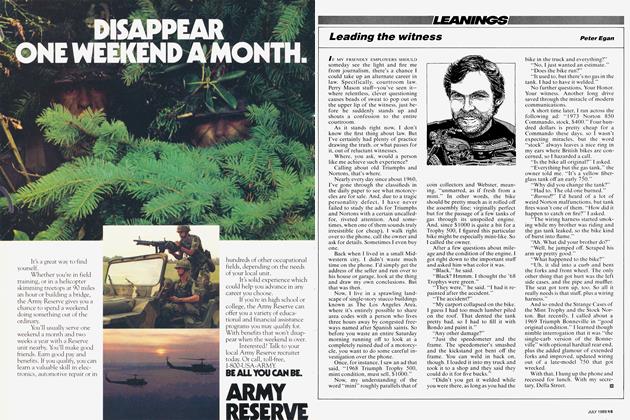

Spirit of the Wakan

American engine meets French frame. In rural Wisconsin, yet.

PETER EGAN

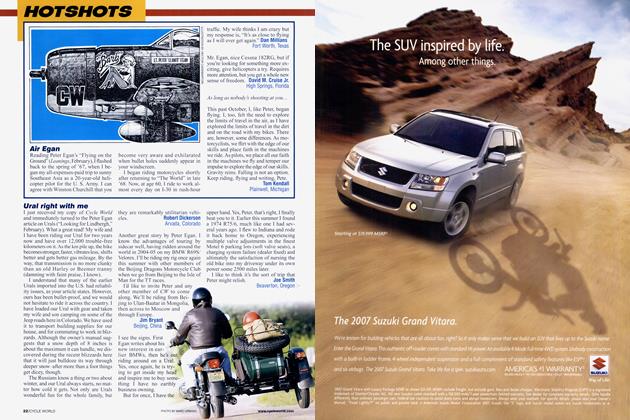

THERE'S JUST SOMETHING ABOUT A HARLEY SPORTSTER motor that triggers the imaginations of chassis designers. You've got that elemental mechanical architecture, as beautiful in its own way as a Vincent or Ducati V-Twin, crying out to be made the centerpiece of a light and lithe sportbike. Maybe something a little nimbler and more refined than the standard Harley item. Or something with the foot-pegs moved back, so you don't feel like a child seated on a toboggan when you hit the twisting backroads. A little more power would be nice, too.

It's a common dream, but it results in some uncom

mon bikes-Buell comes to mind, and so does Willie G. Davidson’s original XLCR Café Racer, not to mention the teaser XR1200 street-tracker, which we are told may or may not be sold here. And now we have an offering called the Wakan, a motorcycle that combines a French chassis with a Wisconsin-built, 100-inch S&S Sportster motor in a compact, 400-pound package.

Wakan (pronounced walk-un) is an Indian word meaning “sacred” or “intangible spirit” in Lakota, and the bike is the brainchild of a former nuclear engineer and trials-bike manufacturer named Joel Domergue, from Montpellier in the south of France.

I rode through this area on a bicycle trip from Paris to Barcelona in 1971, and I am here to tell you the local mountain roads are nice, and so is the weather. Also, motorcycles are more fun than bicycles going uphill. So are trains, cars and oxcarts, but never mind that for now.

Domergue was founder and president of Scorpa, a company that builds Yamaha-powered trials bikes for the European market (see “Rock Star,” CW, February, 2006). He sold that company in 2003 and used the money to pursue his next dream, which was designing and manufacturing the Wakan (www.engmore.com).

“Manufacturing” is probably a euphemistic term at this

point, because there are only three of these bikes in existence, with another 15 to be built this year. This first batch of bikes will be used mainly for testing and to attract investors.

Domergue-who stresses that all the jigs, molds, forms, etc. for manufacturing are already done and paid for-is hoping to build the bike in the U.S. He’s a great admirer, he told me, of American design and the can-do spirit that prevails here.

Hence the S&S engine and the search for investors in a U.S. factory.

With all this in mind, he flew a crated bike from France to Chicago, then hauled it up into the rugged hills of west central Wisconsin to the S&S factory at Viola for some final fitment and tuning.

This, of course, is where I

came in.

I live about 120 miles south of the S&S factory and grew up 35 miles from Viola. I speak fluent Wisconsinese, plus a smattering of French left over from trying to order

drinks on my bicycle trip. Also, I like Sportsters. So Editor Edwards asked if I could look at the Wakan-and take it for a ride on the very roads I grew up with.

Pas de problème, as we say here in the Midwest, where

towns have names like Prairie du Chien, Fond du Lac and La Crosse. The French have already been here once, arriving by canoe about 330 years ago. Harley-engined Wakans come naturally to us.

So I tossed my riding gear in the car and drove up to Viola

on a sunny but cold morning in late autumn-our last good one, as it would turn out, with 4 to 7 inches of snow on the Weather Channel horizon.

Viola is a little town of 644, surrounded by a ridge of almost surreally beautiful hills and bluffs. The S&S factory, a stridently clean and modern facility, is nestled in a scenic valley a few miles away. It has an engineering staff of 80 and a total of 350 employees.

When I got there, CW photographer Chris Cantle was shooting photos of the Wakan at the edge of the woods near the factory while Domergue looked on. I was also introduced to Rory Simpson, a transplanted Brit who used to

transplanted Brit who used to be France’s largest Ducati dealer. Another former nuclear engineer, he’s now working with Domergue on the Wakan project. He speaks fluent French and served as our translator for the day. Domergue’s English was about as good as my

French, which meant we wouldn’t soon be hired by the U.N.

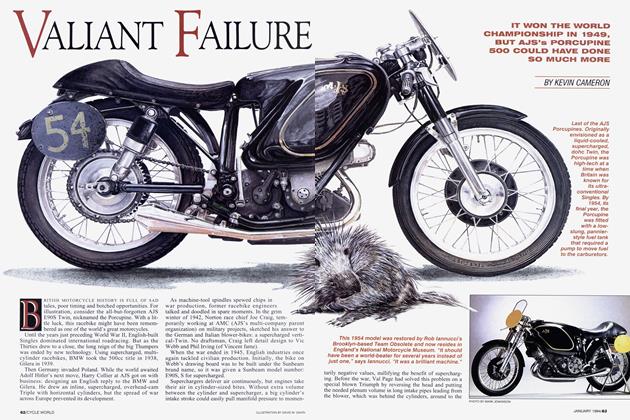

I stood back and looked at the Wakan, which is stunning in person. Small and waspish, it sits on a 54-inch wheelbase and 17-inch forged-aluminum Marchesini wheels designed by Domergue and built especially for Wakan. The robust

inverted fork is a 46mm Paioli unit, made under the upscale Ceriani label. There’s a single 340mm brake disc at the front with a six-piston caliper, and a 220mm disc at the back (soon to be 230).

Brake parts are made by AJP, a Spanish company that also supplies Yamaha.

The stout backbone frame, which curves parenthetically around the engine, is made in France from 76mm cold-drawn steel tube and doubles as the oil tank. The aluminum swingarm disappears into the back of the engine/transmission cases but pivots off the frame. The transmission itself is a fivespeed Harley box with gears

made in Italy. Primary drive is by belt, and a dry clutch is used. The battery is mounted under the engine, which sits quite low in the frame.

Elegant simplicity rules, with a single bolt holding the filter cover on the top of the “tank,” which is actually an airbox

with butterfly-regulated intake ducts. The seat also comes off with a single screw, revealing the real fuel tank, made of plastic and holding 3.4 gallons.

The engine is an S&S 100-cubic-inch “square” unit with a 4.0 x 4.0-inch bore and stroke. It normally puts out about

115 hp at 5500 rpm but has been cammed down slightly here for useful torque on the backroads. S&S engineers Scott Sjovall and Brian Hyde said they hadn’t yet dynoed this engine but predicted it would produce 95 horsepower at the rear wheel. Much, much more is available, they noted.

Induction is through a 41mm Keihin flat-slide carburetor, modified to run at an angle so it can tuck under the airbox, but fuel-injection will eventually be used in the production bikes. “Fuel-injection,” Simpson explains, “will allow us to clean up the right-side gearcase by removing the electronic ignition bulge. And we’ll also eliminate this excrescence,” he says, pointing to the front oil-filter mount,

“by moving the filter under the engine.”

While we talked, a vintage Beech Staggerwing biplane with a big radial engine roared overhead, circled the factory and landed at the S&S private airfield on a nearby hilltop. Time, perhaps, to start our own air-cooled chunk of pushrod

radial, though Domergue prefers automotive rather than aviation comparisons. His goal with the Wakan, he told me, was to build “a Shelby Cobra on two wheels.”

“A 289 or 427?” I asked.

“Quatre cents vingt-sept!” he replied, surprised at the

“Quatre cents vingt-sept!” question. A 427!

A tall order. We’d see.

I suited up for the chilly afternoon and climbed on the bike. Nice riding position. The bars are dropped but-unlike so many current sportbikes-the seat is not too high, so you’re in a comfortable, natural riding position without standing on your head. Also, the bike is so narrow, the pegs are able to be relatively low and still meet a GP lean-angle standard of 55 degrees. For such a small bike, it’s quite roomy.

Interestingly, the clip-on-style bars can be flipped on the fork tops to give a more upright riding position.

A moment of choke and

the engine starts with a nice throaty exhaust note from the Italian-built exhaust system: mellow, but not excessively loud. I’ve been warned that the dry clutch might be abrupt, but it feels quite normal to me-maybe from too many years on Ducatis. I click into gear and head up the road. For about 100 yards.

Then the engine stops.

I coast back through the factory gates, we push the bike into the garage and Domergue and Simpson go feverishly to work. In a short time they’ve found the culprit, a piece of stray lint in the fuel pump. The perils of prototyping. The

bike fires up and I hit the road again.

This time I get all the way through the gears and find the gearbox precise and positive, and at the first stop sign it snicks easily into neutral from either first or second. Rolling through the twisties and sweepers again, I find the Wakan

be of that

one almost disappears beneath you, like a good set of skis. The only part of the bike in your field of vision is the top of the small instrument pod.

There’s a digital speedometer that can be switched to rpm readout, but the Wakan almost doesn’t need a tach. The bike has gobs of easy, unintimidating torque at low rpm and picks up speed with mounting ferocity as you twist the throttle, with a really nice wallop of power coming on as the revs climb toward the electronically limited 5500-rpm redline. I purposely hit the rev-limiter once in the name of Science and the engine stuttered, but

normally there’s no need to get near redline-which the S&S engineers claim is ultra-conservative, in any case. It’s the truck motor from hell. You can leave it in one gear and make the curving road disappear behind you in big, smooth surges of rheostatic speed.

The chassis is absolutely settled, firm but not too stiffly sprung, with excellent damping at both ends. It gets through mid-corner stutter-bumps unruffled, delivers a civilized ride, yet doesn’t dive excessively under hard braking with the effective and easily modulated front disc. Turn-in is neutral and instinctive; the bike just flicks wherever you want it to

go, but without a hint of twitchiness.

Overall, the Wakan is a pleasure to operate, stable, wellsorted and easy to ride. Some vibration seeps through the handlebars and makes your palms itch at certain rpm but it’s well under the annoyance threshold. Considering that you’re essentially holding on to a big, solidly mounted Sportster motor by a few nicely crafted pieces of pipe, it’s remarkably civilized.

civilized.

I rode the Wakan on backroads for several hours and had no desire to return to the barn and get off it. The seat is thinly padded but tractor-wide and well-shaped so there’s none of the usual butt fatigue. The pegs didn’t cramp my long legs and the seat/bar relationship was good for hours of riding, even with my rangy (some would say simian) arms. The engine is marvelous to listen to as you ride. It sounds like an amplified heartbeat, running on

about nine cups of Starbucks’ best. This, folks, is a very nice motorcycle.

We did, however, run out of gas. After hours of chasing a camera car around, the bike sputtered to a stop in front of a beautiful ridge-top farm. The farmer who lent us some gas turned out to be an S&S production-line employee (healthy pay raise recommended here). We thanked him and then, with cold, deer and darkness threatening, headed back to the factory.

While warming up with coffee, I talked to Domergue and asked him the big question: “If this bike goes into produc-

tion, how much do you think it will cost?”

He said it would probably be between $32,000 and $35,000.

Another obvious question was, why should somebody buy this bike rather than a Buell?

Domergue told me he has owned and ridden Buells and admires their chassis design and innovative engineering but sees the Wakan as a slightly different kind of sportbike.

“Buell, I think, covers up the Sportster engine and wishes they had something else. The Wakan is a celebration of the Sportster engine. It’s the centerpiece of the motorcycle, the soul of the bike.”

And then he adds, “There should be no conflict between being proud of the object and its utility as transportation.”

On the way home that night I pondered Domergue’s Cobra analogy. Was the Wakan really a two-wheeled 427 Cobra?

Not exactly. The Wakan is more refined and subtle than the big Cobra, a little less of a beast. (“We can easily fix that,” Sjovall told me.) Yet it’s still all the beast you really need-just right for backroads and the real world. And it is, undeniably, a skillful melding of a classic American engine and an aesthetically stunning foreign chassis.

I hope the Wakan folks succeed in building their factory. Somewhere in the Wisconsin hills would be nice, right near Viola. □