SUZUKI GS1100E

The King B-4 the B-King

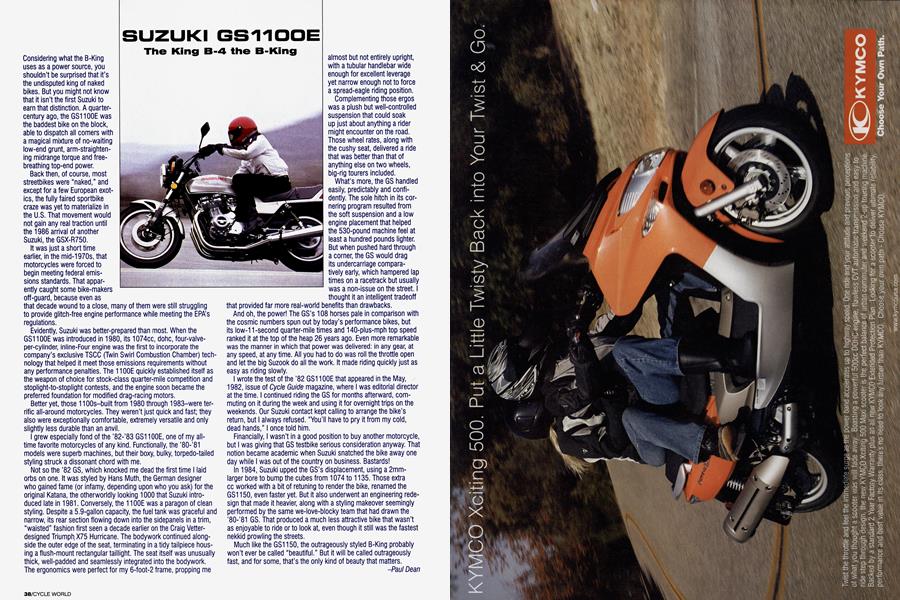

Considering what the B-King uses as a power source, you shouldn’t be surprised that it’s the undisputed king of naked bikes. But you might not know that it isn’t the first Suzuki to earn that distinction. A quartercentury ago, the GS1100E was the baddest bike on the block, able to dispatch all comers with a magical mixture of no-waiting low-end grunt, arm-straightening midrange torque and freebreathing top-end power.

Considering what the B-King uses as a power source, you shouldn’t be surprised that it’s the undisputed king of naked bikes. But you might not know that it isn’t the first Suzuki to earn that distinction. A quartercentury ago, the GS1100E was the baddest bike on the block, able to dispatch all comers with a magical mixture of no-waiting low-end grunt, arm-straightening midrange torque and freebreathing top-end power.

Back then, of course, most streetbikes were “naked,” and except for a few European exotics, the fully faired sportbike craze was yet to materialize in the U.S. That movement would not gain any real traction until the 1986 arrival of another Suzuki, the GSX-R750.

It was just a short time earlier, in the mid-1970s, that motorcycles were forced to begin meeting federal emissions standards. That apparently caught some bike-makers off-guard, because even as

that decade wound to a close, many of them were still struggling to provide glitch-free engine performance while meeting the EPA’s regulations.

Evidently, Suzuki was better-prepared than most. When the GS1100E was introduced in 1980, its 1074cc, dohc, four-valveper-cylinder, iniine-Four engine was the first to incorporate the company’s exclusive TSCC (Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber) technology that helped it meet those emissions requirements without any performance penalties. The 1100E quickly established itself as the weapon of choice for stock-class quarter-mile competition and stoplight-to-stoplight contests, and the engine soon became the preferred foundation for modified drag-racing motors.

I grew especially fond of the ’82-’83 GS1100E, one of my alltime favorite motorcycles of any kind. Functionally, the ’80-’81 models were superb machines, but their boxy, bulky, torpedo-tailed styling struck a dissonant chord with me.

Not so the ’82 GS, which knocked me dead the first time I laid orbs on one. It was styled by Hans Muth, the German designer who gained fame (or infamy, depending upon who you ask) for the original Katana, the otherworldly looking 1000 that Suzuki introduced late in 1981. Conversely, the 1100E was a paragon of clean styling. Despite a 5.9-gallon capacity, the fuel tank was graceful and narrow, its rear section flowing down into the sidepanels in a trim, “waisted” fashion first seen a decade earlier on the Craig Vetterdesigned Triumph X75 Hurricane. The bodywork continued alongside the outer edge of the seat, terminating in a tidy tailpiece housing a flush-mount rectangular taillight. The seat itself was unusually thick, well-padded and seamlessly integrated into the bodywork.

The ergonomics were perfect for my 6-foot-2 frame, propping me almost but not entirely upright, with a tubular handlebar wide enough for excellent leverage yet narrow enough not to force a spread-eagle riding position.

Complementing those ergos was a plush but well-controlled suspension that could soak up just about anything a rider might encounter on the road. Those wheel rates, along with the cushy seat, delivered a ride that was better than that of anything else on two wheels, big-rig tourers included.

What’s more, the GS handled easily, predictably and confidently. The sole hitch in its cornering program resulted from the soft suspension and a low engine placement that helped the 530-pound machine feel at least a hundred pounds lighter. But when pushed hard through a corner, the GS would drag its undercarriage comparatively early, which hampered lap times on a racetrack but usually was a non-issue on the street. I thought it an intelligent tradeoff

that provided far more real-world benefits than drawbacks.

And oh, the power! The GS’s 108 horses pale in comparison with the cosmic numbers spun out by today’s performance bikes, but its low-11-second quarter-mile times and 140-plus-mph top speed ranked it at the top of the heap 26 years ago. Even more remarkable was the manner in which that power was delivered: in any gear, at any speed, at any time. All you had to do was roll the throttle open and let the big Suzook do all the work. It made riding quickly just as easy as riding slowly.

I wrote the test of the ’82 GS1100E that appeared in the May, 1982, issue of Cycle Guide magazine, where I was editorial director at the time. I continued riding the GS for months afterward, commuting on it during the week and using it for overnight trips on the weekends. Our Suzuki contact kept calling to arrange the bike’s return, but I always refused. “You’ll have to pry it from my cold, dead hands,” I once told him.

Financially, I wasn’t in a good position to buy another motorcycle, but I was giving that GS testbike serious consideration anyway. That notion became academic when Suzuki snatched the bike away one day while I was out of the country on business. Bastards!

In 1984, Suzuki upped the GS’s displacement, using a 2mmlarger bore to bump the cubes from 1074 to 1135. Those extra cc worked with a bit of retuning to render the bike, renamed the GS1150, even faster yet. But it also underwent an engineering redesign that made it heavier, along with a styling makeover seemingly performed by the same we-love-blocky team that had drawn the ’80-’81 GS. That produced a much less attractive bike that wasn’t as enjoyable to ride or to look at, even though it still was the fastest nekkid prowling the streets.

Much like the GS1150, the outrageously styled B-King probably won’t ever be called “beautiful.” But it will be called outrageously fast, and for some, that’s the only kind of beauty that matters. Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontElectric Chair

February 2008 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Road To Harleysville

February 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCControlled Motions

February 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2008 -

Roundup

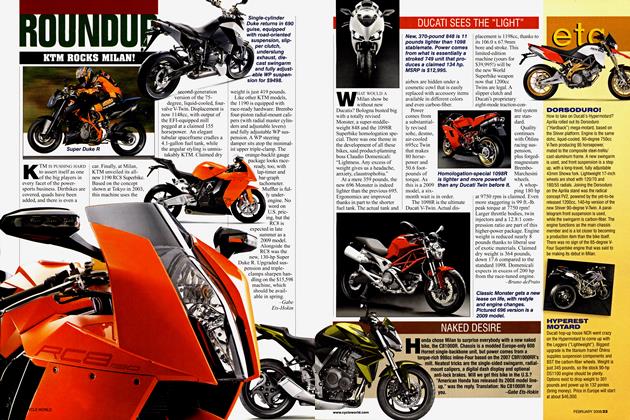

RoundupKtm Rocks Milan!

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin -

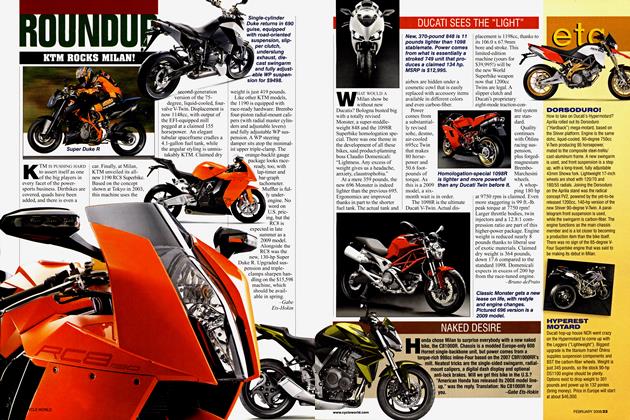

Roundup

RoundupNaked Desire

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin