FLIGHT RED

Harley-Davidson's past, saved for the future, one story at a time

PETER EGAN

DESPITE WHAT AWED BYSTANDERS MIGHT think, that's not a real Harley tattoo on the back of my left hand. It's just a "bar & shield" stamp I got at the gates of the new Harley-Davidson Museum yesterday. If I washed a little more often, it would be gone by now.

Yes, a mere six months after this huge new museum opened, I finally made the 75-mile drive to Milwaukee just this week. Why the delay? Well, there's "opening night phobia." I always wait to see popular movies until a few weeks after they've opened, when the popcorn line isn't so long. Unless they have motorcycles or WWII airplanes in them. Then I have to go right away.

The other factor is cabin fever. Here in Wisconsin, making a pilgrimage to admire stationary motor cycles always seems like a better idea when it's about 2 below zero, as it is right now.

So my buddy Rob Himmelmann-who is also about to go nuts from winter hibernation-organized a little class field trip yesterday, and four of us jumped in a car and ran over to Milwaukee.

The museum is in the heart of the old downtown, a modern indus trial-themed structure of brushed steel, galvanized duct ing and glass, right along the Milwaukee River-complete with tugboats and coal barges going by.

We bought our $16 tickets, hung up our puffy arctic coats and were met at the turnstile by Bill Rodencal, an old friend who runs the museum's restoration department. Bill introduced us to a gentleman named Jim Fricke, who designed the museum's many displays.

A couple of years ago, pre museum, when Bill gave us a tour of Harley's archives, all of the collected bikes were stored cheek-by-jowl on the restricted-access fourth floor of the old brick factory at 3700 West Juneau Avenue. I'd imagined that the new museum would simply spread them all out for more viewing space, but this isn't the case. Instead, a much more imaginative iayout has been adopt ed. Fricke reasoned that people don't really need to see four or five similar bikes rrom the same year. Instead they need context-one or two bikes from a given era, surrounded by the posters, riding gear, letters, photo graphs and touch-screen films that typify the period. As a result, only 138 motorcycles are on display to the public at any given time, and another 459 are stored in stacks of alumi num fork-lift pallets, where they can easily be rotated into the museum from time to time.

"People don't need to see four or five similar bikes from the same year. Instead, they need context-one or two bikes from a given era, surrounded by the posters, riding gear, letters, photo graphs and touch screen films that typify the period"

Besides the motorcycle and cultural displays, there's an "Engine Room" showing all the generations of Harley engines, complete with exploded-view films and hands on displays. One of my favorite places, however, was the "Experience Gallery" at the end of the tour, where you can sit on a wide variety of new and vintage Harleys and watch

of my favorite places was the Experience Gallery, where you can sit on a wide variety of new and vintage Harleys. All museums need a room like this."

wall-sized films and photographs of the American landscape go by. Naturally, I sat on their black XLCR Café Racer, exactly like my own. Felt good. All museums need a room like this.

We had lunch in the museum restaurant (I had the sausage and sauerkraut platter, which only seemed right in the Germanic heart of downtown Milwaukee), then Bill showed us the new restoration shop. A J L1.-~ 1A.~-.

And there, standing on a bike lift, was Bill's current proj ect, an unrestored 45 flathead Twin, a 1941 WLD, in its original "Flight Red" paint scheme.

Bill told us the strange story of this particular bike, and I realized that sometimes a single anecdotal tale can tell you more than a shelf full of motorcycle history books.

The WLD was originally purchased as a high school graduation present for a young man named Wallace Van Sandt, from Birmingham, Alabama. He rode the wheels off his bike-visiting girlfriends all over the South and putting nearly 19,000 miles on the odometer. He then joined the Army Air Corps and became a tail gunner on a B-17.

The bomber, "High Pointer," was heavily hit with anti-air craft fire while bombing the rail yards in Budapest, Hungary, in 1944 and tried to make it to the Adriatic on two engines, but was hit again by German 88s in Yugoslavia and came down within sight of the Adriatic, unfortunately just behind German lines. It went into a flat spin and some of the crew bailed out but the centrifugal force of the spin apparently pre vented Van Sandt from escaping. He was buried in Yugoslavia by sympathetic partisan guerillas, and his remains were finally recovered and sent home several years later.

His bereaved mother, Lila, kept the Harley, untouched, for the rest of her life. She built a small stone building in her backyard as a shrine and kept everything Wallace owned-his clothes, track jersey, boyhood possessions, the letters home and all the personal effects and uniforms that were sent back in a duffel bag by the War Department. The life of an adventurous young man, gone at 22, symbolized in the things he owned.

When Lila became terminally ill in 1964, she gave these artifacts to a nephew named Cleve Porter. He kept them all these years-and even rode the Harley for a few hundred miles in college. Recently, at the age of 68, he tried to donate everything to a military museum, but they were interested in only part of the collection. He wanted to keep it all together and was fortunately contacted by Bill at the Harley Museum, where the full meaning of his collection was appreciated.

Bill plans to do only a light clean-up on the bike, removing some of the dust and patina of long storage. Otherwise, the 45 will remain exactly as it looked in old family photographs of Wallace astride his bike in 1942. Same sawed-off muffler, same dents and scratches in the pipes.

"We're going to put it all together in a display and bring it out for Memorial Day," Bill told me.

Somehow it all fits together: Harleys, radial aircraft engines, olive-drab B-17s, flying and riding and a bright splash of color and freedom in a summer before going off to war.

You look at that red Harley, the miles on the odometer and the photos of the youthful bomber crew and you almost don't have to read Wallace's letters home to understand who he was. He's like someone you already know.

And I guess this is where the real museum is found, and Bill and Jim were trying to show us, the light and heat within that lovely new structure of glass and steel.

"His bereaved mother kept the WLD Harley, untouched, for the rest of her life, She built a small stone building in her backyard as a shrine"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

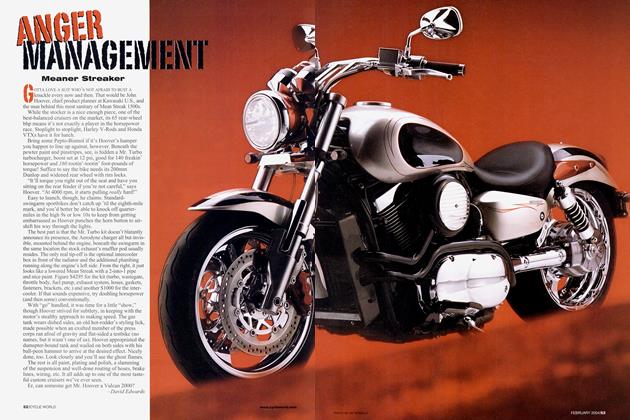

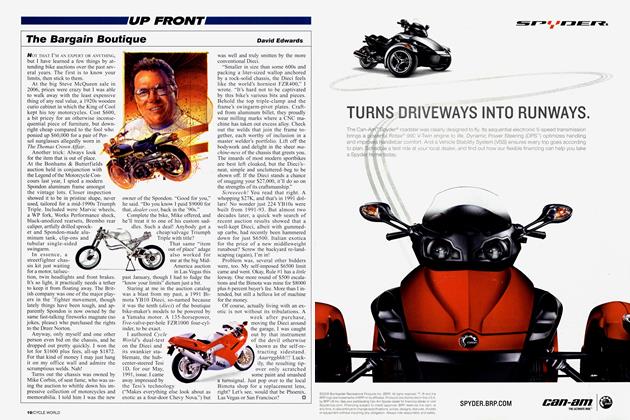

Up FrontThe Bargain Boutique

June 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsClimate Control

June 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMpg Economics

June 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupBmw's Superbike Hits the Street

June 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago June 1984

June 2009 By Matthew Miles