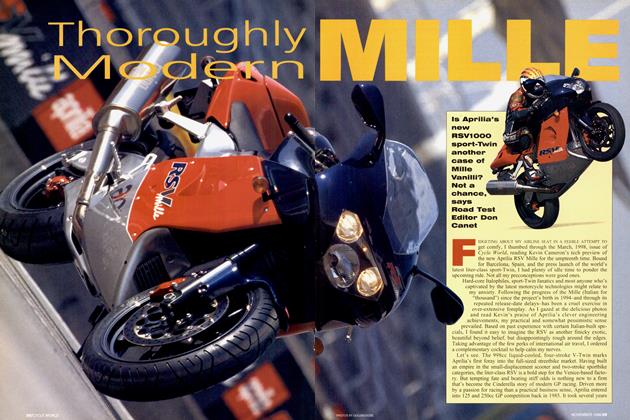

RIDE CRAFT

EAGLE RIDER: An auto-racing legend combines skill and judgment on two wheels

Be a better rider #3

NICK IENATSCH

FROM 1959 TO 1970, DAN Gurney survived and thrived in a sport where many died. In Formula One car racing, he competed in 88 races and scored 21 podium finishes, including seven wins. During that same era, he successfully raced and won in World Sports Cars, Indy Cars, Trans-Am, Can-Am, even NASCAR (five-time winner of the Riverside 500-miler), standing on top of the podium 49 times in 306 starts. Big horsepower and huge speed were Gurney's world. While the engines and aero dynamics of Gurney's heyday could rush him down tree lined straights at more than 200 mph, safety technology lagged miles behind. Full-face

helmets, five-point seatbelts, fireresistant fuel cells, impact-absorbent steering columns and even gravel traps simply didn’t exist. Mistakes were painful and often fatal. Grand Prix winners like Gurney had a rare combination of skill and judgment, and it’s this exact combination that street riders need to fully and safely enjoy our sport.

Gurney’s motorcycle passion started about 1947, before his first car race in 1955, but he soon realized,

“.. .that my height and weight might not be perfectly suited to motorcycle racing,” joked 6-foot-3 Gurney from his All American Racers office in Southern California. “But I was really into the bike-racing scene, and I knew who all the guys were. My buddy got a ’36 Harley and had to store it at my house to keep it secret from his parents, and that was my first ride. I was 16. Then I bought a used ’51 Triumph Thunderbird.” Gurney paused and laughed again.

“I painted that Triumph in my Mom’s kitchen. The whole room looked a bit rosy after that.”

The young man’s talent in a car was blossoming, but few know that Gurney twice raced a dirtbike in California’s famous Big Bear Run. “The first time, I think it was ’57,1 got sand in the carb of my Matchless and had to quit, but the next year I finished 21st out of about 700 on my Triumph TR6 (Gurney’s pal Bud Ekins won it that year). I got the TR6 when I returned from Korea, and in those days you could just ride into the mountains from our house in Riverside.”

By 1959 Gurney had been racing cars in the States for four years and was poised to enter F-l and racing’s history books. But how many of the European sporty-car elite knew that Gurney used a lowly motorcycle to stay in racing trim?

“Riding a dirtbike well takes an incredible feel for traction and speed, probably more so than a car,” Gurney relates. “My friend Skip Hudson and I used to go up near March Air Force Base and make a track. We’d race each other and we’d race the stopwatch. That was our only gauge back then, figuring out how to improve our times, how to go quicker.

“We also made dirt tracks around the orange groves, basically looking for limits. I know riding bikes helped me figure out cornering arcs and how to get traction. It sure kept me sharp.”

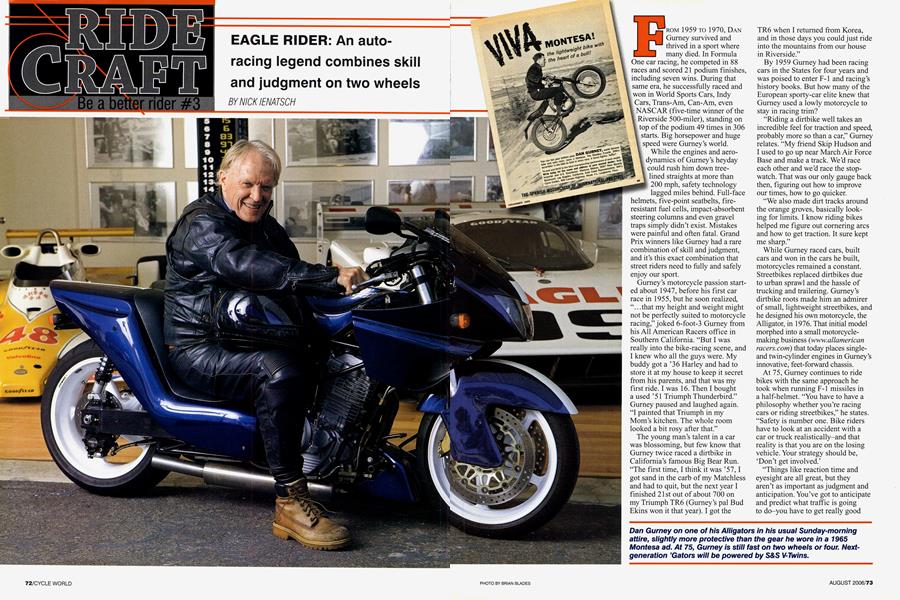

While Gurney raced cars, built cars and won in the cars he built, motorcycles remained a constant. Streetbikes replaced dirtbikes due to urban sprawl and the hassle of trucking and trailering. Gurney’s dirtbike roots made him an admirer of small, lightweight streetbikes, and he designed his own motorcycle, the Alligator, in 1976. That initial model morphed into a small motorcyclemaking business (www.allamerican racers.com) that today places singleand twin-cylinder engines in Gurney’s innovative, feet-forward chassis.

At 75, Gurney continues to ride bikes with the same approach he took when running F-l missiles in a half-helmet. “You have to have a philosophy whether you’re racing cars or riding streetbikes,” he states. “Safety is number one. Bike riders have to look at an accident with a car or truck realistically-and that reality is that you are on the losing vehicle. Your strategy should be, ‘Don’t get involved.’

“Things like reaction time and eyesight are all great, but they aren’t as important as judgment and anticipation. You’ve got to anticipate and predict what traffic is going to do-you have to get really good at predicting your short-term future. Don't paint yourself

into a corner where you’re out of options if the unexpected happens.”

In traffic, Gurney is focused on not getting caught up in others’ mistakes.

“I haven’t had to use my horn in traffic much because I work pretty hard to stay clear. I don’t like to scare people with a loud pipe blasting past because they will sometimes react dangerously. And if I ever feel road rage, I know I’ve put myself in the wrong position.” In the past, Gurney has had at least one unflattering experience with road rage.

“I was young and racing cars almost every weekend. My buddy Max and I were headed north on the freeway and I was moving through traffic carefully in my Cougar. There was a spot ahead about three car-lengths long and I slid into it. Right away, three guys in a Chevy started honking, so I gave them the ‘number-one’ sign. They swerved around us and got in front, then slammed on the brakes. Max said, ‘You know, (stockcar legend) Curtis Turner wouldn’t let them do that.’

“Well, that did it. The third time these guys slammed on the brakes,

I legged that Cougar and pushed my bumper right up into their trunk, then kept accelerating and swerved around them. As I came up beside them, the driver swerved really hard toward me. I swerved, too, and even though we hit, I kept going straight. The Chevy didn’t, and I looked in my mirror to see a huge pile-up on the freeway, cars spinning everywhere. Thankfully, there were no injuries, but I was called into the Highway Patrol office to explain what had taken place. That taught me to control any road rage because if some-

one had been injured or died in that incident, I would never have forgiven myself. Having all that false pride is a bad idea, and I’ve learned to just let things go, especially on a bike. You won’t win a fight on a bike.”

Nowadays, this old racer is tough on himself when he breaks or bends his own unwritten rules regarding speed and risk-taking. “There have been times I’ve gone a bit too fast or taken too big of a chance. We all have. But it gets back to what I said about leaving some room in case the unexpected happens, whether that’s a fluid spill in a blind comer or whatever. I like to leave a large margin for error, and if I use up that margin, I have a real good talk with myself.

“If we have a new rider along, I tell them, T don’t care how slow you go, you don’t have to be ashamed of anything. Just nibble away at this sport,

get smoother and better balanced, and the enjoyment increases without increasing the danger.’ ”

Gurney the motorcycle rider has hit the pavement once. “I came around a comer on my favorite backroad and saw two police cars ahead, parked on the shoulder with their lights going at the scene of another accident. I rolled off the throttle at about 55 or 60 mph and all of a sudden I was hit from behind by a guy in my riding group who wasn’t paying attention. He was going about 80 and suddenly I was going about 55 or 60 without my bike!

I broke my wrist and many bones in my feet. The guy who hit me had a history of making mistakes on the street, and I never should have been riding with him. This time he took me out. Don’t ride with guys like that.”

Proper judgment is number one in Gurney’s book, but skills are a very close second. “A rider needs to find a place where he can work on things without getting hurt. For me, it was dirtbikes and cars, learning to be smooth, work with traction. You need to practice things like emergency braking long before you have to make a real emergency stop. Try a stop from highway speeds and see how long it takes to get stopped. Go to track days to see what your bike can and can’t do, to find the limits. Track days, done right, are a great way to learn your bike.”

One of America’s greatest racetrack heroes stresses the need to keep it safe and sane on the street, noting that hard charging and big speed create unwanted police attention that will ultimately lead to a suspended license. Or worse.

“You shouldn’t ride at racing speeds on the street. It’s just not fun riding that close to the limit all the time.”

That’s Mr. Gurney talking.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

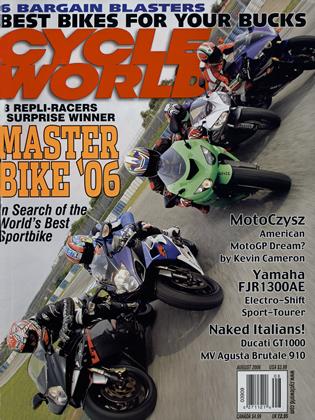

Up Front

Up FrontPassages

August 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBeasts of Burden

August 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Why's of Efi

August 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2006 -

Roundup

RoundupOf Crossbreeds And Concept Hybrids

August 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupCrf45o Revision Decision

August 2006 By Ryan Dudek