Garaj Mahal

Mr. Wilzig builds his dream house

MARK JENKINSON

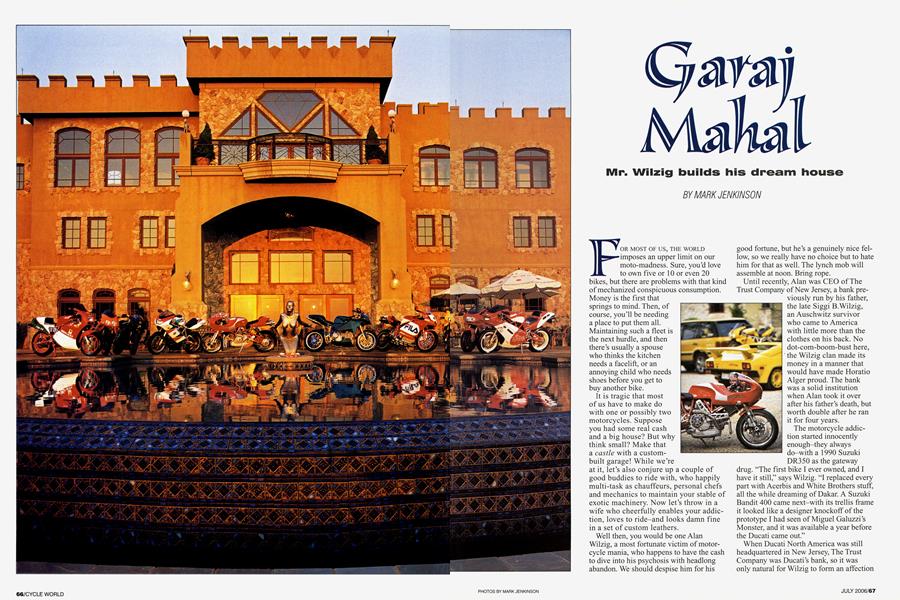

FOR MOST OF US, THE WORLD imposes an upper limit on our moto-madness. Sure, you’d love to own five or 10 or even 20 bikes, but there are problems with that kind of mechanized conspicuous consumption. Money is the first that springs to mind. Then, of course, you’ll be needing a place to put them all. Maintaining such a fleet is the next hurdle, and then there’s usually a spouse who thinks the kitchen needs a facelift, or an annoying child who needs shoes before you get to buy another bike.

It is tragic that most of us have to make do with one or possibly two motorcycles. Suppose you had some real cash and a big house? But why think small? Make that a castle with a custombuilt garage! While we’re at it, let’s also conjure up a couple of good buddies to ride with, who happily multi-task as chauffeurs, personal chefs and mechanics to maintain your stable of exotic machinery. Now let’s throw in a wife who cheerfully enables your addiction, loves to ride-and looks damn fine in a set of custom leathers.

Well then, you would be one Alan Wilzig, a most fortunate victim of motorcycle mania, who happens to have the cash to dive into his psychosis with headlong abandon. We should despise him for his for all things red, raucous, loud and Italian. “I got my first Ducati at a charity auction I hosted,” he recalls. “They were my clients, and I got Ducati to donate an M750 in the hopes that I would be the high bidder. I was. I spent more money customizing that bike than its retail value. NASA and the Air Force combined haven’t spent as much on carbon-fiber!”

good fortune, but he’s a genuinely nice fellow, so we really have no choice but to hate him for that as well. The lynch mob will assemble at noon. Bring rope. When Ducati North America was still headquartered in New Jersey, The Trust Company was Ducati’s bank, so it was only natural for Wilzig to form an affection

Until recently, Alan was CEO of The Trust Company of New Jersey, a bank previously run by his father, the late Siggi B.Wilzig, an Auschwitz survivor who came to America with little more than the clothes on his back. No dot-com-boom-bust here, the Wilzig clan made its money in a manner that would have made Eloratio Alger proud. The bank was a solid institution when Alan took it over after his father’s death, but worth double after he ran it for four years.

By now the monkey was firmly on Alan’s back, and bikes started finding their way out to eastern Long Island in quick succession-a 900SS acquired at another charity auction, then a 2001 MH900e Hailwood.

“I didn’t bid on the internet auction that Ducati had for the MH900s, but the devils kept one aside for me, figuring I wouldn’t be able to resist for long. It wasn’t practical, there was no seat for (then girlfriend, now wife) Karin, but it was beautiful so I bought it anyway. It lived in the conference room of the bank. Ducati liked that, and the bike still has zero miles on it.”

For gamblers and collectors, the internet is a dangerous, evil entity if you only sleep four hours a night.

A Laverda Formula 750 (“Orange is a happy color”), a 1985 750 Fl Due (“Classic Italian tricolore, had to have it”) and a 1999 Bimota DB4 with titanium exhaust that screams “NASCAR” in Italian were all purchased in latenight forays on eBay.

Surprisingly, Alan has actually been very fiscally responsible in acquiring his collection. After all, the rich don't get rich by working harder than the rest of us; they get that way by spending their money better than the rest of us.

Many of the bikes in the Wilzig stable have been bought secondhand at bargain-basement prices. Case in point, the recently acquired Ducati 999R in full FILA livery. The bike was purchased used from a Texas dealer who had already put an additional $15,000 in upgrades into the $35,000 bike and then sold it to Wilzig for $26K. The bike had 940 miles on it. All proof that Mr.

Wilzig went to Wharton and knows how to drive a bargain.

“When I bought the Philippe Starck Aprilia 6.5,1 knew I had turned a corner,” he says. “That bike officially made me a collector; it sits in the living room of my Manhattan townhouse and was purchased just to look at. Same with the 1953 Moto Guzzi Cardelino Lusso. I don’t love Guzzis, but for $2400 there was no painting I could buy that gives me as much pleasure to look at as that cute little 73cc puppy.”

The centerpiece of Wilzig’s collection is a bike he designed. Well, sort of...

“I love every bike that Massimo Tamburini designed, but I don’t like inline-Fours, so when the MV Agusta F4 came out I was as awestruck as anyone by the design but I wanted it to be a Twin. I collaborated with Alan Ortner and David Myles to combine the bodywork of an MV Agusta with the running gear of a 998 Ducati. David provided the silver-aluminum carbon-fiber and Alex did the machining, engineering and assembly. Martin Wong from Motowheels was also a huge help with the wheels and magnesium swingarm. The blue paint is 21 coats, all transparent, so you can see down to the reflective carbon-fiber. It looks like a Fabergé Easter egg. I don’t ride it, but I love it. For me, it’s the best of all things Tamburini.”

Having recently sold the bank, Wilzig now has more time to ride and a bit more cash in hand, so the collection is growing fast. KTMs are the new affliction, a Duke II and an Adventure S in full Galouises/Dakar livery garaged in New York for urban assault. A third home in Spain serves as base for European rounds of the MotoGP season and houses a Benelli Tornado and another KTM Adventure S.

Then there’s the private racetrack that’s being built...

“The Hamptons isn’t a particularly great area to ride in-too much traffic and it’s flat as Florida,” he explains.

“Besides, the garage at the castle is getting a little tight.

It’s time to move on. I just bought a house and 300 acres in upstate New York. I’ve been doing a lot of track days recently, including three days of one-on-one with Doug Polen, so I’m in the process of laying out a 1.5-mile road course on the property that I’ll pave next year.”

The funny thing is, I’ve heard this story before; from George Barber, in fact, who started out as mildly obsessed and let the passion grow unchecked into an evangelical message on the divine power and beauty of speed, now manifest as the Barber Motorsports Park &

Museum outside Birmingham,

Alabama. Give Wilzig another 20 years and he may well be scheming to bring MotoGP to upstate New York.

After spending the better part of two days photographing Alan’s motorcycles, I’m sitting with my first cup of coffee in the early-morning light staring across Long Island Sound past Wilzig’s pool, trying to avert my gaze from the sculpture of his wife Karin as a mermaid.

I’m enjoying a “Lord of the Manor” fantasy as Eric (Alan’s personal chef, major-domo and riding buddy) places breakfast in front of me. I’m thinking that life is good when I’m confronted with a dilemma few of us ever face: Which of Alan’s bikes shall I ride today? One of the Bimotas? I’ve always wondered about the Laverdas. Wilzig still serves on the board of the bank, and today is one of those rare days when he can't ride, so I can pick just about anything. The Bimotas are a tempting treat, and the brand-new KTM 950 SM is winking at me seductively, but he just got it two days ago. It would be like asking a friend to swap wives on his honeymoon.

"Eric, is the FILA Ducati gassed up?" "Of course. Shall I bring it round?" "Yes, please do. I think I might enjoy a bit of a romp."

Life is good, but it could be better. I could have been born Alan Wilzig.

When not bumming poolside meals and exotic Italian rides, Mark Jenkinson works as a writer/photographer covering fashion, business, sports and automobiles. He also teaches photography at New York University and attends track days on his very own Yamaha FZR400.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBest of the Rest

July 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Fine Art of Riding Your Own Bike

July 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRossi's Woe

July 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2006 -

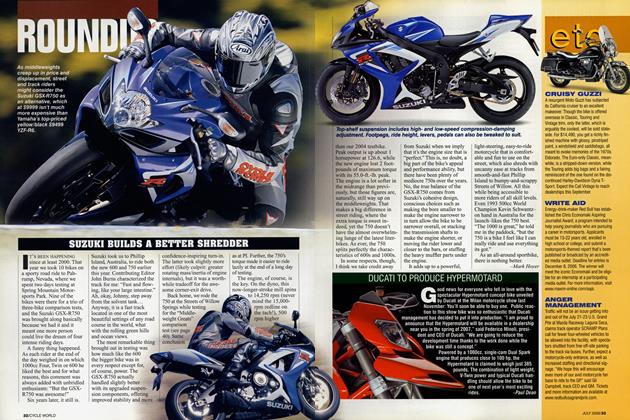

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Builds A Better Shredder

July 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupDucati To Produce Hypermotard

July 2006 By Paul Dean