SERVICE

A clankity-clanker

PAUL DEAN

Q I own a well-maintained 2003 Kawasaki ZZR1200 with 12,000 miles on it. I bought it new and have never abused it. So, why do I manage to get this bike into what I guess you would call a “false neutral” or “in between gears”?

I wear proper hard-soled riding boots, but I still often get the transmission stuck between gears, and it makes a “clankityclank” noise that sounds like it’s not properly engaged (which of course it isn’t). If I pull in the clutch and fish around with the shifter, I might get it engaged. But if I don’t and hear the clankity-clank noise again, I’ll shut the bike down (for fear of doing any damage), pump the clutch a few times and I’m on my way.

At first, I thought this might be a characteristic of the bike, but I bought a 2007 Triumph Scrambler as a second bike, and this problem happens on it, too. I’m not familiar with how bike transmissions work, so please tell me why this happens, how it can be avoided and if the clankityclank noise is doing damage. It must be me, right? Andrew Baur

New York, New York

A I hate to tell you this, Andrew, but I think you're right: It probably is you. As I was reading your letter, I began thinking about the various shift-mechanism glitches your Kawasaki might be having; but when you said you’re also experiencing the very same symptoms with your Triumph, and that you sometimes “fish around with the shifter” and “pump the clutch a few times” with the engine turned off, that told me what I needed to know: You’re shifting too slowly and too gently.

Motorcycle transmissions are entirely different than car transmissions, in design and in the preferred method of shifting them. With either type, every shift requires two gears moving at different speeds to have their speeds equalized as they engage each other. Car transmissions have synchronizer rings that use friction to, er, “synchronize” the speeds of gears as they engage; those trannies respond well to shifts made comparatively slowly, giving the synchronizers time to do their job. Motorcycle transmissions, however, shift through the meshing of gear dogs, which are peg-like protrusions on the sides of gears and that change ratios by engaging with similar protrusions or matching holes on adjacent gears. This type of gearbox reacts most favorably to quick, firm shifts so the mating dogs can engage each other almost instantly. But if you shift slowly and delicately, the dogs tend to bang and skip off one another as they meet, creating the clankity-clank noise you describe. They also often reject each other, putting the gearbox in a false neutral between gears and potentially bending the shift forks that slide the gears from side to side.

I have observed this same shifting disorder with quite a few other riders, and when I’ve told them to shift much more quickly, they at first thought such a technique would damage their transmissions. But after they tried it and became adept at it-which usually required very little riding time-they realized it was their previous shifting style that had been harmful to their transmissions and that gearchanges on their bikes had become smoother than ever before. So, stop shifter-fishing and clutch-pumping and begin making quick, deliberate shifts. You’ll like it-and so will both of your transmissions.

This one's a clunker

Q I have an '07 Kawasaki Vulcan 1600 Classic with about 3000 miles on the clock. I bought it new and love it dearly but I’m worried that it might have a long-term health problem. The transmission makes a really loud clunk on the 1-2 shift. It has done this from the get-go. I’ve tried lots o’ stuff-shift fast, shift slow, shift at low rpm, shift at higher rpm, preload the shifter before pulling the clutch-but alas, the same results: a really big clunk. I commute in city traffic, so I spend a lot of time shifting. Is this normal or am I setting the bike up for an appointment with a transmission surgeon?

Bill Browne

Rio Rancho, New Mexico

A In all likelihood, there is nothing wrong with your Vulcan's gearbox.

All of Kawasaki’s big cruisers tend to make a clunking noise during the first-tosecond shift, as do the gearboxes on many other large-displacement V-Twin cruisers. These bikes generally have a large ratio gap between first and second, so there is a considerable difference in the speeds of the engaging gears as they come in contact with each other. What’s more, big VTwins produce large torque pulses that are delivered only twice every 720 crankshaft degrees and at uneven intervals. So for durability, their transmission gears tend to be rather large and heavy-much more so than those in, say, a typical lOOOcc inline-Four, which makes more horsepower but a lot less torque delivered four times every 720 degrees at even intervals. When two gears spinning at considerably different speeds engage, one of them has to match the speed of the other almost instantly; if those gears are heavy, as they are in the aforementioned big V-Twins, that engagement results in a distinct “clunk.” Many of these same bikes also emit similar sounds during shifts between other gears; but those gears are smaller, lighter and not subject to such large speed differentials (the ratio drops between them are smaller), so the clunks are not as loud.

Father knows best

Q I recently helped a friend and his dad put new tires on his bike in their home garage. When I grabbed a wrench and started to loosen the rear axle, his dad stopped me and said I was using the wrong end. It was a 24mm wrench with open-end jaws at one end and a box wrench at the other. I had tried to loosen the nut with the open end, but he said I shouldn’t do that because the jaws can spread easily and allow the wrench to slip. He said I instead should use the box end. Is he correct or just being very cautious? It seems to me that a 24mm wrench is a 24mm wrench, no matter what type it might be, and I can’t imagine the jaws on a wrench that big flexing enough to slip. Justin Leonard Baton Rouge, Louisiana

A Your friend’s dad is correct in telling you to use the other end of the wrench, but not for the reason he expressed; unless an open-end wrench is of very poor quality, jaw spreading is not a major concern.

A box-end wrench or a socket always is preferable to an open-end wrench except when neither can be slipped around the fastener-such as when the hex is on a hydraulic line or a turnbuckle or located so close to something else that only an open end will fit. With an open-end wrench, the jaws only make meaningful contact with two of a hex’s six comers, and that contact occurs right at the very edge of the comers. The accompanying illustration shows this contact, though the clearance between the wrench’s jaws and the fastener’s hex on these drawings has been slightly exaggerated for the purpose of clarity. If the force required to turn the fastener exceeds the strength of the small amount of metal right at those two comers, the wrench will slip and round off the comers. A box-end wrench or a socket, however, makes contact with all six of a hex’s comers, so they theoretically are three times less likely to slip and round off those comers.

Wait: There’s more.

A basic six-point box

wrench or socket is, in essence, just a simple inverse hex, with six sharp internal comers to match a fastener’s six sharp external corners. Even a basic 12-point wrench has sharp intersections in all 12 of its corners. This means that when a sixor 12-point box-end wrench or socket tightens a hex, it applies pressure right at the very edges of the fastener’s six corners. Normally, this is not a problem; but if the fastener is well-used or has less than perfectly sharp corners, the wrench or socket can slip and round off the comers altogether.

I used the word “basic” in describing the aforementioned wrenches becausek there is a more-effective type. About 50 years ago, Snap-on addressed the problem of rounded-off fastener comers by patenting what it called Flank Drive. This involved putting a small relief at each internal comer of a box wrench or socket (either sixor 12-point) so the force of turning would be placed not at the very comer of the fastener but rather a short distance from it, on the hex’s flank, hence the name. This allowed more of the hex’s metal to resist the force of turning, making it less likely for the comers to be rounded off. In fact, Flank Drive was so effective that a wrench with that design often was able to loosen nuts and bolts that already had been rounded off.

Snap-on’s patent expired years ago, so most reputable tool manufacturers now use some form of flank drive on their box wrenches and sockets. Snap-on even has developed Flank Drive Plus for openend wrenches. This design uses special notches on the wrench’s jaws that apply the turning force a short distance from a fastener’s comers rather than right on the comers’ edges. Flank Drive Plus open-end wrenches are an improvement over the standard type, but because they still only contact the fastener on two comers, they are not as effective as box-end wrenches.

Air apparent

Q I recently changed the hydraulic clutch fluid on my Honda ST 1300. I have done so every other year with clutch and brakes. This time, the bike had not been ridden for a few months and the clutch wasn't functioning. It felt like it had air in the system and apparently did, since after I changed the fluid, the clutch worked fine. How would air get in this closed sys tem if fluid hadn't leaked out? I've never had to add fluid to either the clutch or brake resevoirs except when changing it, and it's never been low. There was a small amount of particulate in the first little bit of fluid >

that I pulled from the bleeder, but after that, I only got fluid. David Maurer

Posted on America Online

I know nothing about the conditions under which your Honda was stored or last ridden, and neither did you tell me if the bike was started or ridden after it was taken out of storage. So all I can do is offer a semi-educated guess and suggest that most likely, a small amount of moisture in the form of condensation accumulated in the system while the bike was in storage and then was turned to vapor when the engine was started and run. You may not have detected any air in the system while exchanging the old fluid for new; but even a tiny amount of air in a motorcycle’s small-volume hydraulic clutch system can give the lever a spongy feel and cause the clutch to operate lethargically.

Boots are made for rotting

Q On my 2002 Harley-Davidson FLHTC Classic, the rubber boots that cover the lower half of its Showa shocks have rotted out. I thought this would be an easy find at my dealer, but that’s not so; seems all they want to do is sell me a new set of shocks at the cost of my firstborn child! If you could please point me in any direction as far as replacements are concerned, I would really appreciate it. Howard W. Fritkze Jr.

Lockport, New York

A Lots of other FL-series riders have experienced this same problem. Because replacement boots are not available from Harley, some of those riders have anted up for aftermarket shocks, many of which work better than the Stockers anyway. But riders who preferred to stick with OE units found a fairly easy and inexpensive solution: used FL shocks or

rubber covers. There are hundreds, maybe even thousands of these shocks floating around in H-D dealerships, independent repairs shops, people’s home garages and on the Internet, all of them having been replaced with something else. Some were removed because their rubber covers had deteriorated, but others were simply swapped-sometimes in brand-new or likenew condition-for aftermarket shocks, and they all have been languishing in a box or on a shelf ever since. Their owners would probably be glad to part with the shocks, or perhaps just the rubber covers, for a small fraction of their original cost.

So, ask around at local independent repair shops and H-D get-togethers. Do a search on eBay. Put a “Want to buy” listing on craigslist. A perfectly good set of used rubber covers is out there with your name on it, and finding it should not be too difficult. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Lost Von Dutch

September 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThis Is Your Brain On Motorcycles

September 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOld World Craftsman

September 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2009 -

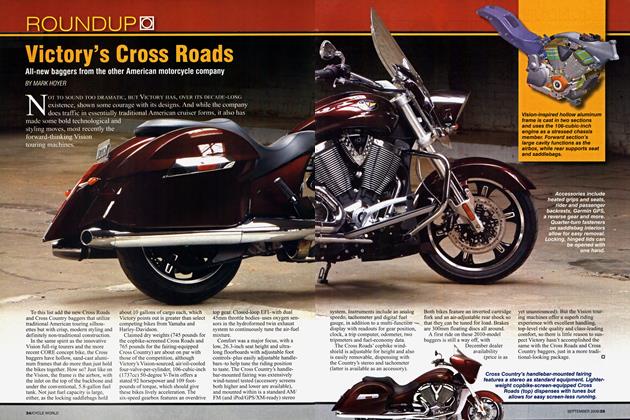

Roundup

RoundupVictory's Cross Roads

September 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1984

September 2009 By Blake Conner