MOVING FORWARD

RACE WATCH

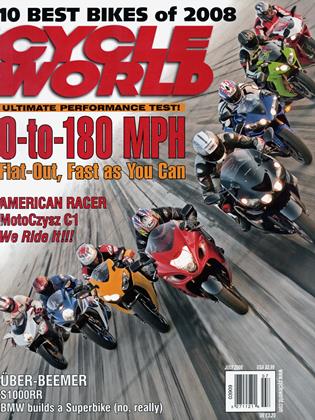

What began as a series of unique concepts is now a potent prototype. We ride the latest MotoCzysz C1.

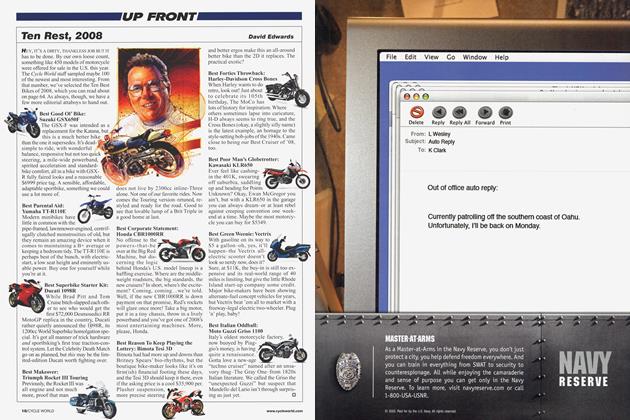

NICK IENATSCH

THIS PAST JANUARY, I COMPLETED A TOTAL OF 10 laps at Las Vegas Motor Speedway on a pair of MotoCzysz C1 prototypes. I further witnessed a test rider from the small Oregon-based outfit start and finish an additional 70 laps on the same two machines. From both seat and sideline, the experience was impressive, particularly when you consider that I was present during the project's early days, when the "proof-of-concept" test mule wouldn't idle, wouldn't rev and struggled to even run. Forget lasting 10 laps. But teething problems begat solutions, power grew, the sound matured and dyno runs became lap times.

That both MotoCzysz prototypes were running at the end of the two-day Vegas test was progress. To established manu facturers, that might not seem like much of an achievement. But for a fledgling start-up like MotoCzysz, completing such a test with both bikes still running strong was huge.

I flew home and typed my impressions, comparing the lat est prototypes to the early mule-the one that made three laps before the clutch expired, the one that struggled to start, the one that ran but not well. In nine short months, MotoCzysz had made real headway, and my story reflected how enjoyable the most recent examples were to ride. They weren't record setters, but they were rideable and hung together.

That story was put on hold when the C1's creator, Michael Czysz, phoned CW Editor-in-Chief David Edwards and asked for a one-month reprieve. He said the en gine team was nearly done with an up dated-spec powerplant boasting serious improvements. Edwards agreed to hold my story-it turned out to be a two-month delay. Now, having ridden the latest ver sion of the bike, I believe he made the right decision.

"The prototypes you rode in January were restricted to 12,500 rpm and made less than 150 horsepower," Czysz ex plained. "The engine losses were high and combustion efficiency was low. We oversized all the plain bearings and in creased oil flow in an effort to minimize and reduce friction, but we miscalculat ed. The excessive oil circulating in the engine actually added to its parasitic loss es. Now, besides reducing friction, we have increased combustion efficiency. The larg est power gains in the latest C1 came pri marily from a redesign of the intake port and combustion chamber, which allowed us to further reduce ignition timing."

Czysz designed the 990cc engine to spin to 16,000 rpm. On the dyno, the team's most recent work resulted in rou tine readings of 200 crank hp at 14,500 rpm. Because so much was riding on my next track test, the team was conservative on the dyno in hopes of ensuring a bul letproof March outing in Vegas. Bench testing went smoothly with the excep tion of a cracked weld in the sump's stainless-steel windage tray, resulting in engine damage sufficient to necessitate a full rebuild. Related damage to the gear that mates the crank with the torque tube went undetected and would later come back to haunt the team in Vegas.

The C1 wears an electronic "gripper" clutch-programming determines when the plates regain traction-that for my second ride was unplugged to eliminate any bandaid effect on off-throttle fueling. Czysz must have warned me 100 times to pay special attention to corner entrances; en gine braking could cause rear-wheel chat ter when the bike was rushed into cor ners. I've felt pressure before to not crash expensive bikes, but the look in Czysz's eyes was the same one I'd seen in the eyes of a father on prom night. And I don't mean my father.

Remote starter in place, the engine fired immediately and settled into a fast, radical and loud idle. Both Czysz and his crew seemed at ease, rejuvenated even, as though they knew they'd turned a cor ner. I slipped onto what felt like a slight ly oversized 250cc GP bike. The seat was firm, gas tank narrow, bars perfectly set for my 5-foot-8 frame. Weaving back and forth along pit road didn't produce the overly quick, ultra-light steering I expect ed. Instead, it felt more linear than a modern 600cc racer-replica -tight, plant ed, stable and, well, race-able. Steering geometry is an intriguing mix of steep rake and long trail (Czysz refused my re quest for specifics): each can be indepen dently adjusted in minutes. Wheelbase is 55.9 inches.

As I scrubbed the 16.5-inch Michelins, I noticed that the sculpted saddle was a bit restrictive~ a simple rounded pad would have suited me better. Clutch pull was improved, with effort now production-bike light. Brembo brakes provided their usual perfection, and the throttle was a 100-degree turn with good feel. I had watched the / MotoCzysz test rider puli the /.~. trigger exiting slower corners, and I was itching to expe rience what appeared to be impressive acceleration. Soast apexed onto the back straight and began to pick up the bike, I snuck the throt tle to the stop in second gear.

Folks, we've really got something here. The counter-rotating in line-Four spun up quickly without a hint of vibra tion or roughness. tag ging the rev-limiter soon er than I expected. Third gear continued the rush, and I engaged fourth at full throttle with help from the electron ic ignition-interrupt. The C 1 surged forward to a soundtrack the world has never heard but won't soon forget. It was the same addictive, vel vety smooth power deliv ery I `ye experienced on Mo to(iP bikes, a delivery that can't be matched by even the best pro duction bikes. As I squeezed on the brakes for the rapidly ap proaching corner, an expletive of surprise burst from my lips. I realized that Czysz's vision to produce an Anieri call sportbike capable of competing with the best from Asia and Europe was a real possibility.

Make 110 mistake. i'm not saying the C1 makes MotoGP-level power. Right now, it makes liter-sized sportbike pow er and that ain't bad. The CI didn't blur lily ViSion and fuzz my brain like Troy Bayliss' 990cc Ducati Desmosedici did; I could actually think and breathe while accelerating on the C 1. What 1 a/n saying is that the C1 produces its power in the same light, effortless, free-revving style, making it abundantly clear that this team now has the basis for combus tion correct. MotoCzysz can now experiment with cam profile and timing, piston-dome and cylinder head shape, firing order and igni lion timing. And don't forget, when I rode tile bike, tile soft rev-lim iter was set at 13,200 rpm; the eflgilleers have another 3000 rpm to exploit.

Remember that .. damaged gear ` that went tindetected? After two laps, it couldn't take any more stress and spit a tooth through the crankcase. When my oiled-up boot slipped off the footpeg, I returned to the pits ecstatic with the engine's power but concerned about the failure. The bike was done for the day, but a call to Portland put an engineer N on a plane to Vegas with r the necessary parts. -. Czysz showed me the failed gear. "That was the only problem," he said. "You should plan to ride it again tomorrow. So, what did you think of the bike?"

Both Czysz and 1 raced 250s at a national level in the 1990s, and we both own and ride modern sportbikes. When he asked what I thought of his motorcycle, his question was based on our knowledge of how well a bike can work when it's right. The C1 may one day be considered a monumental motorcycle, but at the moment there are things about it that / j still aren't right.

J Too much closed-throttle ac celeration, for example. Read that again. The electronic throttle j can be adjusted to add fuel at closed throttle to prevent rear-tire chatter upon corner entry. Yes, the gripper clutch would help / here, but the team needed to get the e-throttle setting right. It wasn't, and the over-fueling tried to push the bike into corners while I was busy braking. Fortunately, the system is infinitely ad justable. Electronics engineer David Sprin kle was taking notes as I spoke.

The next problem is common as pow er increases: The chassis needed improved damping. Czysz had already seen the need to slow rebound at the rear as he watched me enter corners. "Finally, we get to start adjusting the chassis," he said, smiling. "We've been working so hard on the en gine. Now that the bike is on track, we can start tuning the suspension."

When I left the track that night, Czysz's tireless father, Terry, also a motorcycle racer, and lead mechanic Quentin Wil son had the bike torn down, its quickchange tranny removed, and were wait ing on the flight from Portland. I saw con fidence in their faces. It was a confidence that hadn't always been there during Mo toCzysz's short, two-year existence. A previously damaged part had failed, but finally the basics of this patented engine were right.

Czysz once told me that his job would have been 90 percent easier if he had sim ply purchased an existing engine and de signed a chassis around it. Solving cool ing roblems, balancing cranks, design ing oil pumps, sizing bearings, choosing cam lift and profile... Does your head hurt yet? Czysz and his team have designed and developed more than 2000 parts. Ninety-nine percent of the C1 consists of custom, one-off pieces.

How difficult has this mountain been to climb? The only American start-ups that have survived since Harley-David son are Victory and, with Harley's help, Buell. Two companies in 105 years. Four time 500cc World Champion Eddie Law son has provided insight and enthusiasm along the way. "Most modern sportbikes are all the same," he told Czysz. "Inline Fours. Double overhead cams. Four valves. Fork and single shock. All anyone does

is tweak existing technology."

Taking Lawson's comments to heart, Czysz started in 2005 with a clean sheet of paper. Expensive patents followed and a bike emerged. CW's Mark Hoyer and I were dispatched to Portland, and readers were informed of someone who was do ing something different ("Secret Superbike," January `05). Not different for the sake of difference, but different for the sake of performance.

Sportbikes wheelie too readily. You should be able to change steering geom etry and transmission ratios quickly and easily. Conventional forks have stiction (static friction) under braking and cor nering loads. Engines are too wide. The list goes on and on. Most of us enjoy bikes as they come from their respective factories. Czysz thought sportbikes should be better, and he undertook a massive effort to prove it.

"If the process were easy, there would be 40 American manufacturers," he said. "But there's nothing easy about it. De signing a bike that can come close to the products put out by the Japanese and Ital ians is tougher than you can imagine. Sad reality for us is, this is not so much an en gineering problem as it is a finance prob lem. If we don't succeed, it will probably be because I could not finance the com pany, not because we couldn't build the bike."

Czysz's confidence in his concepts has been unfailing, yet he remains open to ad justments and improvements to the orig inal designs. The longitudinally mounted inline-Four now has every other cylinder splayed 15 degrees, allowing arrow straight vertical intake tracts and a sin gle intake cam for all four cylinders. Firmg-order experiments yielded a 15-per cent power gain. Linear fork bearings were replaced with floating, recirculating bear ings. Twin clutches became a single unit.

Through all these challenges (and many more), the team has ridden an emotional rollercoaster from the heights of Mount Everest to the depths of the Pacific Ocean, often in a matter of hours.

Next day, engine rebuild complete, I'm up to speed by the third turn. Sprinide got the closed-throttle mapping right, and increased rebound and compression damp ing added chassis stability. Most cornerexit problems are caused by corner-entry problems, so with the C1 performing bet ter at entry, exits improved greatly. For mer GP rider Jeremy McWilliams has raced more exotic machinerythan I'll ever see, and his take following a test of the C1 at Miller Motorsports Park last year hinted at how nicely this bike is to ride into a corner. "It's the best-turning bike I've ever ridden," he enthused.

Czysz must balance a desire to revolu tionize motorcycle design while retain ing all the touchstones that current riders need, basics such as control placement but also "feel" items like weight transfer and traction communication. Czysz believes that the frame should be rigid and flexfree, While the fork and swingarm should be engineered (and adjustable) for flex. As I picked up the pace, I searched in ear nest for traction information that would allow me to continue lapping scratch-free.

That search began at the clip-ons. The Brembo Monoblocs and front Michelin slick are proven components, but the trans parent performance of these trustworthy pieces is matched by the MotoCzysz sin gle-shock front end. As noted, Czysz em ploys recirculating bearings in the fork sliders and a single Ohlins-built coilover damper to produce the suspension necessary without unwanted stiction un der braking. Much of the world resorts to larger fork tubes and simply lives with the stiction and compromise, but as loads rise and lap times drop, those compro mises increase.

I don't have the riding skills to run at MotoGP pace, but Czysz's front end was communicative and trustworthy no mat ter if I was trail-braking, turning the bike quickly or bending it in slowly. There were no surprises and, most importantly, no quirks.

Adjustable lateral flex is part of the MotoCzysz fork design, and while I'm not fast enough to need those adjustments, keep in mind that if you're one second off the pace at the world level, you'll start from the fourth or fifth row. All the ad justability built into this bike-and the ease with which those adjustments can be madewill pay enormous dividends as the pace escalates. Put simply, a rider will be able to try more options in less time. Racers re alize how big this could be.

Shane Turpin, one of MotoCzysz's test riders, has often commented how quick ly he could go on the first lap due to the bike's inherently good feel. My first fly ing lap was a seriously quick revolution of the Speedway's inside road course, and it got better from there.

I started pulling the trigger pretty hard off corners, and the bike accelerated with no drama-no untoward gyrations, wild spins or confidence-sapping wiggles. It was really hooked up. Dual rear springs allow "regressive" damping that a coilover shock can't provide, and the bike ate up stutter bumps on the course's tightest corner.

I had been asked to shift at 13,200 rpm (test riders would later run to 14,000), 50 I was killing acceleration early. The en gine really started pulling seriously at just under 8000 rpm. On my last lap, I tried to spin the tire in two places and couldn't do it. I tried even harder to wheelie off a pair of second-gear corners and the front end stayed down. Hey, I can wheelie a much slower, much heavier Honda VFR800 off those same corners, so I at tribute the C1 `s longitudinal engine lay out to the bike's reduced desire to wheelie. Add anti-squat geometry in the swing arm-pivot design and you have a bike that drives off corners so controllably that I still have no idea where the limit is.

A huge part of rear grip is not just> power but power delivery. For a nervous rider on a one-off motorcycle, initial ap plication of throttle is important. Produc tion fuel-injection has resulted in "digi tal" on-throttle feel. What I want is the haziness of a carburetor as I begin to open the throttle with the exactness of injec tion everywhere else.

The C1 employs a single Bosch twin cone injector below each throttle plate, a design that allows exact fuel metering for improved idle and on-throttle smooth ness. A cable connects the rider's right hand to two throttle bodies, while a throt tie-position sensor reads the movement demanded by the rider (in ½-degree in crements) and informs the ECU, which in turn operates the remaining two throt tle bodies. This latest C1 prototype ex hibited a "digital" initial throttle but re sponse was on par with a Honda RC5 1 or a CBR1000RR-in other words, not too bad.

I've written about longitudinal wob bles on high-strung bikes brought on by the rider moving too quickly or spinning the tire, but the C1 doesn't exhibit this tendency-at least not at current power levels and lap times. On that day and at that track, I felt nothing that would hold me back from going quicker and quick er. In fact, that's what happened during each of my laps. Had Czysz handed me a bike and said, "This one's going to the crusher so tear it up," I wouldn't have held anything in reserve. But he never said that, so I rode with the modicum of nervousness ajournalist should feel when piloting a $1 million prototype.

The latest C1 must be considered a new beginning for MotoCzysz. Had I pulled a racebike out of my transporter and lapped this quickly right off the bat, I would be ecstatic because the situation would only improve as I became more accustomed to the bike and altered it to fit my needs. To say the C1 is in its in fancy is an understatement. Czysz told me, "I admit that there are certain things we don't know yet, such as optimum valve lift and duration, ideal fuel-injec tor phasing, perfect intake length, ex haust length and diameter, oil flow, etc. But now the basics are right, and the de tailing can begin."

Stick around, this thing is getting good.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue