of the primary, it now has a deeper, 1.681:1 ratio instead of 1.611:1, while the final drive is taller (2.294:1 vs. 2.412:1), and the fourth-, fifthand sixth-gear ratios are more closely spaced. Don’t try to do the math; the factory’s intent here, says Taylor, is to reduce the amount of rearend squat and lift during hard acceleration and deceleration at higher speeds, which, in turn, allows more latitude with suspension settings. Seems like a benefit that might be perceived only on a racetrack by an experienced rider, but that evidently is the direction in which Kawasaki is aiming this model.

Improvements in the intake and exhaust tracts are likely to be felt by anyone, however. The ram-air inlet in the fairing has been reshaped and moved closer to the front, while the redesigned airbox is taller above the velocity stacks for easier air entry. A larger filter element has 48 percent greater area, further improving the flow of air to throttle-bodies that have had their bores enlarged from 43 to 47mm.

The exhaust header, meanwhile, is constructed of heat-resistant titanium alloy for greater durability, and it uses tube diameters and lengths that allegedly are about the same as those on pipes tuned for racing. This makes it easier to gain additional track performance by simply installing an aftermarket slip-on. The header’s hydroformed collectors feed a large-volume pre-chamber that includes two catalyzers and an exhaust power valve, capped off by a small stainless silencer with a nearly straight-through internal design.

That short, low-exit muffler contributes to the ZX-10R’s intense focus on mass centraliza tion. So does the all-new twinspar frame and horizontal under-seat shock location that allowed room for the large pre-chamber. The cast-aluminum main frame provides a more direct link from steering head to swingarm pivot, a critical factor in chassis integrity, while the reversed transmission shafts have permitted the new, lighter swingarm also to be shorter.

And if the pre-chamber is removed, the wheelbase can be shortened by as much as 16mm (5/8-inch) for racing use.

Up front, revised geometry involves

“The traction control can actually predict when traction conditions are about to become unfavorable and act before slippage exceeds the range for optimal traction.”

a steering-head angle that Taylor says is “about one degree steeper, with slightly less trail”—his vagueness necessitated by yet more design elements that have not been finalized. The seat now is 10mm lower, and as the bike is delivered, the footpegs are 5mm lower and 2mm farther forward than on the 2010 ZX-10R. The pegs are adjustable, as well, and can be dropped 15mm just by moving two bolts per peg assembly.

Other changes abound, including a 43mm Big Piston fork, a smaller rear brake caliper, a tinier and 20 percent lighter injection ECU that’s now mounted inside the airbox, and all-new styling with crisper lines and sharper angles. The fairing’s critical shapes and vents were designed largely through Kawasaki’s Computational Fluid Dynamics computer program that simulates more airflow and heat-management situations than is possible in an actual wind tunnel.

So, from a visual and specification standpoint, the 2011 ZX-10R shapes up as quite an impressive package, a literclass repli-racer that’s barely bigger than Kawasaki’s own ZX-6R. But although rumors of this machine reaching the 200hp mark continue to swirl throughout the industry, Taylor once again downplays the peak power issue. “The focus has been more on the midrange than on coming up with the biggest horsepower number,” he said. “And if you combine that with the amazing capabilities of the traction control, you can see what we mean by more usable power.”

To illustrate that point, Taylor showed us a pair of computer screenshots taken at Kawasaki’s test track in Japan. Through the use of on-bike data aquisition, the photos compare the throttle positions of a 2010 ZX-10R and the 2011 model all around the track while a test rider rode the fastest lap he could manage on each bike. The photo of the 2011 bike’s best lap shows the rider using full throttle sooner and longer everywhere, even running wide-open in places where he could not on the 2010 bike.

When asked if Kawasaki’s development of the ’ 11 10R was spurred on by the S1000RR, BMW’s auspicious entry into the superbike arena, Taylor thought not. “BMW raised the bar for everyone,” he said, “but this ZX-1 OR has been in development for a long time, well before the BMW came along. It’s always easy to give a bike more power; but if you’re going to put real racing technology in the hands of the public, every bit of it must be very highly refined. That’s what we’ve been doing with this bike.”

We can’t wait to experience the results for ourselves. □

cycleworld.com/201 1 ZX-1 OR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotor. Cycle.

November 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupBuell Fights Back

November 2010 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Triple Threat

November 2010 By Jeff Robert -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

November 2010 -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World

November 2010 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupHeadbanger

November 2010 By Bruno Deprato