Pass Masters

"ZFERROOO!” SHOUTED THE TIMEKEEPER. Uh, oh, what have I done now? “Zero, you got a 0.00,” he elaborated.

Inconceivable. Granted, I had begun to get a handle on this timekeeping thing, but all I was using was the second hand on my Tag Heuer. I’d have been happy to cross the finish line within a few seconds of my specified time, never mind nailing it to the hundredth of a second!

“Just dumb luck,” I told him.

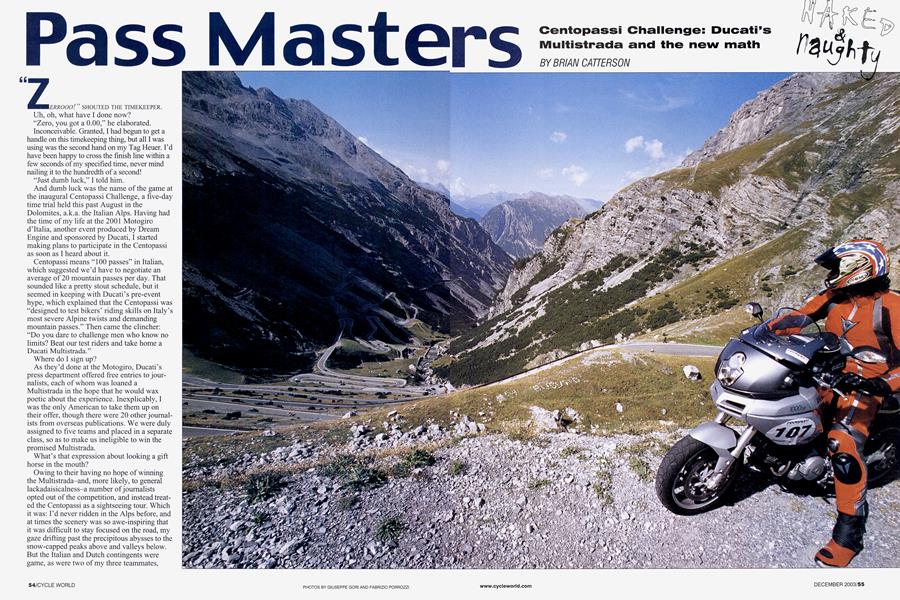

And dumb luck was the name of the game at the inaugural Centopassi Challenge, a five-day time trial held this past August in the Dolomites, a.k.a. the Italian Alps. Having had the time of my life at the 2001 Motogiro d’ltalia, another event produced by Dream Engine and sponsored by Ducati, I started making plans to participate in the Centopassi as soon as I heard about it.

Centopassi means “100 passes” in Italian, which suggested we’d have to negotiate an average of 20 mountain passes per day. That sounded like a pretty stout schedule, but it seemed in keeping with Ducati’s pre-event hype, which explained that the Centopassi was “designed to test bikers’ riding skills on Italy’s most severe Alpine twists and demanding mountain passes.” Then came the clincher:

“Do you dare to challenge men who know no limits? Beat our test riders and take home a Ducati Multistrada.”

Where do I sign up?

As they’d done at the Motogiro, Ducati’s press department offered free entries to journalists, each of whom was loaned a Multistrada in the hope that he would wax poetic about the experience. Inexplicably, I was the only American to take them up on their offer, though there were 20 other journalists from overseas publications. We were duly assigned to five teams and placed in a separate class, so as to make us ineligible to win the promised Multistrada.

What’s that expression about looking a gift horse in the mouth?

Owing to their having no hope of winning the Multistrada-and, more likely, to general lackadaisicalness-a number of journalists opted out of the competition, and instead treated the Centopassi as a sightseeing tour. Which it was: I’d never ridden in the Alps before, and at times the scenery was so awe-inspiring that it was difficult to stay focused on the road, my gaze drifting past the precipitous abysses to the snow-capped peaks above and valleys below. But the Italian and Dutch contingents were game, as were two of my three teammates, freelance journalist Toshihiro Wakayama of Japan and Robert Glück of Germany’s Motorrad PS magazine, whose last name literally translates as “luck.”

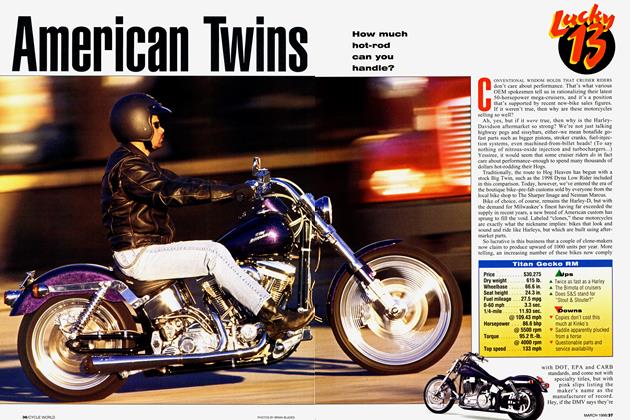

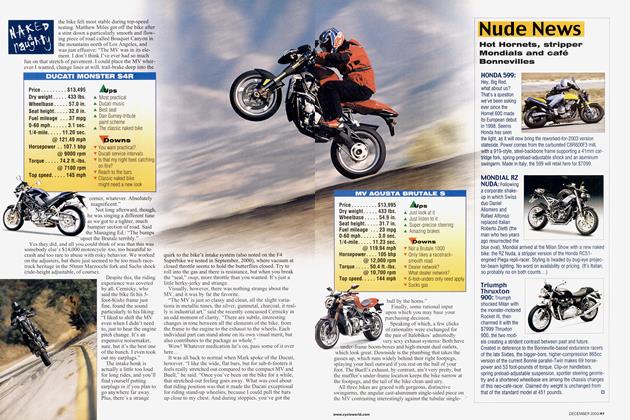

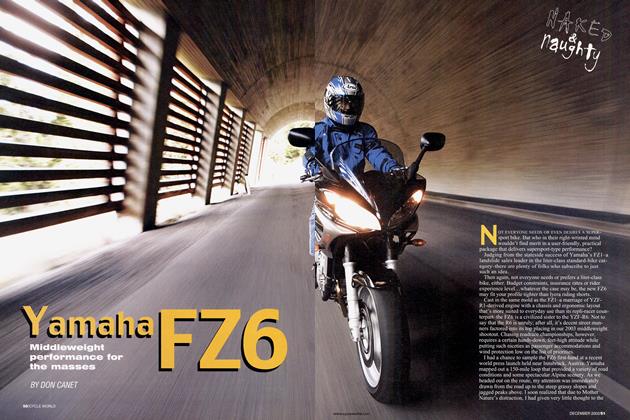

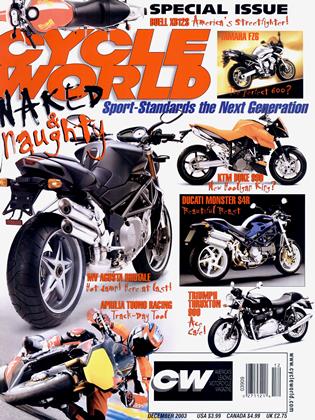

NAKED & naughty

Centopassi Challenge: Ducati’s Multistrada and the new math

BRIAN CATTERSON

Ducati thoughtfully provided an Italian guide for each team, and here again I got lucky. Joining our Team Pordoi (each squad was named

after one of the passes on our route) was Gianfranco Sulas, a Ducati press-fleet technician. Though none of us had ever met before, we became fast friends, not least because we rode at a similar pace-that is, fast-a product of our racing experience. Gianfranco is a diehard motocrosser, Robert had taken part in an endurance roadrace the previous weekend, and Toshi’s claim to fame is finishing 11th in the 1989 Japanese 250cc Grand Prix. Talk about an impressive resume!

The fact that the results would take the three best finishes from each team meant that Robert, Toshi and I had to be on our game all week if we wanted to win. (Gianfranco’s results didn’t count.) Unfortunately, Toshi didn’t immediately grasp the timekeeping, missed the first checkpoint leaving the Ducati factory and was scored as “unclassified” on Day One. Not an auspicious start.

Centoregolamenti

“One hundred regulations,” that’s how many there appeared to be in the thick Federazione Motociclistica Italiana rulebook we each received at sign-up Tuesday morning.

Fortunately for me, our hosts were the Motoclub Libero Liberati, the same folks who put on the Motogiro. So not only were there a few familiar faces (some of whom remembered me as “Ago Grande,” oh the humility...), but the timekeeping procedures were the same. Having come to understand this during the Motogiro, I had a definite advantage going in.

It’s really not that difficult. There are two kinds of checkpoints: a CO, for controllo orario or “hourly check,” where the time you break a light beam is noted to the hundredth of a second; and a CT, for controllo a timbro or “stamp check,” where you simply have to get your card stamped. The catch, which I recalled from the Motogiro, is that the last CO of the day is traditionally tough to make. Asking a few questions alerted us to the fact that you could get your card punched 5 minutes prior to the time noted on it at a CT, so if you went there with your helmet and gloves on and promptly got a move on, you got a head start on the subsequent CO section.

My suspicions were confirmed at the end of the day, when we arrived at the final CO in Lavarone (site of this year’s Trial des Nations) with less than 30 seconds to spare. Robert and Toshi had lower numbers than mine, which meant they had earlier arrival times, thus they were both more than a minute late.

Sure enough, when the day’s results were posted, I was listed as second in the Giornalisti class with a time of 5.59 seconds, which would have been good enough for fourth overall against the paying competitors. Marco Marini of Italy’s Motociclismo magazine was the firstplace journalist, thanks to his winning finish in the evening’s gymkhana.

Gymwhata? Precisely. Pre-race materials told of special tests at the end of each day, which had me dreaming about Europeanstyle hillclimbs and Supermoto courses laid out in vacant parking lots.

Dream on. These were more like the courses used in Buell Battletrax competitions, only tighter, and in addition to cones, bowling pins were used. Knock over a cone and you were docked 2 seconds, bowling pins cost you a second apiece.

I opted for a conservative first attempt and turned a time 4 seconds off the winner’s pace, albeit with no penalties. Some of the other competitors tried a bit harder. Most spectacular was twentysomething Steve Chidley of England’s Fast Bikes magazine, whose all-or-nothing approach saw him scatter more pins than a 7-11 split. Earlier in the day, we’d spotted Steve standing by the side of the autostrada covered in crankcase-breather oil from an overly ambitious wheelie. “It wasn’t that long, only about a half-mile,” he said with a straight face. I promptly nicknamed him “Squidly,” which fits right in with “Frosty,” “Shakey” and the other Fast Bikers I’d met over the years. I think it’ll stick.

Centopasti

“One hundred pastas,” that was the theme for Day Two. Considering that Day One was largely a transit stage, with two autostrada stints broken up by a run up the hill into historic Teolo, we were looking forward to some “real” Alpine riding today. And we got it-when we were riding, that is, because we spent most of Wednesday standing around checkpoints waiting for our numbers to come up. One time, after roosting down what seemed like a paved motocross track into Pergolese, we arrived at a checkpoint fully 90 minutes early. Mentioning this to the organizers, we were told that maybe we shouldn’t ride so fast, and besides, they had allotted this time for lunch. Except we’d already stopped for lunch! It was quickly becoming apparent that “100 passes” was a gross exaggeration, and we’d be lucky to do a third of that number. Oh well, when in Italy.. .how are the gnocchi today, anyway?

Fortunately, the pace picked up at the end of the day. But not too much: At the rider’s meeting, we’d been warned that there would be surprise checkpoints at which average speed would be calculated, and if you were going too fast, you’d get a warning. Get another and you’d be disqualified. So we were more than a little pleased to encounter the first such speed check shortly after we’d stopped for gas. If we hadn’t stopped, we’d have been busted for sure.

Speaking of which, we were periodically joined by representatives of the Bologna Police Department mounted on

BMW R1150RTs-much to Ducati’s dismay, because they used to ride Monsters. The problem was what to do when you came up behind a cop and found that he was going slower than you’d like to go-or in some cases, needed to go to stay on time. Should you pass him and risk getting a ticket?

Ha! This is Italy we’re talking about. Most of the time, the motor officer would look in his mirrors, see us coming and wick it up. Then, a few kilometers later, when he realized that he wasn’t getting away, he’d wave us by! You never see that in California...

Day Two ended with a spectacular climb of the Passo Di Gavia, atop which there was a CT. Here, we quickly got our timecards stamped, then set a blistering pace down the twisty road into Santa Caterina Valfurva for the final CO. And barely made it. Robert and I arrived with 8 minutes to spare, which would have been only 3 if we hadn’t taken advantage of the 5-minute rule. Most of the competitors didn’t, and were minutes late. This is where I scored my perfect 0.00, and combined with a gymkhana time just 2.59 seconds off, I was suddenly leading the Journalist class!

Robert actually won on the day, as did our team, but with his and Toshi’s penalties from the day before, they would be hard-pressed to challenge for the lead. From that point forward, they acted as my domestiques, a bicycle-racing term for the teammates who support their lead rider, though they have no possibility of winning themselves. But unlike some of the hearty souls we’d seen grunting their way up the Gavia, I didn’t have to pedal! Lance Armstrong, eat your heart out...

Centotornati

“One hundred returns,” or what the Italians call switchbacks, that’s how many there supposedly are on the Passo Delio Stelvio, our first obstacle Thursday morning.

Or second, in my case, because I stayed out too late with the Brits the night before and had great difficulty folding the road book into a shape small enough to fit into my tankbag’s map window this morning. Origami isn’t any fun with a hangover!

Fortunately, the crisp mountain air soon cleared my head. Which was a good thing, because today’s riding was truly epic. It started with a spirited climb of the Stelvio, at 9000 feet the second highest pass in Europe, whose hairpin comers are so tight that you have to set up in the opposite lane to carry any sort of speed past the apex. The view from the top must be seen to be believed, as the road folds back and forth upon itself as far as the eye can see, like a pair of mirrors reflecting one another. Truly dizzying.

The Passo Di Giovo was another highlight, starting out with a series of fun sweepers along a river bank before culminating in a fast climb up a mountainside. The Passo Pennes ended the day, the rocks and scmb bmsh there reminding me of Southern California’s Anza Borrego Desert, one of the CW staffs favorite test loops.

Although the riding was challenging, the timekeeping was fairly straightforward, and I ended up topping the Journalist class with a time of just .44 of a second, which incidentally would have been good enough for first overall on the day. Robert and Toshi tied for second with identical times of 1.56 seconds, and our Team Pordoi won again, finishing some 3 minutes ahead of the Italians’ Team Falzarego.

It was a great day of riding, one of the most memorable of my life, but our smiles wouldn’t last much longer. As we followed the Centro signs to the main square in Bolzano, where we spent the night, it started to rain. And it would only get heavier.

Centogoccie di pioggia

“One hundred raindrops,” except it was more like a hundredzillion.

Day Four began as one of those days where you think you just might get away without having to wear your rainsuit... until a couple of heavy droplets score direct hits on your faceshield and you decide you’d rather be safe than sorry.

The road book promised some more awesome riding today, including the climb up and over our team’s namesake, Passo Pordoi. But rain, fog, thunder and lightning dampened the proceedings, and at one point I nearly hydroplaned off the side of a mountain, the tires regaining traction milliseconds before 1 slammed into a guardrail. And then it snowed! For perhaps 20 miles, we were forced to ride in cars’ wheel tracks, carefully crossing the slush in between when we pulled out to pass. We had a schedule to stick to, after all...

Or at least we did until that afternoon, when arriving at a checkpoint we were informed that the remainder of Friday’s timekeeping had been cancelled.

This was supposed to be the longest day on our itinerary, 211 miles, with our hotel that night across the border in Slovenia, in the former Yugoslavia. Unfortunately, we never made it. First, we took a wrong tum and ended up at the Austrian border. Then, after retracing our steps, we found the turn we’d missed and got back on the right track, which ultimately took us up a narrow, dirty, leaf-strewn goat path called the Passo Di Cason Di Lanza. Here, motocrosser Giancarlo was in his element, and he soon left me behind. But rounding a comer, I encountered him stopped in the middle of the road. An Italian bodybuilder and his equally shapely girlfriend, who were participating in the “Iron Biker” (read: tourist) class, had parked their Voxan beside the road when they spotted a black-and-yellow lizard, and had subsequently caught it. It was a big sucker, too! They offered to take a photo of me holding it, but having lived in Arizona for three years, I have a healthy respect for potentially poisonous creatures, so declined.

Shortly thereafter, we encountered a long line of bikes coming the other way. Turns out a landslide had blocked the road, and an Aprilia RSV Mille rider had fallen and broken his ankle trying to ride around it. A Ducati ST4, a Multistrada and an ambulance had gotten stuck in the mud, as well.

As if all that wasn’t bad enough, it then started to rain harder, and it was getting prematurely dark due to the heavy cloud cover. Did I mention that I had a tinted visor? And we were still a long way from Slovenia, with no idea how to get there.

There were about 40 of us now, and we huddled under a gas station canopy poring over maps. We quickly figured out how to get to our destination via the autostrada, only to leam from a local that a bridge had collapsed, so we weren’t going that way, either.

It took a while, as things in Italy often do, but a new plan was formulated. We’d ride into the nearest town en masse, and with the Dream Engine and Ducati people working the phones, try to find lodging for the night. As we started down the road, though, the heavens opened up, the rain falling harder than I’d ever experienced. I tried riding with my visor open, but the raindrops pelted my eyes, and as I looked down, I saw a frog hop across the road. Now that’s wet! And so I faithfully followed the taillight of the bike ahead of me and hoped the rider didn’t run off the road. Which was a good bet, considering that it was Andrea Fomi, head of Ducati’s R&D department.

At 11:30 that night, I finally got to sleep, my new buddy Robert inches away on his side of the bed. Actually, there were two beds, but in typical European fashion they were butted together so the hotel could sell the room as a single or a double. I recited a one-liner from Planes, Trains and Automobiles‘Those aren’t pillows ¡’’-which, owing to the fact that we split a six-pack for dinner, had us laughing hysterically. Robert was a former exchange student at Annapolis, Maryland, so speaks perfect English. Far better than my German, and maybe even my English.

Centocoppe

“One hundred trophies,” that’s how many there appeared to be at the awards banquet that capped the event Saturday night.

The fifth and final day started off sort of surreal, as I went to breakfast barefoot in my rainsuit pants and a T-shirt and waited for word on whether we would continue to Cortina D’Ampezzo or return to Bologna. It took a while, but Ducati PR manager Bruno Mastroianni ultimately decided that we would press on. Fortunately, the rain had stopped, but considering that something like half of the 140 competitors had failed to make it to Slovenia, the organizers scratched the final day’s timekeeping stages and scheduled two gymkhanas for the afternoon. The riding might have been good this day, except for the fact that Bruno was leading us to our destination in a car. Which was all right by me, because the roads were a mess from the record rainfall the night before, in which, the papers reported, two people had been killed and dozens injured when their hotel collapsed. As for us, a few riders had gone down unhurt, everyone had stories of trees in the road and cars spinning out, and the Brits said they’d even seen cattle being swept down a river!

After riding through Armageddon the previous day, the finish in Cortina was a bit anti-climactic, but we had a leisurely lunch, checked out the cars from the Maserati Club (whose rally also was ending here) and took part in the two gymkhanas, in which I dropped just 1.81 seconds. We then adjourned to our hotel rooms to primp for the gala awards banquet.

There, Ducati MotoGP rider Loris Capirossi presented the winner, Alberto Pignat of Italy, with the keys to the coveted Multistrada, custom-painted with the Centopassi logo overlaid on an alpine vista. The Honda CB1000 rider dropped just 8.5 seconds all week.

As for the Journalist competition, the Italian team won with a total score of 174 points, while we finished a close second with 170 points-if Toshi hadn’t missed the first checkpoint, we’d have won easy. I took solace in the fact that I topped the individual rankings, having dropped just 10.87 seconds.

The winners in each of the various categories received neat trophies made up of various Multistrada parts, but there were no trophies for the second-placed Journalist team. Nor, apparently, for the winning individual Journalist, until Ducati’s David Gross took pity on me and called me up onto the podium to present me with a leftover “Press Team” trophy.

So, I didn’t win a Multistrada, but I do have a nice pair of mufflers now. If I keep at this long enough, maybe I can build a complete bike... U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue