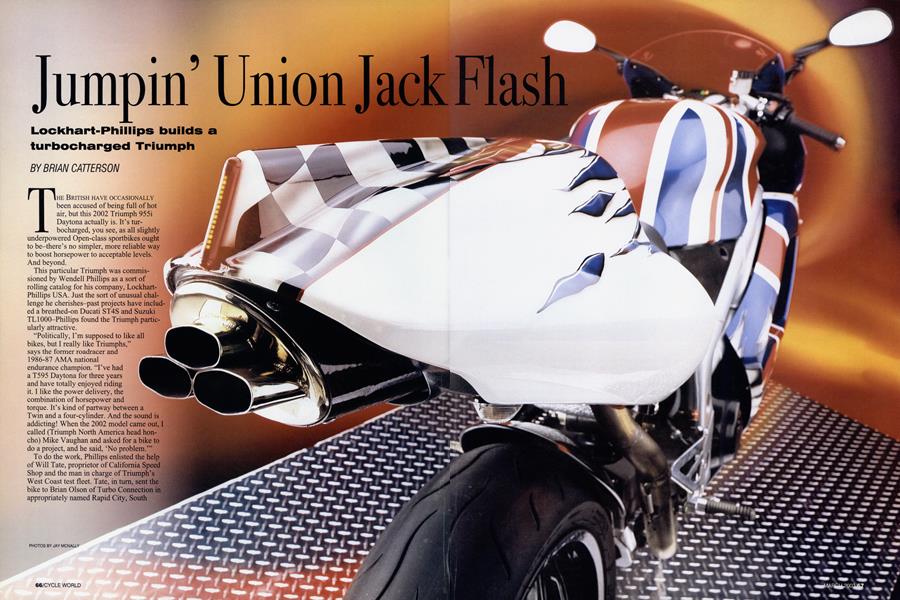

Jumpin' Union Jack Flash

Lockhart-Phillips builds a turbocharged Triumph

BRIAN CATTERSON

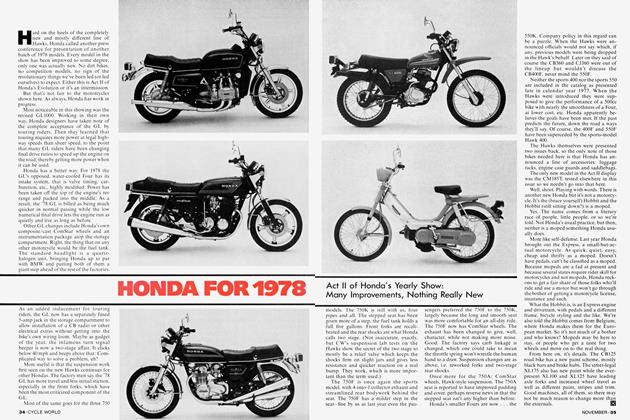

THE BRITISH HAVE OCCASIONALLY been accused of being full of hot air, but this 2002 Triumph 955i Daytona actually is. It's turbocharged, you see, as all slightly underpowered Open-class sportbikes ought to be-there’s no simpler, more reliable way to boost horsepower to acceptable levels. And beyond.

This particular Triumph was commissioned by Wendell Phillips as a sort of rolling catalog for his company, LockhartPhillips USA. Just the sort of unusual challenge he cherishes-past projects have includ ed a breathed-on Ducati ST4S and Suzuki TLIOOO-Phillips found the Triumph particularly attractive.

“Politically, I’m supposed to like all bikes, but I really like Triumphs,” says the former roadracer and 1986-87 AMA national endurance champion. “I’ve had a T595 Daytona for three years and have totally enjoyed riding it. I like the power delivery, the combination of horsepower and torque. It’s kind of partway between a Twin and a four-cylinder. And the sound is addicting! When the 2002 model came out, I called (Triumph North America head honcho) Mike Vaughan and asked for a bike to do a project, and he said, ‘No problem.’”

To do the work, Phillips enlisted the help of Will Tate, proprietor of California Speed Shop and the man in charge of Triumph’s West Coast test fleet. Tate, in turn, sent the bike to Brian Olson of Turbo Connection in appropriately named Rapid City, South Dakota. A man with considerable experience turbocharging Triumphs, he talks excitedly about “sleeper” Sprint STs and Tigers yanking the mirrors off of GSX-R 1000s and Rls!

What’s unique about the Turbo Connection setup is its Aerocharger turbo. Turbochargers work by using the normally wasted exhaust-gas pressure to spin a turbine that in turn compresses the air entering the intake tract. Ordinarily, there is a bit of lag at low rpm, when exhaust-gas velocity isn’t sufficient to get the turbine spinning. Aerocharger gets around this by employing “variable vanes,” pivoting winglets that effectively close off the area around the turbine at low rpm, concentrating the gases on the turbine itself.

Then, at higher revs, the vanes open up, allowing excess exhaust-gas pressure to pass straight through, thereby maintaining the same level of boost. There is no waste gate as on a traditional turbo. The result is turbo boost from as low as 2500 rpm, as opposed to the usual 4000 rpm required by traditional turbos. A spring sets the desired boost, and a two-position pneumatic switch changes it between two predetermined settings, in this case 6.5 and 8.5 psi. A self-contained oiling system uses a wick to lube the ultra-lowfriction turbine bearings, rather than replumbing the engine’s oiling system as on other brands.

The other interesting component is the air-to-air intercooler located behind the Daytona’s steering head. This looks like your typical radiator or oil cooler, but instead cools incoming air heated by the fast-spinning (100,000 rpm!) turbo and exhaust gases as it flows to the stock Keihin throttle bodies. Turbo Connection installed a thicker head gasket to lower compression from the stock 12.1 to 11:1, and then plugged in its own engine manager that piggybacks onto the stock Sagem ECU. Cost of this whole setup is $5999, labor not included.

With the bike back in Southern California, Tate got busy putting on the finishing touches. First the exhaust, a threepart affair consisting of a header made by Turbo Connection, a custom mid-section made by Mark’s Pipes in Hesperia, California, and an Akrapovic muffler with a trick, tri-trip endcap (it’s a Triple, you know) fabbed by The Fab Shop in Irvine.

The chassis got its share of attention, too. First addition was a single-sided swingarm off a 2001 Daytona, added because it has more “personality” than the ’02’s doublesided job and adds .75-inch to the wheelbase. Attack Racing provided the rearsets, the four-point shock linkage that replaces the ’01 swingarm’s three-pointer, as well as a set of triple-clamps with less offset for more trail-all items developed through the firm’s experience racing Daytonas in the AMA Pro Thunder Series. A Penske shock, RaceTech-modified fork with Progressive springs, Marvic Penta wheels, Brembo front brakes, billet-aluminum hubcaps from South Bay Triumph and every carbon-fiber component in the Lockhart-Phillips catalog complete the parts list.

Covering everything up is a fairing and custom tailpiece made by AK Composites in Huntington Beach, based on Tate’s cardboard-and-masking-tape mock-up. Tate calls the vertical tail a “Cadillac Fin,” but the way this bike works and (especially) sounds, we imagined it as one of those yawcontrol wings used by the Penske Indycars a few years back. A Radiantz LED taillight caps off the fin, while Lockhart halogen tumsignals and brake lights from the local Pep Boys reside along with the license plate under the rear fender.

Crowning glory is the Union Jack paint scheme, sprayed by Aaron Hagar, son of “Red Rocker” Sammy Hagar, and dedicated to Simon Clarke, a filmmaker friend of Phillips who lost his life last year in a motorcycle accident.

“Simon was preparing a one-hour documentary on sportbiking, and was just about finished with it when he hit a sheriffs truck that was stopped on Glendora Mountain Road,” Phillips recalls. “He was a very unlikely guy to have been killed on the street, because he was all about taking it to the track.”

British-born, Clarke’s casket was draped with the Union Jack at his funeral, which was the inspiration for the turbo Triple’s paint scheme.

But enough of the sad stuff, because one ride on this bike is sure to put a smile on your face. A sadistic, sideways sort of smile, like an escaped lunatic might wear, but a smile nonetheless.

Riding around town at the Mild boost setting, where the motor makes a paltry 160 horsepower, you could almost be convinced it’s stock. Tate, in fact, accompanied a group of journalists on a press intro with the Daytona wearing its stock bodywork and muffler, and no one noticed until the afternoon, when he went wheelying past the lot of them at 120 mph! Talk about a sleeper...

Once you’ve switched to the Wild setting, though, the first position become pointless, because there’s no going back. Suddenly you’re an adrenaline junkie craving the next hit of acceleration. And we’re not talking stoplight-to-stoplight stuff, either: Tate warned me not to give the bike full-stick in first or second gear, and indeed, doing so proved to be flirting with disaster as the entire bike attempted to rotate around its rear tire. Safer to short-shift through first and second, then whack it on in third, where even brief applications of throttle see the digital speedo leap to 120 mph-plus! It’s not so much the acceleration that gets to you as the acceleration combined with the speed; this thing accelerates as hard in fourth as a GSX-R1000 does in second, always accompanied by that telltale turbo whoosh! Addicting stuff.

But that acceleration is a double-edged sword, because while you can get up to ludicrous speeds in an incredibly short amount of time, you also cover a lot of ground. As a result, entire cities shrink in size, time and space folding into one another like some sort of sci-fi movie. Hold it on long enough and you’d probably pass yourself in another dimension!

Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising, considering that peak rear-wheel output has jumped to 177.3 horsepower and 115.9 foot-pounds of torque-gains of 52 bhp and 52 ft.-lbs. compared to the last 955i we tested. More impressive, though, is the depth of that output; the engine makes nearpeak horsepower from 8000 to 10,000 rpm, and near-peak torque from 6000 to 8000 rpm. There aren’t many bikes with curves that flat, especially with the sort of numbers we’re talking about here.

So yes, the British may be full of hot air, but this Britbike lives up to the talk. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

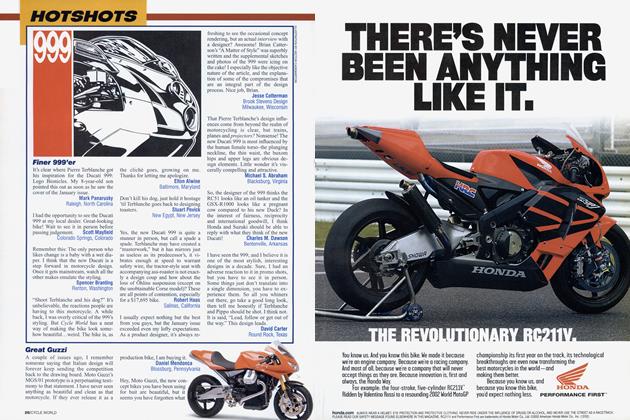

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

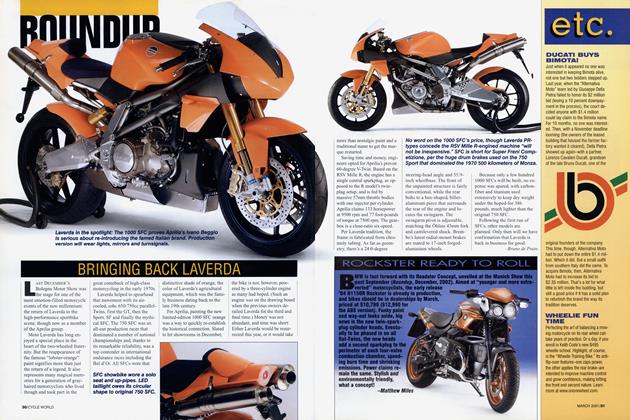

Roundup

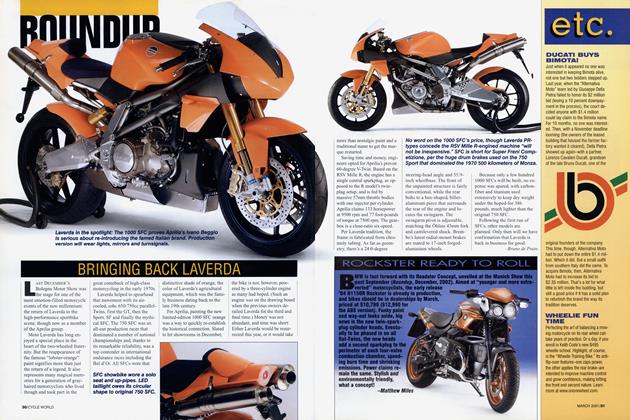

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles