TRIPLE KNOCKER

JOHN OWENS

One cylinder, three cams, 15 minutes of fame

KEVIN CAMERON

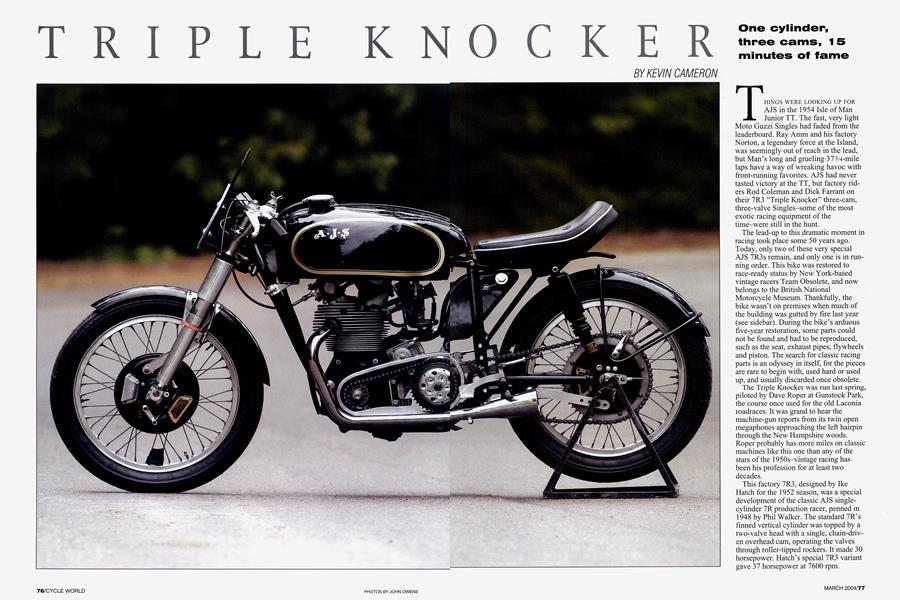

HINGS WERE LOOKING UP FOR AJS in the 1954 Isle of Man Junior TT. The fast, very light Moto Guzzi Singles had faded from the leaderboard. Ray Amm and his factory Norton, a legendary force at the Island, was seemingly out of reach in the lead, but Man’s long and grueling 373/4-mile laps have a way of wreaking havoc with front-running favorites. AJS had never tasted victory at the TT, but factory riders Rod Coleman and Dick Farrant on their 7R3 “Triple Knocker” three-cam, three-valve Singles-some of the most exotic racing equipment of the time-were still in the hunt.

The lead-up to this dramatic moment in racing took place some 50 years ago. Today, only two of these very special AJS 7R3s remain, and only one is in running order. This bike was restored to race-ready status by New York-based vintage racers Team Obsolete, and now belongs to the British National Motorcycle Museum. Thankfully, the bike wasn’t on premises when much of the building was gutted by fire last year (see sidebar). During the bike’s arduous five-year restoration, some parts could not be found and had to be reproduced, such as the seat, exhaust pipes, flywheels and piston. The search for classic racing parts is an odyssey in itself, for the pieces are rare to begin with, used hard or used up, and usually discarded once obsolete.

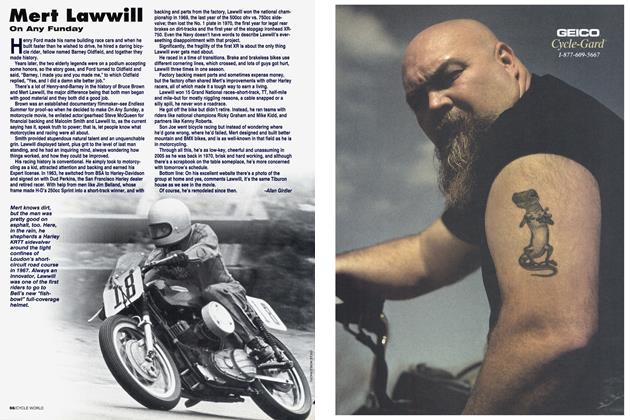

r~s~i last spring, piloted by Dave Roper at Gunstock Park, the course once used for the old Laconia roadraces. It was grand to hear the machine-gun reports from its twin open megaphones approaching the left hairpin through the New Hampshire woods. Roper probably has more miles on classic machines like this one than any of the stars of the 195 Os-vintage racing has been his profession for at least two decades.

This factory 7R3, designed by Ike Hatch for the 1952 season, was a special development of the classic AJS singlecylinder 7R production racer, penned in 1948 by Phil Walker. The standard 7R’s finned vertical cylinder was topped by a two-valve head with a single, chain-driven overhead cam, operating the valves through roller-tipped rockers. It made 30 horsepower. Hatch’s special 7R3 variant gave 37 horsepower at 7600 rpm.

The 1954 racing season was the British factory teams’ swansong-sales could no longer support prototype racing efforts. They continued to build production racers until that, too, ceased in 1962-63. Two World Wars had bankrupted Britannia. In the early 1950s, materials, food and fuel rationing had only recently ended, and times were still hard. AMC, of which AJS and Norton were part, had no export plan and its income faltered as small cars hit the market, giving consumers a cheap alternative to motorcycles as basic transportation. Despite the red ink, AJS designed, built and raced England’s only competitive twincylinder racer, the 500cc E90/95 “Porcupine,” winning the first postwar 500cc Grand Prix title in 1949. Add to this the aforementioned 7R production racer and more exotic 7R3 variant. Why this outpouring of expensive racing

R&D? Like the British Empire itself, AJS was pretending to have a future. In better times, a TT win brought instant sales success, so racing was business as usual. Yet the future obviously belonged not to face-lifted prewar Singles, but to higher-revving Twins and Fours. The Italians-Gilera, MV Agusta, Moto Guzzi and Mondial-would now take over. After them would come the Japanese. In 1954 England, design and will-to-succeed remained strong, for ideas cost nothing. All that was lacking was the money to make them real.

The 7R3's unique three-valve head was designed around the problem of making exhaust valves survive in an aircooled engine. Today, liquid-cooled motorcycle engines with four small cylinders have no such problem. Each time their tiny paired exhaust valves close, they make close con tact with a stable, cool valve seat into which they pour the heat just picked up during the previous sonic rush of 1700degree exhaust gas. Liquid cooling is recent-prior to 1984, radiator-equipped motorcycles were rare. Before that, aircooling depended on presenting adequate cooling-fin area to the rushing, gaseous coolant that surrounds us all: air. Single-cylinder racing engines in the 7R3 `s time generally had two large valves, and were built with the exhaust side of the head facing forward. On long pulls like those on the Isle of Man, cylinder-head temperature rose steeply, gener ating thermal expansion forces that tended to stretch the cooler intake side of the head. The frequent result was head and valve-seat distortion. When glowing-hot exhaust valves could no longer seat squarely, they lost much of the cooling effect of seat contact. Valve temperature went out of sight, leading to stretching, coning or outright breakage.

As in WWII aircraft-engine practice, racing motorcycle exhaust valves were given large, hollow stems, half-filled with sodium metal. Melting at 200 degrees, the liquefied metal oscillated back and forth during operation, carrying heat from the hot valve head to the cooler stem, then into the valve guide to establish a second cooling path for the valve. This brought its own problem: The very hot valve stem could now gum its lubricating oil. Over time, the gum hardened, sticking the valve in its guide. A series of collisions with the piston would then break off its head. Sometimes, the result was a gleaming stainless valve head halfburied in the piston’s solid aluminum crown-what Velocette’s former racing engineer Harold Willis called “penny-in-theslot.” Norton’s response to this was to pump engine oil through a spiral passage surrounding the Manx racer’s exhaust-valve guide-and then through a small oil-cooler. On some hot-running modem turbo engines, exhaust guides are cooled in this same way. Exhaust survival deserves careful design attention. valve

The 7R3’s Triple Knocker engine was cleverly designed to avoid all this, to keep running strongly while other designs lost valve seal or failed outright. AJS designer Hatch was near the end of a long career. He gave the AJS 7R3 two small exhaust valves in place of a single larger one-precisely what is done today. Prewar, he had designed Excelsior’s 1933 radial four-valve 250cc racer, and he knew that the smaller the valve, the more cool seat contact it has in relation to its hot head’s surface area. He also apparently knew something about heat-resistant alloys, for instead of choosing the usual 1925-vintage KE965 stainless used by Norton and many others, he had the 7R3’s two small exhaust valves made of a material with much higher heat strength, a new gas-turbine blade material called Nimonic 80A.

Now it becomes even more interesting. From his work with the four-valve Excelsior, Hatch knew the value of a centrally located sparkplug, which shortens flame travel to the practical minimum. Fast combustion is efficient. But choosing just two valves pushes the sparkplug off to one side, slowing combustion unless two plugs are used. With three valves, a central plug was easy.

Hatch next conceived a way to get cooling air to the hottest parts of his engine. The normal arrangement places one intake cam across the rear of the head, and one exhaust cam across the front. While mechanically neat (which is why this arrangement is used on almost all modem liquid-cooled engines), this creates a windless valley behind the exhaust cam that cooling air cannot reach. For successful cooling, air must msh at high speed through the fin space. Therefore Hatch used three cams-one inlet in the usual place, but with two exhaust cams, one for each exhaust valve, at right angles to it pointing forward. Smack in the middle of the space among the three was the sparkplug. Air coming over the top of the front wheel shot right between the two exhaust cams, doing a fine job of cooling the fins surrounding the central plug. Hairpin springs were used on the intake valve, helicals on the exhausts.

Why only one intake valve, rather than the two of his own Excelsior design or has been commonly adopted on modem four-valve engines? In 1952, the reigning gum of engine airflow was Harry Weslake, who had shown that more air could be gulped through one intake valve than through two. This was tme: Airflow into a hemi combustion chamber from a single valve can attach to the smooth, bowl-like inner chamber surface to achieve a high flow coefficient, better than that of paired intakes in a flat-sided pentroof chamber. Modem engines get their flow more from raw valve area than from anything else, but in the smalldiameter 75.5mm 7R3 cylinder there was no room for this. Design moves forward a step at a time. Hatch used the best technology of his era-a high-flowing single intake valve and two small, well-cooled exhausts. The shallow combustion chamber burned fast, needing only 31.5 degrees of ignition timing.

On the 7R production racer, a gold-colored magnesium camchain cover runs straight up the right side of the cylinder to the centrally located single cam. On the factory 7R3, the chaincase angles to the rear, driving the lone cam located near the intake valve. Bevel gears take the drive from intake to exhaust cams, and all valves-disposed radially as in Hatch’s previous Excelsior design-are operated by roller rockers.

The restored Team Obsolete machine I saw at Gunstock has many fine details to catch the eye. Tubular swingarm beams are tapered and, just as on modern GP bikes, the rear fender moves with the wheel The top fork crown is polished and gracefully cast with a receptacle for the Smiths tachome ter, driven from the left exhaust cam. Steering-damper adjustment is by a large wing-nut atop the steering stem.

Fork tubes are designed for lightness-small in diameter between the fork crowns, large where gripped by the lower crown’s pinch bolts, and small again below where they enter the sliders. Elegantly rising “swan’s neck” clip-ons have integral lever brackets. This bike has sticky Avon tires and modem Works Performance shocks, but in its heyday wore AMC “jampots,” a chubby early type of hydraulic shock with all the defects of its time-unsophisticated damping with a tendency to lose oil through the shaft seal. Sounds of traditional character emerge from the plain, open-ended megaphones, 7 inches long and 3 inches in diameter, making bystanders run for their earplugs.

Before the 1954 season, AJS engaged veteran TT racer and Vincent development engineer Jack Williams to improve the chassis of both the Porcupine 500 and the Triple Knocker.

Arriving in late 1953, he lowered the headstock height and frame backbone, dropping the center of mass with a pannier-style tank that rose only 3/4-inch above the backbone.

To lift fuel to carbs now above minimum fuel level, he introduced AC pumps. He shortened both rear suspension units and wheel travel to further lower the bike’s center of gravity. He replaced the swan’s neck clip-ons with a straight dropped design, trimming frontal area by lowering the rider.

Team politics were just as intense in the 1950s as today. Rider Rod Coleman didn’t like Hatch, who, he later related in a conversation with Team Obsolete’s Rob Iannucci, was not only secretive but also forbid anyone to enter his workshop. In the 1953 TT, Hatch shortened the gear ratio Coleman had chosen-without telling him-and the engine failed down Bray Hill. Coleman also complained of lack of spare parts, and that parts were not truly interchangeable. Does this sound like Biaggi’s complaints about Yamaha’s factory Ml MotoGP bike in 2002? The reason was the same: All available effort was going into new, higher performance parts, not into standardization. AJS not only had little budget, Coleman recalls it had no operations savvy, either. The mechanic who traveled with the bikes refused to do any work unless paid by the rider!

A 79 x 71mm 7R3-B was planned with towershaft cam drive instead of chain. Its sliding vertical spine would facilitate the rapid changes of compression ratio (using gaskets of different thicknesses) made necessary by national variations in fuel octane. Moving the head up and down in this way would be impossible on modem engines, whose squish bands require a fixed TDC clearance between piston and head. When the 7R3 was designed, the use of a turbulence-generating closetolerance ring around the combustion chamber to better mix the air/fuel charge in the cylinder was a new concept, not yet universally adopted. In the production racer 7R, tight squish would later allow compression to rise safely from 10.8 to 12.2:1.

A number of 7R3 cylinder heads were made to support continuing development. The one on this machine is stamped #9. Its intake port has been bored and sleeved to raise it to a steeper downdraft angle. In those days, a 15degree downdraft was normal. Today, it is more like 30 to 45 degrees. Flywheels and mainshafts were forged in one piece and an even shorter-stroke 81 x 68mm set had been made for testing. All cranks had tungsten balance weights. Curiously, the 7R3 used a very short connecting rod-only 5.875 inches between centers-while the production 7R rod measured 6.375 inches. For the 7R3 this gives a stroke-torod-length ratio of 1.91:1-a bit short of the 2.2:1 ratio found in many modem Superbike engines. The 7R3-B was to have used the same rod, but its shorter stroke yielded a 2.1:1 ratio. I suspect these were not so much considered choices as they were matters of convenience. All internal engine surfaces were polished-look into a modern NASCAR engine to see the same.

A peculiarity of this design is that the 15/i 6-inch carburetor is slightly smaller than the l3/8-inch intake port. In today’s designs, the extreme reverse is true-ports now are much smaller than either carbs or injection throttle bodies. The reason is that carburetors of the 1950s needed a lot of intake velocity to flow and atomize fuel, while modem systems do not. A designer or tuner therefore tested with various carburetors until he found one that gave the best compromise of acceleration, throttle response and top speed. Iannucci says that some 7R3 parts may have been consumed in later development of the production racers. Waste not, want not.

Today, everything has changed but the principles of design and its problems remain the same. The AJS 7R3 was not as successful as, say, Norton’s classic Manx or Velo’s KTT. But it did accomplish the main task of its design: keeping exhaust valves alive. Ray Amm’s Norton stopped in the 1954 Junior TT with a broken valve. Rod Coleman’s AJS kept running to a winning finish. □