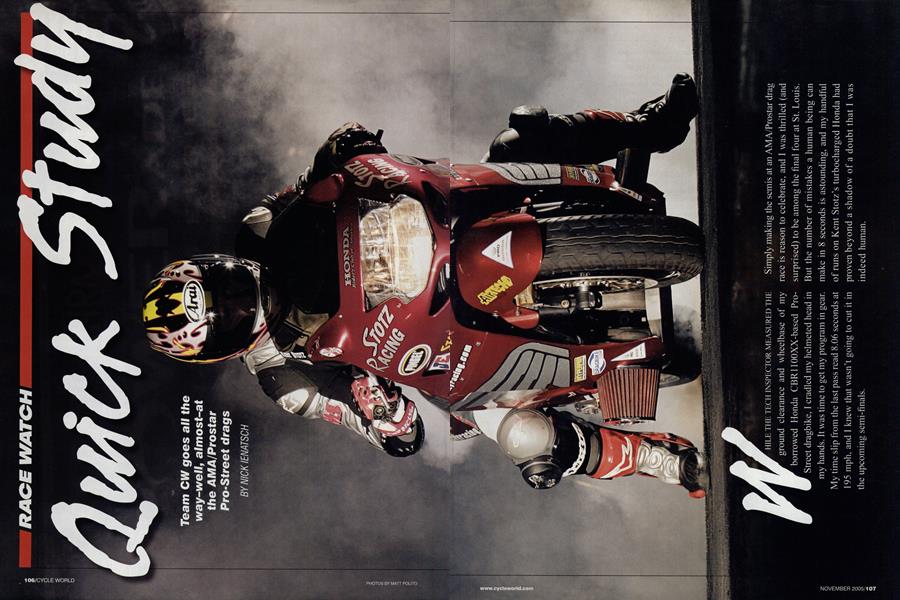

Quick Study

RACE WATCH

Team CW goes all the way-well, almost-at the AMA/Prostar Pro-Street drags

NICK IENATSCH

WHILE THE TECH INSPECTOR MEASURED THE ground clearance and wheelbase of my borrowed Honda CBR 1100XX-based Pro-Street dragbike, I cradled my helmeted head in my hands. It was time to get my program in gear. My time slip from the last pass read 8.06 seconds at 195 mph, and I knew that wasn't going to cut it in the upcoming semi-finals.

Simply making the semis at an AMA/Prostar drag race is reason to celebrate, and I was thrilled (and surprised) to be among the final four at St. Louis. But the number of mistakes a human being can make in 8 seconds is astounding. and my handful of runs on Kent Stotz's turbocharged honda had proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that I was indeed human.

There are two names to know in ProStreet: Kent Stotz and Barry Henson. Stotz was my tuner, rider coach and sponsor for the weekend at the PR Factory Store National at Gateway International Raceway. He is a four-time class champion and the first to crack 200 mph. Most Pro-Streeters have the same goal: ride as well as Stotz. Thank God I had him in my comer.

Henson would be my opponent in the semis. He not only wears the numberone plate, but provides chassis, fuel-management and turbo parts to more than 90 percent of the Pro-Street class from his Florida-based shop, Velocity Racing. My bike was the sole Honda in a sea of Suzuki Hayabusas, with Henson leading the charge despite a recent leg operation.

Stotz and I huddled over his computer, downloading data from my second-round win over Tim O’Neil. The Magneti-Marelli data-acquisition system that Aussie Imports’ Steve Nichols grafted onto the

CBR-XX is the first of its kind in this paddock, and it gave us a definite edge over the competition, replacing the six disparate systems used on last-year’s bike with a single component. Nichols is a genius with data, and Stotz isn’t far behind.

“Look at this,” Stotz said, pointing to the throttle and clutch graphs. “You staged at 8700 rpm and that’s perfect, but you were too slow with the clutch and too quick with the throttle, and that put you into the rev-limiter right here. As soon as the clutch locked up, the tire spun and that’s what killed your 60-foot time (a dreadful 1.496).”

“You did the right thing by closing the throttle and shifting to get things hooked up again,” he continued. “At this point, O’Neil had you beat, but you then put together a perfect run, with perfect shift points. You did a good job of recovering and sticking with it.”

O’Neil may have killed me through the first 330 feet, but things got crazy when his ’Busa spun its rear tire, slewed sideways and then wheelied, all in less time than it takes to read this description. The bottom line in Pro-Street is this: He who makes the last mistake loses. My am sucked, but it sucked early.

O’Neil’s dramatic run left him whitefaced and shaking, but that’s why fans love Pro-Street. These bikes make 500plus horsepower, run on relatively narrow 190/50-17 rear tires and don’t have the benefit of a wheelie bar, so rider input is just as important as chassis setup and power delivery.

Back to preparation. “You’ve got to be ready to go earlier,” Stotz told me after my second practice run. “You’re used to roadracing, where you get a 3-minute hom, have time to put on your helmet and take your warm-up lap. That’s a long time to get ready. Things happen a lot more quickly here.”

Is anyone ever “ready” for a 7.2-second,

200-plus-mph run? My first pass was a 7.9, but I was late on the shift (horn) but ton in every gear. On my fourth pass, I released the clutch perfectly but my upper body and head weren't ready and I was thrown rearward like a whiplash victim. (If you've ever been spiked in the face with a volleyball, you know the feeling.)

I then turned a 7.7 in qualifying, but wheelied hard in second gear. I won the first round of eliminations with an 8.0, but got off the groove and spun the tire in fourth, fifth and sixth gear, rattling the rev-limiter and painting a black line with the tire the entire length of the strip.

And get this: Stotz’s creation is so overwhelmingly fast that I never managed to get my boots on the footpegs all weekend, instead leaving them to dangle in the air through the lights at more than 190 mph. I know that sounds amateurish, but I simply didn’t have the brain capacity necessary to ride the bike and locate the pegs.

My reaction times-the time it takes for the front wheel to break the staging beam after the green light flashes-were a joke. Whereas the top runners regularly need only .020 to .070 of a second, I managed just .122 to .282. Why? Simple: fear. Releasing the clutch with authority not only takes precision timing, but a belief that the 675-pound monster won't park you on your backside as it wheelies out from under you. And that does happen. Launches are nothing short of brutal, yet overdoing the throttle or being too "harsh" with the clutch will leave you wishing for something as nice as "brutal." Stotz's CBR scared me in that "I know I'm gonna die, but I can’t stop giggling” way, and I loved every second of it.

Have you heard about Street Chaos? On Saturday nights during Prostar weekends, Street Chaos is a “run-whatchabrung” event with plenty of betting and B.S. I made four passes and my reaction times in the last two runs were .024 and .037. Not too shabby, eh? Too bad the only numbers that count are the ones made during actual qualifying and eliminations.

Pro-Street dragracers seek seven seconds of perfection. During my dozen runs on Stotz’s Honda, I had a few instances of goodness. My .024 reaction time at Street Chaos was good. My 60-foot time in the first qualifying run was 1.265, and that’s good. My top speed in the second round of eliminations was 195 mph, and that’s in the ballpark. I covered the eighthmile in 5.058 seconds on my second pass, and that’s okay. My best elapsed time in the quarter-mile was 7.571. Getting close. As Stotz snapped shut the laptop and ace mechanic Mark Harrell buttoned up the clutch cover, we all knew that beating Henson would require every good thing I’d done so far, all bundled into one run.

Henson and I would be the first to run. Despite the extreme heat and humidity, I sat on my bike fully suited and watched the lights cycle for the Pro-Stock bikes ahead of us. My mind clicked through the burnout process: Throw away the clutch to spin in the water. Idle out and clamp on the front brake. Throw out the clutch again and smoke the rear tire at moderate revs in first gear while leaning the bike right and left to heat the rubber evenly, all the while watching Stotz for rpm and lean angle. Watch for Harrell’s sign to ease off the front brake to allow the bike to spin to the line. Find neutral, flip the headlight switch to high beam to start the boost controller, pull in the clutch and wait 5 seconds for the boost controller to enable, signaled by a flashing green light on the dash. Engage first gear and pre-stage.

Stotz had dropped the pressure in the Mickey Thompson rear tire to 7.5 psi, half a pound lower than in previous runs. Because I had spun the tire so hard against O’Neil, Harrell had me hold my burnout longer than before. Harrell had gone to the starting line prior to each of my runs, looking for optimum traction and making chalk marks for front-wheel alignment. Drag racing is a team sport, but Stotz and Harrell could only do so much. I lined up on Harrell’s mark and clicked the transmission into gear.

A little clutch movement rolls the bike into the pre-stage beam and I bring the revs up enough to just flicker the shift light mounted right in front of my helmet. Without caring what Henson is doing, I move into the second staging beam first because I’ve been victimized by being late and thus unprepared for the lights.

This is all-or-nothing time. Win or go home. My mind focuses on my clutch hand, willing it to trust that Stotz has programmed the boost from relatively low levels in the first few gears to tremendous (and secret) levels in the top gears. I’ve got to snap that clutch out and ride this thing, because Henson surely will.

I came to St. Louis extremely nervous about the timing lights. Despite having made thousands of dragstrip mns during magazine testing, I had only gone when I was perfectly ready, never on the green. So I found myself in a Prostar semi-final and it was probably only the 20th time in my life that I had ever tried to “cut a light.”

Both of Henson’s staging lights are on and I feel the tug on the clutch, the itch in my fingers, my butt planted against the thin piece of fiberglass that serves as a seat. Our engines are screaming, the fans are pressed against the fences or standing on their seats. I’ve never been so nervous, so on edge, so alive. I know the bike is shaking with every slam-slam-slam of my heart against my ribcage. Oh Lord, this is great!

Stotz’s Honda gives me the chance to let it all hang out in one explosive, all-consuming rush for perfection. As much as I want to beat Henson, what I really want is a perfect run-a shot at a 7.2 and 200 mph. I would have bet anyone $10,000 that I could run those numbers. I knew I could do it.

The trick with a Pro tree is to leave when the amber lights flash, and I did, getting the jump on Henson’s Hayabusa with a clutch move that shocked my brain into momentary numbness. Then a single thought seeped through my tension-fried neurons: “Don’t let the engine hit the revlimiter. Nail the horn button!” My left thumb stabbed the button, activating the Pingel airshifter. But I shifted too early, and Henson’s Suzuki surged ahead half a bikelength. I hit second gear and I was still playing with the throttle, knowing that getting greedy would smoke the tire. Henson eased ahead another 4 feet. He led into third gear by 12 feet. I pulled back 2 feet in fourth gear, fifth brought me within 7 feet and my Honda was pulling like.. .well, unfortunately just like a turbocharged Suzuki Hayabusa with a number-one plate on it. Sixth gear saw me gain even more ground but it was too late, and Henson beat me by a bikelength.

I made a good pass, clocking my second-quickest run of the weekend-a 7.62 at 194 mph. But it was Henson’s 7.46-second, 190-mph effort that put him into the finals and me on the trailer. Stotz and I reviewed the data, spending a few hours observing a few seconds. Drag racing at this level is all about hours of intense pressure preceding moments of sheer insanityfollowed by hours of wishing for just one more pass.

As luck would have it, Henson fired his best bullet at me. In the finals, he spun his tire and slithered to a 7.7-second pass, losing to Trevor Altman’s stellar 7.4 effort. If only... □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreat Escapes

November 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTowns of the Blue Highways

November 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Tale of Two Powerbands

November 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2005 -

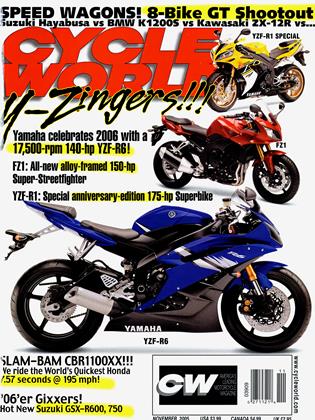

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Smokin' 6!

November 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMoto-Collectible: the Exotic R1

November 2005 By Calvin Kim