SERVICE

Paul Dean

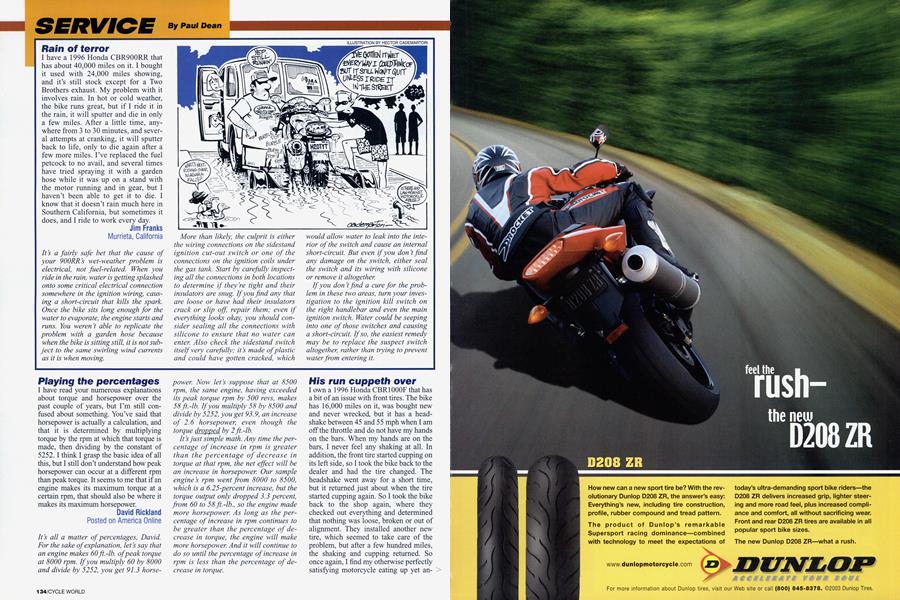

Rain of terror

I have a 1996 Honda CBR900RR that has about 40,000 miles on it. I bought it used with 24,000 miles showing, and it’s still stock except for a Two Brothers exhaust. My problem with it involves rain. In hot or cold weather, the bike runs great, but if I ride it in the rain, it will sputter and die in only a few miles. After a little time, anywhere from 3 to 30 minutes, and several attempts at cranking, it will sputter back to life, only to die again after a few more miles. I’ve replaced the fuel petcock to no avail, and several times have tried spraying it with a garden hose while it was up on a stand with the motor running and in gear, but I haven’t been able to get it to die. I know that it doesn’t rain much here in Southern California, but sometimes it does, and I ride to work every day.

Jim Franks Murrieta, California

It ’s ci fairly safe bet that the cause of your 900RR’s wet-weather problem is electrical, not fuel-related. When you ride in the rain, water is getting splashed onto some critical electrical connection somewhere in the ignition wiring, causing a short-circuit that kills the spark. Once the bike sits long enough for the water to evaporate, the engine starts and runs. You weren’t able to replicate the problem with a garden hose because when the bike is sitting still, it is not subject to the same swirling wind currents as it is when moving.

More than likely, the culprit is either the wiring connections on the sidestand ignition cut-out switch or one of the connections on the ignition coils under the gas tank. Start by carefully inspecting all the connections in both locations to determine if they’re tight and their insulators are snug. If you find any that are loose or have had their insulators crack or slip off repair them; even if everything looks okay, you should consider sealing all the connections with silicone to ensure that no water can enter. Also check the sidestand switch itself very carefully; it’s made ofplastic and could have gotten cracked, which would allow water to leak into the interior of the switch and cause an internal short-circuit. But even if you don’t find any damage on the switch, either seal the switch and its wiring with silicone or remove it altogether.

If you don’t find a cure for the problem in these two areas, turn your investigation to the ignition kill switch on the right handlebar and even the main ignition switch. Water could be seeping into one of those switches and causing a short-circuit. If so, the easiest remedy may be to replace the suspect switch altogether, rather than trying to prevent water from entering it.

Playing the percentages

I have read your numerous explanations about torque and horsepower over the past couple of years, but I’m still confused about something. You’ve said that horsepower is actually a calculation, and that it is determined by multiplying torque by the rpm at which that torque is made, then dividing by the constant of 5252.1 think I grasp the basic idea of all this, but I still don’t understand how peak horsepower can occur at a different rpm than peak torque. It seems to me that if an engine makes its maximum torque at a certain rpm, that should also be where it makes its maximum horsepower.

David Rickland Posted on America Online

It’s all a matter of percentages, David. For the sake of explanation, let ’s say that an engine makes 60 ft.-lb. of peak torque at 8000 rpm. If you multiply 60 by 8000 and divide by 5252, you get 91.3 horsepower. Now let’s suppose that at 8500 rpm, the same engine, having exceeded its peak torque rpm by 500 revs, makes 58 ft.-lb. If you multiply 58 by 8500 and divide by 5252, you get 93.9, an increase of 2.6 horsepower, even though the torque dropped by 2 ft.-lb.

It’s just simple math. Any time the percentage of increase in rpm is greater than the percentage of decrease in torque at that rpm, the net effect will be an increase in horsepower. Our sample engine’s rpm went from 8000 to 8500, which is a 6.25-percent increase, but the torque output only dropped 3.3 percent, from 60 to 58 ft.-lb., so the engine made more horsepower. As long as the percentage of increase in rpm continues to be greater than the percentage of decrease in torque, the engine will make more horsepower. And it will continue to do so until the percentage of increase in rpm is less than the percentage of decrease in torque.

His run cuppeth over

I own a 1996 Honda CBR1000F that has a bit of an issue with front tires. The bike has 16,000 miles on it, was bought new and never wrecked, but it has a headshake between 45 and 55 mph when I am off the throttle and do not have my hands on the bars. When my hands are on the bars, I never feel any shaking at all. In addition, the front tire started cupping on its left side, so I took the bike back to the dealer and had the tire changed. The headshake went away for a short time, but it returned just about when the tire started cupping again. So I took the bike back to the shop again, where they checked out everything and determined that nothing was loose, broken or out of alignment. They installed another new tire, which seemed to take care of the problem, but after a few hundred miles, the shaking and cupping returned. So once again, I find my otherwise perfectly satisfying motorcycle eating up yet an> other expensive front tire. Any suggestions? This is driving me nuts!

Jeff Phillips Posted on America Online

I wish I had good news for you, but I don’t. Many motorcycles suffer from a hands-off headshake between 40 and 60 mph, and quite a few cause their front tires to cup as they wear. The cupping usually appears on the left side of the tire before the right because we ride on the right side of the road in the U.S. Most roads are crowned, so even when a bike is going straight ahead, the tires ’ contact patches are slightly to the left of center. Plus, riding on the right side of the road also means that we tend to take left-hand turns faster than right-handers, simply because any given left-hand turn has a longer radius than its right-hand opposite, and because we usually can see farther around them.

Making matters even worse for you is the fact that the CBR1000F was notorious for rapid front-tire wear. Once, during an Open-class shootout, our test CBR wore out its front tire completely in a day-and-a-half of riding totaling less than 1000 miles, all on public roads. As the tire wore, the cupping on both sides got so severe that our testers could feel the tire bumping along the pavement, much like with a knobby tire, any time they made a sharp, low-speed turn in a parking lot or gas station. Some brands or models of tires might give slightly longer relief than others when new, but Fm afraid that unless you re ready to undertake a complete front-end redesign, you ’re stuck with what you’ve got.

Car vs. bike

Have you ever considered writing about the differences between cars and motorcycles? In particular, I am interested in the reasons a bike engine can rev two or three times higher than a car engine and still be reliable. Any help you could offer dealing with other differences between the two types of vehicles would be appreciated. Dave Califano

Brooklyn, New York

Geez, Dave, could you be any less specific? Aside from the more obvious differences between motorcycles and cars (two wheels vs. four, handlebars vs. steering wheels, you ride on the inside of one and the outside of the other, etc.), Fm not sure what you’re after here. But as far as the differences in maximum engine rpm are concerned, several factors dictate those limits, the most critical being piston speed, measured in feet per minute (fpm). If piston speeds exceed a certain fpm limit, the engine’s reciprocating components (pistons, rods, wristpins, etc.) are put at great risk of pulling themselves apart. Whether in cars or motorcycles, today ’s street engines, which are expected to have a long and trouble-free life, generally are designed so that piston speed won’t exceed about 4000 fpm. Many racing engines, which have much shorter life expectancies, extend that ceiling up to and slightly beyond 5000. Topfuel and other high-end drag-racing engines, which often only have to survive for a matter of seconds, can reach piston speeds in excess of 6000 fpm-but not often, and not for long.

The two factors that dictate piston speed are engine rpm and piston stroke. The shorter the stroke, the lower the piston speed will be at any given rpm. Thus, the primary reason motorcycle engines can operate safely in much higher rpm ranges than cars is that they are smaller in displacement and have much shorter strokes. While the vast majority of car engines have strokes ranging from between 3 and 4!/4 inches, most motorcycle engines (those in the highperformance, high-rpm models, anyway) have strokes that range from around l5/s to just over 2 inches. With such tiny strokes, these engines can rev up to and beyond 13,000 or 14,000 rpm without coming apart. Many other motorcycle engines, however, including the HarleyDavidson Big Twins, have stroke dimensions equivalent to those of big-inch V-Eight car engines, which is why they also have comparable rpm limits. Several other factors-such as valvetrain weight and mass-contribute to an engine’s maximum rpm potential, but piston speed is the first and foremost.

It’s a blinking miracle

My 1997 Harley-Davidson Dyna Wide Glide has had a problem since a year after I bought it new. While I’m riding, one of the turnsignals will start blinking all on its own. Sometimes it’s the right signal, sometimes the left, sometimes both. Sometimes they will quit and refuse to work altogether. This doesn’t happen every time I ride the bike or only when it rains; it’s entirely unpredictable. Once the blinking or inoperation begins, it will continue until I stop, shut the engine off and restart it, after which the signals will function normally againfor a while. I’ve had the bike to two different dealers several times but the problem persists. One dealer told me that the cause might be a bad relay that costs more than a hundred dollars, and the other dealer says there is no relay in that year Wide Glide. What should I do?

Craig A. Ellis Frederick, Maryland

Actually, both dealers may be correct, and their disagreement could just be a> matter of terminology. There indeed is no turnsignal “relay” on your Wide Glide, but there is a turnsignal “module,” which is a small microprocessor that regulates the operation of the signals. And yes, it does cost more than $100. Every time one of the turnsignal buttons is depressed, the module activates the designated signal while it also begins a countdown process that determines how long the signal continues flashing. The module gets input from the speedometer, and the duration of the flashing is dictated by the distance the bike travels while the signal is in operation.

On any other bike besides a Harley and a BMW, the problem you describe might possibly be caused by the lone turnsignal switch on the left handlebar, which controls the operation of both the right and left signals; but on those two brands, the left and right switches are separate. And the chances of the same condition cropping up in both on your Harley are astronomical. Which leads me to believe that the problem is in the module. It’s a sealed unit, so you can’t take it apart; and while the factory service manual describes a troubleshooting process that can detect problems, it’s not likely to diagnose an intermittent problem such as yours.

So, as irrational as it might sound, the best troubleshooting procedure is to replace the module with one of a known value-either a brand-new one, which you no doubt would have to buy, or one from another bike that you would borrow just long enough to determine if the problem continues. Even the factory manual suggests making such a temporary swap if all the other troubleshooting steps have failed to identify any trouble areas in the module.

Prime time

I put my 1995 Triumph Trident back on the road after a year in the barn (my bad).

I didn’t expect such a long hibernation, so I failed to prepare the bike (my bad #2). I pulled the petcock assembly from the tank to speed up the gas-draining process. No problems starting up with fresh gas in the tank and a new battery, but it died not long after I closed the choke. It restarted only by using the “Prime” circuit on the petcock and will stay running only in that position. When riding, it sometimes needs a couple of switches to Prime to keep from running out of gas. This usually happens once a tankful, but sometimes not. Other than that, it burbles a bit when I close the throttle while riding. Any ideas about what’s wrong? The closest Triumph shop is more than an hour away.

Paul Cheramie Slidell, Louisiana

Your Triumph may have two different problems at work, both of them resulting from its year of cold storage. The bike has a vacuum-operated petcock that, when in the On or Reserve positions, allows fuel to flow only when intake-manifold vacuum pulls a diaphragm-controlled shutoff valve away from its seat. But when the petcock is switched to Prime, the diaphragm valve is bypassed and fuel can flow into the carbs just as it would with a non-vacuum petcock. Your description of the symptoms tells me that when on either of the vacuum-controlled settings, the petcock valve is hanging up and not allowing the valve to open either fully or at all. This could be caused by gummy residue in the petcock that resulted from the bike sitting unused-and unprepared-for so long. Or perhaps the rubber vacuum hose that leads from the intake manifold to the petcock is cracked or plugged, either of which would hamper the operation of the vacuum valve. You need to check the hose and disassemble the petcock for a good cleaning, after which the engine should continue running without the need to switch to Prime.

If the engine still burbles on trailing throttle after the petcock is fully operational, the bike’s hibernation may also have slightly gummed up the pilot jets in the carburetors. To remedy that condition, you ’ll need to pull the carbs and give them a thorough cleaning, making sure to remove any residue that might have collected inside the very small orifices in the pilot jets. And if you can’t successfully clean the jets, well, they’re cheap; just replace them. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find reasonable solutions in your area? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail your inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com: or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com and click on the Feedback button. Please, always include your name, city and state of residence. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but do include enough information about the problem to permit a rational diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we can’t guarantee a reply to every question.