DUCATIS & CIGARETTES

Some things you quit, others you don’t

PETER EGAN

BACK WHEN I WAS A FULL-TIME TECH Editor at Cycle World during the early Eighties and lurking in the roomy but windowless office now occupied by Editor Edwards, I had a small quote from a British bike magazine taped to my door.

It read, “Ducatis are like cigarettes; you may quit for a while, but you always come back to them in the long run.”

This little gem of wisdom struck a chord with me because both addictions seemed related in some strange way.

I was then trying, with only limited success, to quit smoking and had several times ceremoniously thrown my last pack of Camels (a fine blend of domestic and Turkish tobaccos) into the trash, only to have the urge for a nicotine hit return at the least opportune time. Usually while I was working alone in the office over the weekend.

I’d be sitting there typing my deathless prose about rejetting a Honda 400 Hawk with midrange stumbles when, suddenly, a red message would light up in my brain saying, “Tow must have a cigarette.” And I couldn’t concentrate until I did.

Well, I’ve long since stopped smoking-quit cold turkey on my 50th birthday-but the instinctive urge to own a Ducati has remained as persistent as that old cigarette habit used to be. I’ve owned nine of Borgo Panigale’s finest over the past 28 years, and the occasional gap in ownership has always set off a motorcycle variant of that same red message light: “T?w must have another Ducati.”

The problem goes back quite a few years.

While I admired the small Ducati Singles that hit our shores in the Sixties (even if they weren’t Triumphs), the first stirrings of genuine desire came with the arrival of the exquisite round-case 750 SS V-Twins. These were expensive, however, and seemed virtually unobtainable, as any Ducati dealer lucky enough to get one simply kept it. They were always on display in showroom windows, but I never saw one on the street.

It was the square-case 900SS, built in much larger numbers, that finally made the sleek desmo Twins available to mere mortals.

And it was here that the real addiction took hold.

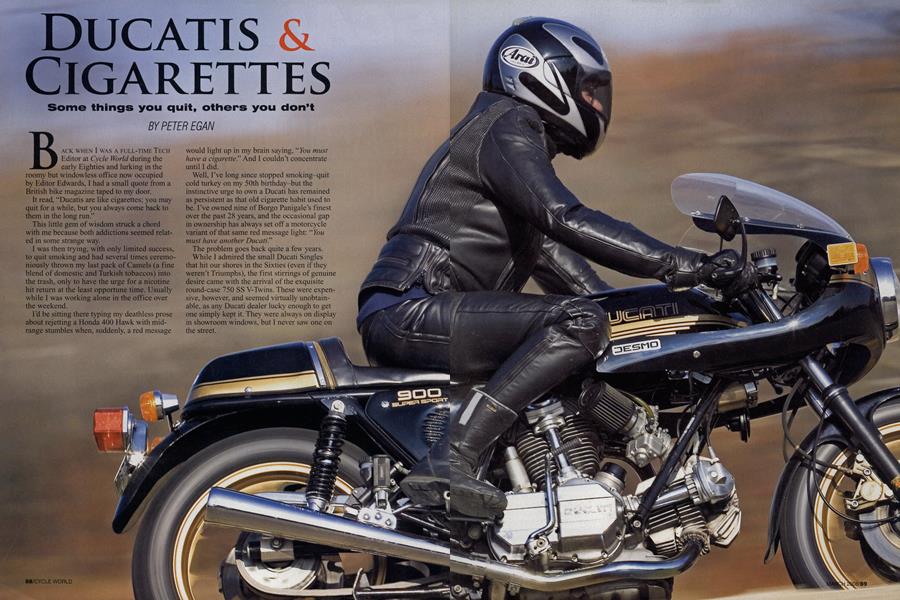

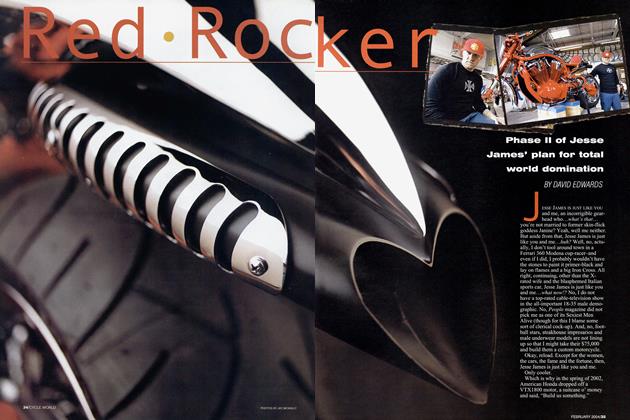

It started about the first week I worked for Cycle World, early in 1980, when I arrived in California from Wisconsin just in time for the Los Angeles Motorcycle Show. A bunch of us rode up there from the office, and when we walked through the doors of the main pavilion, the first thing we encountered was a black-andgold 900SS rotating on a raised round platform under the lights. It looked like a wedding cake with a black widow perched on top.

Except the Ducati was better looking than any deadly arachnid.

Equally dangerous, but much better looking. It had gold wheels, an anodized chain and bodywork in ebony black with discreet gold trim to stir the Anglophilia of those of us who misspent our youths lusting after Vincents, Velocettes and AJS 7Rs.

But this was no dusty old British classic. This was the most potent production track weapon of the moment, its immediate antecedents having recently won (in variously tweaked forms) both the Isle of Man and the Daytona Superbike race. And the bike was cleaning up everywhere in production club racing. Spartan, purposeful and uncluttered.

While the other CW guys wandered off, I stood there transfixed by the beauty and rightness of the design, sort of like Wayne (or was it Garth?) staring at that white Stratocaster in the window of the music shop. Anticipating that movie by a couple of decades, I said aloud, “Oh yes, it shall be mine!”

As luck would have it, a few weeks later I won a $5000 editorial prize from CBS Magazines (which then owned Cycle World) for a story I’d written about my Triumph Bonneville. It was clearly a case of mistaken identity or some bizarre corporate foul-up, but I wasn’t about to ask any questions.

The check arrived at 11:45 on a Friday morning, and at noon I ran down the block to Champion Kawasaki-Ducati and bought a used 1978 900SS from shop owner Lee Fleming. When I signed over the check, the money had been in my hands for exactly 15 minutes.

This bike was a runner. It had been Lee’s personal streetbike, and he was then the AFM Open Production class champ on his racing 900SS. The compression was up slightly and Jerry Branch had reworked the cylinder heads.

I remember my own first ride as being somewhat disorienting. Compared with, say, a Honda CB750F or Suzuki GS1000 of the day, the Ducati was slightly harsh and uncomfortable, with a severe shortage of steering lock. Your feet were tucked up behind you in a full racing crouch, and the exhaust note sounded like Muhammad Ali working a speedbag with forceful, rhythmic deliberation. You looked down at the engine and wondered if it had enough aluminum around the cylinder bores to contain all that violence.

Getting off my Honda 750 and climbing onto the Ducati was like leaving the Hilton and entering a Trappist monastery, a dark place lighted by torches where you slept on a stone floor.

No mini-bar in this room, pal. We’re looking for salvation through austerity.

But out of the crowded city and on the back mountain roads of California, the bike transformed itself. Fast, composed and easy to ride, it clicked smoothly along like a runaway freight train compacted into a highly precise instrument of speed. Pure pleasure, a mechanical drug that seemed to mix some kind of opiate with an equal amount of caffeine.

Nearly every Sunday morning my buddy John Jaeger (on his R90S Beemer) and I would take a ride over the Ortega Highway to Lake Elsinore for breakfast. The road was nearly empty in those days and largely unpatrolled.

Or so we thought. On a long downhill straight coming out of the mountains toward San Juan Capistrano, we got side by side and held our throttles to the stops. We’d just hit an indicated 135 mph when two cop cars materialized out of the rapidly approaching distance and turned on all their lights and sirens. We pulled over, feeling suddenly busted and financially ruined, but the cop cars kept going. I think they were on their way to investigate a minor fender-bender we’d passed earlier and were too busy to turn around.

John and I looked at each other, shrugged and split for home. We spent the rest of the day hiding out in our respective garages, staying away from windows.

After a couple of years, I sold the 900SS to buy something more practical (a category that includes nearly all other objects in the universe), then started twitching like a dope fiend and bought another 900SS in the late Eighties.

Since then, I’ve owned a long string of Ducatis, old and new, including yet another bevel-drive 900SS. I sold that last bike to a friend in Colorado seven years ago and just bought it back last summer. It is now sitting in my garage, and here it will stay.

I guess I’ve finally reached the age where I’m not looking for anything more practical. I have a couple of modern bikes that

work better for normal daily use, but I’ve come to realize that Ducatis are important not just as great machines, but as symbols of a healthy resistance to compromise.

In a world where everything gets dumbed-down, fattenedup or over-civilized, Ducati has managed to keep a focus of purpose-what my friend Jeff Craig calls a “core idea of what they do best.” They don’t try to be all things to all people. Ducati makes racing and sportbikes that are light and charismatic, and that’s it. We don’t want Eric Clapton doing the Best of Justin Timberlake, and we don’t want Ducati making cruisers or 800-pound touring rigs.

Also, if you like Italy and things Italian-which I do, despite being largely Celtic, from a family that was notoriously undemonstrative-Ducatis are a way of celebrating everything distinct about the Italian approach to life, as filtered through a spare-yet-flamboyant mechanical sensibility.

Motorcycles project a cultural force field upon your life, and Ducatis do it better than most.

The bikes have Emilia-Romagna written all over them, and seem to have been made for narrow Apennine roads lined with Lombardi poplars and old stone buildings. Which is why you don’t want to go off the road in that country. And why Ducatis generally don’t have floorboards.

Another key quality in Ducatis is presence. Whether you’re riding along on a 250 Mach 1, an old 900SS or a new 1098, you never forget for one moment what you’re riding. You keep looking down at the tank and instruments and thinking consciously about where you areboth literally and in the flow of history. Remaining oblivious to my 900SS while speeding down the highway would be difficult indeed, like sitting across the dinner table from Hilary Swank and trying to forget who she is, or that Clint Eastwood may have taught her how to box. The mind doesn’t wander much.

But enough of these show-business analogies. Back to smoking.

Like those cigarettes I gave up a decade ago, Ducatis also carry with them a bracing touch of fatalism. The owner has to be somewhat willing to dive into the unknown (or at least be willing to endure a desmo valve adjust) in order to make life more interesting and less predictable. The bikes serve as a kind of compensation for putting up with everything safe and mundane in this world, a thumb in the eye of caution.

All motorcycles do this to some extent, but Ducatis are the image on the recruiting poster.

I took my black 900SS for a long ride this weekend (maybe the season’s last, as it’s supposed to snow tonight) and sat in my workshop, warming up and looking at the bike for a while when I got back.

I happened to glance over at my glass trophy case, where I keep memorabilia-odd souvenirs, old tank badges, models, etc.-and noticed that I still had a spare set of silver velocity stacks left over from my first 900SS, as well as a Vi2-scale Tamiya model of the black Ducati, carefully assembled years ago by my late father-in-law, Fred Rumsey.

Behind the velocity stacks, on the middle shelf of the trophy case, was an ancient pack of crumbling Camels. They’d come out of the zippered tail compartment of my 900SS seven years ago, when I sold the bike to my friend in Colorado.

I always carried them there-for scenic roadside stops and reflective episodes of bike appreciation-along with two sparkplugs, a tool roll and a Zippo lighter. The Zippo, which I’d purchased at a military PX in a place called Phan Rang in 1969, was in the trophy case as well. Right near the cigarettes.

A small red light came on in my brain, but I ignored it-for the time being-and opened a Diet Coke. The kind with caffeine. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue