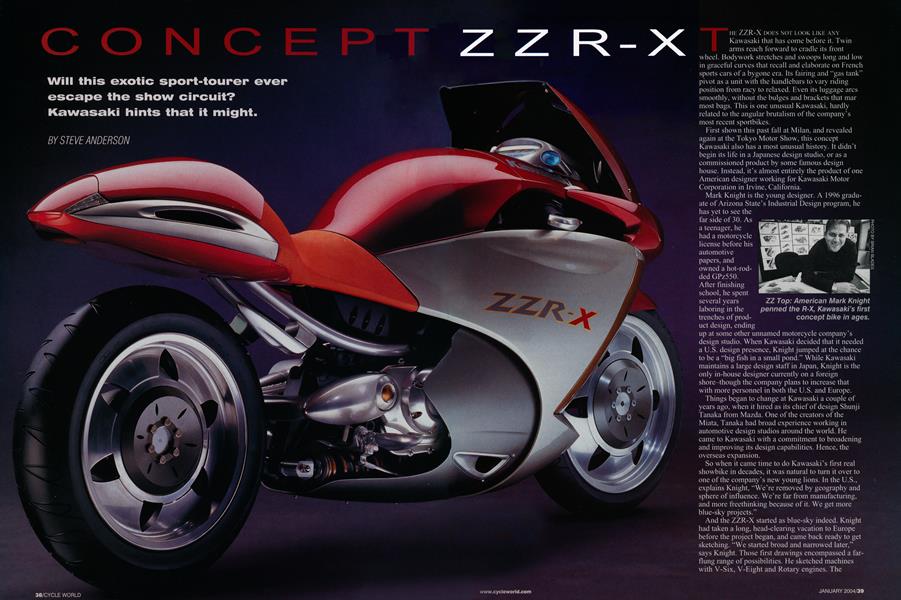

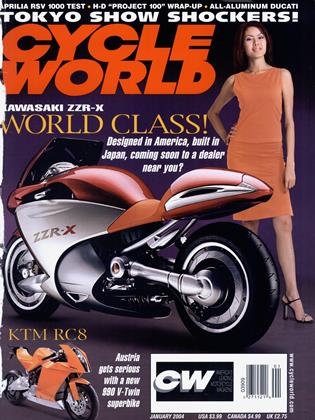

CONCEPT ZZR-X

Will this exotic sport-tourer ever escape the show circuit? Kawasaki hints that it might.

STEVE ANDERSON

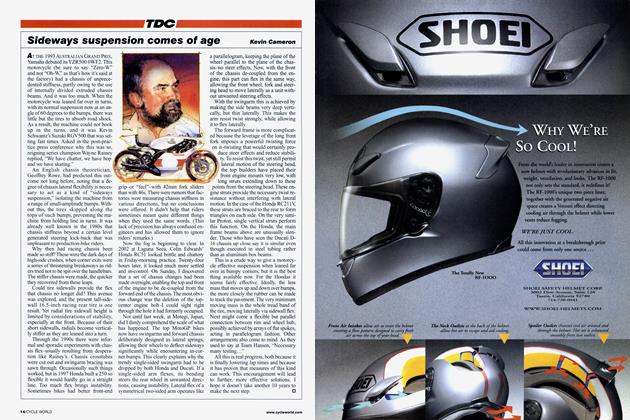

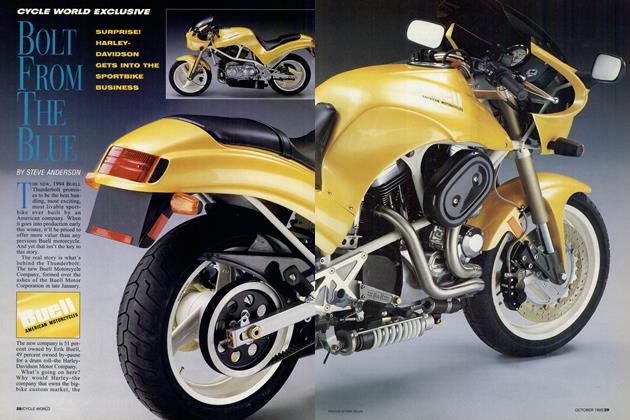

THE ZZR-X DOES NOT LOOK LIKE ANY Kawasaki that has come before it. Twin arms reach forward to cradle its front wheel. Bodywork stretches and swoops long and low in graceful curves that recall and elaborate on French sports cars of a bygone era. Its fairing and “gas tank” pivot as a unit with the handlebars to vary riding position from racy to relaxed. Even its luggage arcs smoothly, without the bulges and brackets that mar most bags. This is one unusual Kawasaki, hardly related to the angular brutalism of the company’s most recent sportbikes.

First shown this past fall at Milan, and revealed again at the Tokyo Motor Show, this concept Kawasaki also has a most unusual history. It didn't begin its life in a Japanese design studio, or as a commissioned product by some famous design house. Instead, it’s almost entirely the product of one American designer working for Kawasaki Motor Corporation in Irvine, California.

Mark Knight is the young designer. A 1996 graduate of Arizona State’s Industrial Design program, he has yet to see the far side of 30. As a teenager, he had a motorcycle license before his automotive papers, and owned a hot-rodded GPz550.

After finishing school, he spent several years laboring in the trenches of product design, ending up at some other unnamed motorcycle company’s design studio. When Kawasaki decided that it needed a U.S. design presence, Knight jumped at the chance to be a “big fish in a small pond.” While Kawasaki maintains a large design staff in Japan, Knight is the only in-house designer currently on a foreign shore-though the company plans to increase that with more personnel in both the U.S. and Europe.

Things began to change at Kawasaki a couple of years ago, when it hired as its chief of design Shunji Tanaka from Mazda. One of the creators of the Miata, Tanaka had broad experience working in automotive design studios around the world. He came to Kawasaki with a commitment to broadening and improving its design capabilities. Hence, the overseas expansion.

So when it came time to do Kawasaki’s first real showbike in decades, it was natural to turn it over to one of the company’s new young lions. In the U.S., explains Knight, “We’re removed by geography and sphere of influence. We’re far from manufacturing, and more freethinking because of it. We get more blue-sky projects.”

And the ZZR-X started as blue-sky indeed. Knight had taken a long, head-clearing vacation to Europe before the project began, and came back ready to get sketching. “We started broad and narrowed later,” says Knight. Those first drawings encompassed a farflung range of possibilities. He sketched machines with V-Six, V-Eight and Rotary engines. The themes ran from a sophisticated power-cruiser to a recumbent sporttourer-a design that contributed more than a few lines to the final ZZR-X. It was only after exploring a great garden of ideas that Knight got together with Kawasaki marketing and began to weed.

The theme of the bike emerged. The ZZR-X would be an up-market sporttourer, a machine that would offer escape, comfort and style. “It would slip through the air,” says Knight. “Its design would not age quickly.” It was consciously designed “against trend,” away from the current deconstructionist, exploding-sportbike style, those jagged and angular shapes that look both cutting-edge contemporary and oh-so aggressive.

“On those bikes,” says Knight, “when the wife comes up to it, she doesn’t say, ‘That’s pretty.’ Instead, she at least thinks, ‘Am I going to get hurt on that?”’ And for an expensive sport-tourer, it helps to have Significant Others on your side to help make the all-important buying decision.

Style set, the hardware became more real, too. The finished ZZR-X hides inside its bodywork, “a real engine that you’ve never seen,” teases Knight. He’s too much of the pro to say much more than that, though the indications are that it’s a fourcylinder, and he will hint that only a mere liter of displacement would be, “pushing it for this type of bike. You can assume it has more.”

There’s a subframe under the engine providing supports for the front and rear swingarm mounts, while a large muffler is hidden by the bodywork, tucked under the engine and as far forward as it will go, leaving the rear of the machine narrow and clean. The Elf-style twinarm front suspension is perhaps the least real thing about the design, though it certainly has been demonstrated to be workable. But on the ZZR-X as currently shown, the cable linkage designed to connect handlebars to front wheel has been left off, leaving the front end looking cleaner and perhaps concealing a design detail that Kawasaki doesn’t yet want to share with its competitors. Or perhaps, as with the first Kawasaki four-stroke GP design that was shown without an exhaust system, the company is simply ignoring unfinished details that would clutter up a showbike.

Other parts of the design are well thought out, though. Two anodized aluminum “ailerons” ride on either side of the fairing, and can be electrically opened as the ZZR-X travels down the road. The intent is to let the rider vary exactly how much air he wants, and on cold or rainy days, open the ailerons for more protection. Similarly, the variable riding position raises and lowers the entire “tank” and fairing, allowing the height of the bars to be altered by about 2 inches-enough to make a very substantial difference in riding position and comfort.

“We thought a lot about the wind sensation on this bike,” says Knight. He explains that in the bodywork’s lower position it was important to be able to feel the wind, while the higher position offers more protection. The mirrors are integrated into the fairing, sticking out just far enough to give a view beyond your elbows. With the real gas tank centrally located, room was available to make the conventional tank location into a storage space big enough to hold a full-face helmet.

Many of the mechanical details of the ZZR-X are novel, fascinating, and may very well be seen on production machines in the near future. Both clutch and brake levers pivot at their outside edge, and activate master-cylinders built into the handlebar tubes. The front and rear discs are inverted designs, with the calipers grabbing the discs from the inside, as on Buell XBs. Unlike the Buells, though, or any other motorcycle, the ZZR-X’s discs are conical rather than flat. Knight says that this helps put the disc out in the airstream, less shrouded by the wheel and tire, and thus helps cool the disc-which likely indicates that this is not an untested concept.

Final drive is by shaft, with perhaps the only surprising feature that it lacks a floating gearcase such as used on Moto Guzzis and BMWs, and the control of substantial anti-squat effects that can give. The extreme length of the swingann, though, will reduce the suspension-lifting effects of acceleration somewhat. Bump control is by twin shock absorbers under and parallel with the swingarm; they’re activated conventionally in compression by a linkage.

Perhaps the most innovative features of the ZZR-X are its instruments. They’re all a “glass panel” in airplane terminology, a color LCD bright enough to be seen in the daytime. The virtual display changes to emphasize the different monitoring possibilities, and a flashcard allows it to be reprogrammed. Knight talks about Kawasaki offering quarterly updates, downloadable from a website, as a simple reprogramming would allow a complete change of the instrument appearance. Basic GPS navigation is also built into the system, a feature that may someday soon be nearly standard on any motorcycle with touring pretensions. But the complex panel is flanked by simple digital clocks, which can function as stopwatches.

The saddlebags are also unique. Knight wanted to achieve several things with the luggage design, and he went through many iterations. A few early versions even had the luggage mounted up front, alongside the engine-a desirable location from a weight balance and stability point of view, but difficult to make practical unless you have an exceptionally narrow engine. The ZZR-X had to look sporty and clean when the luggage wasn’t in place, and some of the early designs made use of drop-down soft bottoms that could fold up when not being used. The final take, however, is more conventional, with removable hard bags that attach simply to the rear of the bike. Knight worked hard to make the bags look like slick briefcases, something a rider wouldn’t hesitate to carry up to his office if he commuted. He even looked into covering them with leather and other more exotic materials, something that is still under study.

The curvaceous lines of the ZZR-X carry more than a little Thirties deco romanticism in them, though filtered through a modern sensibility. Knight frankly admits that designers are very aware of the gender of the products that they work on, and if many modern sportbikes are aggressively masculine, the ZZR-X is instead sophisticated and feminine, the way an America’s Cup sailboat or a highperformance glider might be. He wanted a timeless design, “one that you could own for 10 years or more.”

As for the production possibilities of the ZZR-X, Knight had a few tantalizing comments. The bike was originally intended to be a runner, he says, though the three-month flog to get it ready for the shows didn’t leave time to complete that task. Almost all of the technology in it is proven and producible, though he indicates that the front suspension is one of the few areas where some changes might be made, if only for cost considerations. But whether a motorcycle specifically derived from the ZZR-X ever makes production, we think it is a harbinger of Kawasakis to come. When Tanaka took over the design department, his stated mission was to, “match designs to the level of Kawasaki’s engineering prowess.” The ZZR-X is just a hint of what that statement will really mean. U