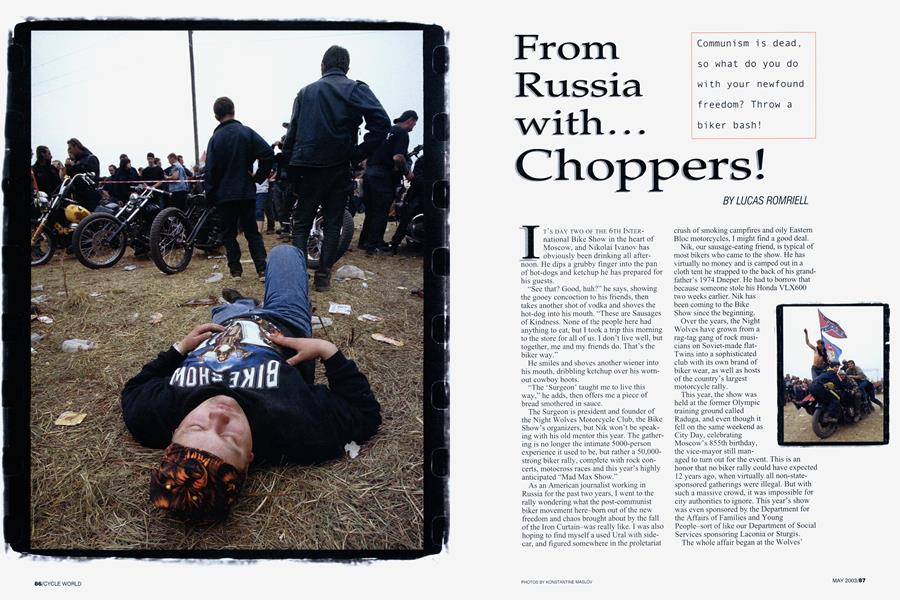

From Russia with... Choppers!

LUCAS ROMRIELL

Communism is dead, so what do you do with your newfound freedom? Throw a biker bash!

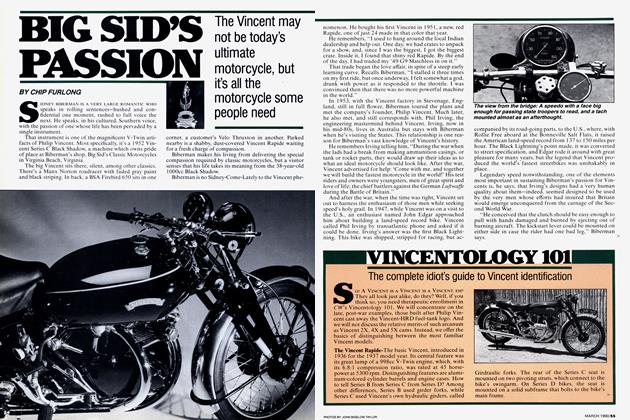

IT'S DAY TWO OF THE 6TH INTERnational Bike Show in the heart of Moscow, and Nikolai Ivanov has obviously been drinking all afternoon. He dips a grubby finger into the pan of hot-dogs and ketchup he has prepared for his guests.

“See that? Good, huh?” he says, showing the gooey concoction to his friends, then takes another shot of vodka and shoves the hot-dog into his mouth. “These are Sausages of Kindness. None of the people here had anything to eat, but I took a trip this morning to the store for all of us. I don’t live well, but together, me and my friends do. That’s the biker way.”

He smiles and shoves another wiener into his mouth, dribbling ketchup over his wornout cowboy boots.

“The ‘Surgeon’ taught me to live this way,” he adds, then offers me a piece of bread smothered in sauce.

The Surgeon is president and founder of the Night Wolves Motorcycle Club, the Bike Show’s organizers, but Nik won’t be speaking with his old mentor this year. The gathering is no longer the intimate 5000-person experience it used to be, but rather a 50,000strong biker rally, complete with rock concerts, motocross races and this year’s highly anticipated “Mad Max Show.”

As an American journalist working in Russia for the past two years, I went to the rally wondering what the post-communist biker movement here-born out of the new freedom and chaos brought about by the fall of the Iron Curtain-was really like. I was also hoping to find myself a used Ural with sidecar, and figured somewhere in the proletariat crush of smoking campfires and oily Eastern Bloc motorcycles, I might find a good deal.

Nik, our sausage-eating friend, is typical of most bikers who came to the show. He has virtually no money and is camped out in a cloth tent he strapped to the back of his grandfather’s 1974 Dneper. He had to borrow that because someone stole his Honda VLX600 two weeks earlier. Nik has been coming to the Bike Show since the beginning.

Over the years, the Night Wolves have grown from a rag-tag gang of rock musicians on Soviet-made flatTwins into a sophisticated club with its own brand of biker wear, as well as hosts of the country’s largest motorcycle rally.

This year, the show was held at the former Olympic training ground called Raduga, and even though it fell on the same weekend as City Day, celebrating Moscow’s 855th birthday, the vice-mayor still managed to turn out for the event. This is an honor that no biker rally could have expected 12 years ago, when virtually all non-statesponsored gatherings were illegal. But with such a massive crowd, it was impossible for city authorities to ignore. This year’s show was even sponsored by the Department for the Affairs of Families and Young People-sort of like our Department of Social Services sponsoring Laconia or Sturgis.

The whole affair began at the Wolves’ headquarters on the outskirts of Moscow, Biker Center (see sidebar). About 300 riders showed up, the stated goal creating a single column of riders for the 30-mile journey to the show. Moscow police on BMW K-bikes or driving Ladas tried to keep other traffic at bay long enough for the riders to form up at the scheduled hour of 2 p.m. But there was no success, because now that the government is in such disarray, few Russian drivers fear the police. Even fewer fear bikers. Russia didn’t have The Wild One or the Hell’s Angels to build a negative stereotype.

Vasi ilk, Honda Mag thing bad very good somewhere a lanky 2®-year-oid, na. "I'm Russian, so about our bikes, but ," he says. "For once, and not have anything dreams of I shouldn' they real I'd like b r e a k." buying a t say any ly aren't to go

So it didn’t take long for the cages to bust up the column, and not much longer for the highway to become a total freefor-all, with motorcyclists cutting through traffic, running stoplights and riding down the sidewalk in an effort to catch

up with the leader of the pack.

Whatever their route to the grounds, at least half the participants were under 25 and showed up on kludgedtogether Russian bikes that had been chopped, tuned, tricked-out, jerry-rigged or were just barely running. The roads into Moscow were lined with riders trying to kick-start their Urals and Dnepers, or pushing their Izh Planeta 5 s (horribly smoky 500cc commuter bikes) to the next gas station, while the few riders on new Japanese and European bikes-a small but growing segment are able to afford such luxurious mounts-cruised smoothly past.

There were, however, no bikes trailered to this event.

Even Galina Ivanova, a heavyset 70-year-old woman, battled her way past the Mercedes jeeps and rundown Ladas on Moscow’s treacherous roads, riding her 10-year-old Chinese scooter to reach the show. The crowd later voted her “Miss Most Beautiful Viewer” with their applause.

At her age, the esteemed Mrs. Ivanova was the exception,

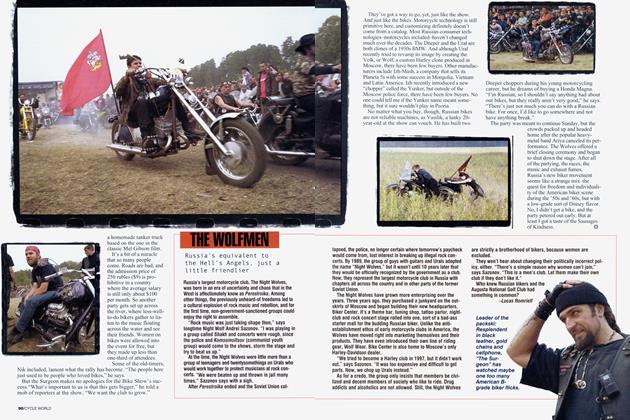

for most bikers were little more than young adrenaline junkies. Take a 17-year-old young lady I met named Yoga. She showed up on a used 400cc Suzuki Bandit bought this summer with the money she earned from her job as a go-go dancer in a nightclub.

“People think if you’re a girl and you ride that you’re vulgar and irresponsible. They say it’s a man’s job,” she says defiantly. But nothing, not even her parents’ pleas, was enough to keep Yoga from buying a bike. “My mother knew she couldn’t stop me,” she says, taking a drag off her cigarette. “She even gave me a little money for the bike.” Probably if Mom saw how things were going at the show, she would have regretted the contribution. By the middle of day two, the field in front of the stage where the shows and contests were held looked like a garbage dump filled with empty 2-liter plastic beer bottles and the bodies of passedout partiers.

An 11 a.m. wake-up call came in the form of a heavy-metal music concert, followed by an Open-class motocross race. The latter was total chaos as riders on everything from 250cc enduros to 500cc quads raced around to a recorded soundtrack of adrenaline-pumping punk rock.

Unfortunately, there weren’t enough guards to keep the fans under control and people kept dashing across the track, narrowly avoiding being hit by the racers. Andrei Sazonov, a longtime Night Wolf in charge of supervising the race, just laughed at the confusion. When asked why they didn’t keep the attendees under better control, he just smiled and gave the classic Russian response: “It’s normal.”

So, as you might expect, the other bike contests were also a poorly coordinated fiasco. Security guards pushed everyone and their machines into a big square around an outdoor boxing ring, set up a table for the judges and told the contestants to start riding. By far the day’s most popular contest was the “Riding a Sidecar With the Most People,” won by a young man on a Dneper with a load of 20 inebriants.

The “Crazy Bike” prize was awarded to something called M-Style, a gigantic, custom-made “sportbike” built around an equally giant eight-cylinder Gaz-54 truck engine.

Yoga, the young go-go dancer I met earlier, was limping following a drunken fall from her bike and sadly was unable to compete in the “Miss Bike Show” competition.

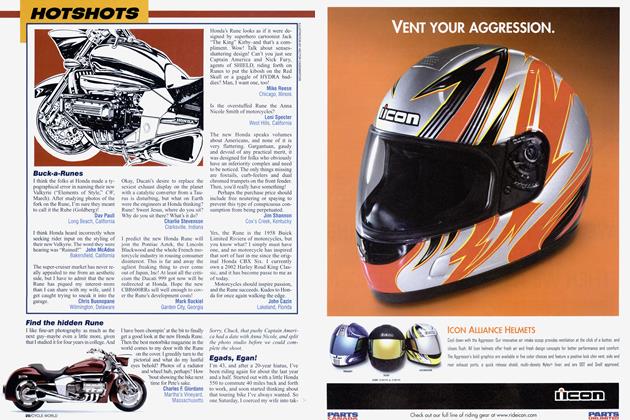

The climax for all this chaos was the 30-minute “Mad Max” production, written and directed by the Surgeon himself. With all the money the Wolves have made from the bike show and other endeavors, the entertainment was more advanced than ever. Which isn’t to say it’s actually very advanced at all, because the Mad Max thing was really little more than fireworks and people cutting donuts on dirtbikes, finished off by an awkwardly choreographed battle on top of a homemade tanker truck based on the one in the classic Mel Gibson film. It's a bit of a miracle that so many people come. Roads are bad, and the admission price of 250 rubles ($9) is pro hibitive in a country where the average salary is still only about $100 per month. So another party gets set up across the river, where less-wellto-do bikers gather to lis ten to the music floating across the water and see their friends. Women on bikes were allowed into the event for free, but they made up less than one-third of attendees. Some of the old-timers, Nik included, lament what the rally has become. "The people here just used to be people who loved bikes," he says. But the Surgeon makes no apologies for the Bike Show's suc cess."What's important to us is that this gets bigger," he told a mob of reporters at the show, "We want the club to grow." They’ve got a way to go, yet, just like the show. And just like the bikes. Motorcycle technology is still primitive here, and customizing definitely doesn’t come from a catalog. Most Russian consumer technologies-motorcycles included-haven’t changed much over the decades. The Dneper and the Ural are both clones of a 1930s BMW. And although Ural recently tried to revamp its image by creating the Volk, or Wolf, a custom Harley clone produced in Moscow, there have been few buyers. Other manufacturers include Izh-Mash, a company that sells its Planeta 5s with some success in Mongolia, Vietnam and Latin America. Izh recently introduced a new “chopper” called the Yunker, but outside of the Moscow police force, there have been few buyers. No one could tell me if the Yunker name meant something, but it sure wouldn’t play in Peoria.

No matter what you buy, though, Russian bikes are not reliable machines, as Vasilik, a lanky 20year-old at the show can vouch. He has built two Dneper choppers during his young motorcycling career, but he dreams of buying a Honda Magna. “I’m Russian, so I shouldn’t say anything bad about our bikes, but they really aren’t very good,” he says. “There’s just not much you can do with a Russian bike. For once, I’d like to go somewhere and not have anything break.”

The party was meant to continue Sunday, but the crowds packed up and headed home after the popular heavymetal band Ariya canceled its performance. The Wolves offered a brief closing ceremony and began to shut down the stage. After all of the partying, the races, the music and exhaust fumes,

Russia’s new biker movement seems like a strange mix-the quest for freedom and individuality of the American biker scene during the ’50s and ’60s, but with a low-grade sort of Disney flavor. No, I didn’t get a bike, and the party petered out early. But at least I got a taste of the Sausages of Kindness. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue