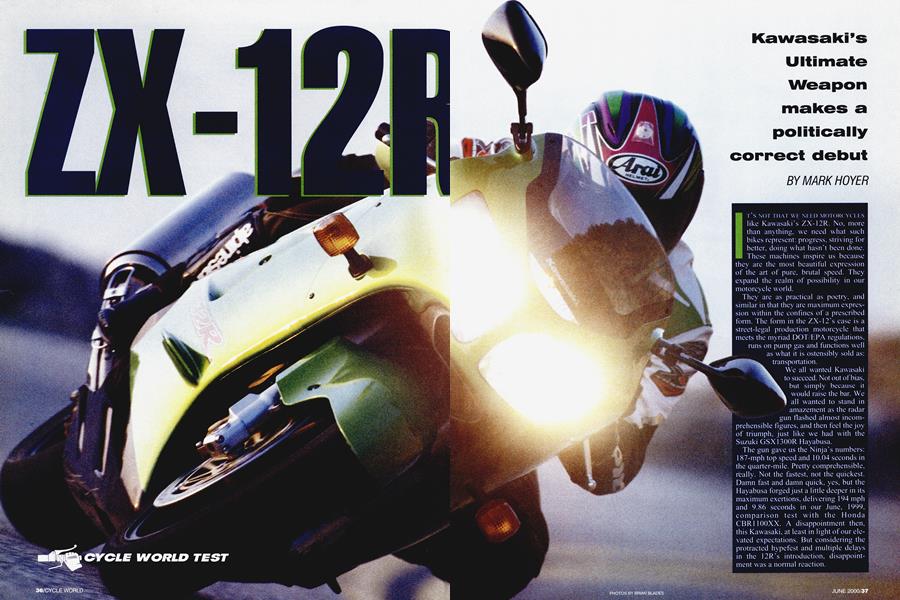

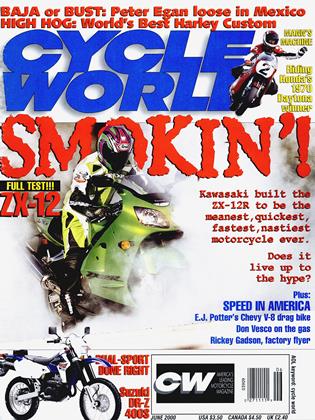

ZX-12R

CYCLE WORLD TEST

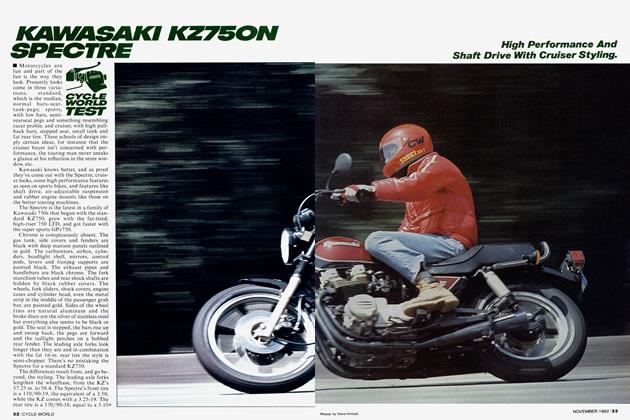

Kawasaki's Ultimate Weapon makes a politically correct debut

MARK HOYER

IT NOT THAT WE NEED MOTORCYCLES like Kawasaki's ZX-12R. No, more than anything, we need hat such bikes represent: progress, striving br better, doing what hasn't been done. These machines inspire us because they are the most beautiful expression of the art of pure. brutal speed. They expand the realm of possibility in our motorcycle world.

They are as practical as poetry, and similar in that they arc maximum exprcsSIOFI \\!thifl the confines of a prescribed form. The form in the ZX12's case is a street-legal production motorcycle that meets the myriad [)OT/E I~A regulations. runs on pump gas and tunctions vell as what it is ostensibly sold as: transportat I 011.

Ve all wanted Kawasaki to succeed. Not out of bias. but simply because it would raise the bar. We all wanted to stand in amazement as the radar uii flashed almost incomprehensible figures, and then feel the joy of triumph, just like we had with the Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa.

The gun gave us the Ninja’s numbers: 187-mph top speed and 10.04 seconds in the quarter-mile. Pretty comprehensible, rfeally. Not the fastest, not the quickest. Damn fast and damn quick, yes, but the Hayabusa forged just a little deeper in its maximum exertions, delivering 194 mph and 9.86 seconds in our June, 1999, comparison test with the Honda CBR1100XX. A disappointment then, this Kawasaki, at least in light of our elevated expectations. But considering the protracted hypefest and multiple delays in the 12R’s introduction, disappointment was a normal reaction.

After all, leaks from Kaw asaki told us the bike had done 197 mph in testing, and corpo rate chest-pounding from a company representative includ ed, "This bike is so beyond anybody. It's amazing," and, "We didn't build it to be slower than the Suzuki."

Except that it is. Welcome to the bizarre world of the ZX12R, where political pressure has collided head-on with corporate ego, and Kawasaki’s attempt to retake the speed-king throne coincides with a movement hatched in Europe to limit the top-speed of production motorcycles to 186 mph (see “Speed Bleed,” page 41).

The bottom line, according to Kawasaki USA, is that the biggest Ninja has been slightly neutered, its engine-control unit altered (and possibly, said our source, final gearing) to reduce the bike’s top speed to within proposed limits, which, practically speaking, it now is. This led us to wonder about the 2000 Hayabusa. If Kawasaki tamed its tour de force, did Suzuki do the same to the GSX1300R? Apparently not yet (at least on U.S. models), as the Y2K Suzuki managed 191 mph, just 3 mph slower than our 1999 ’Busa’s best.

Then, to add another dimension to this wacky story, less than two weeks after giving us the bike, Kawasaki took it away, standing by at our last photo shoot and loading it in their truck when we finished. Evidently, a test rider from Germany’s Motorrad magazine was doing a high-speed run on the autobahn when a connecting rod let go and hucked itself through the engine case. Kawasaki Japan demanded all 12R testbikes be returned to distributors for a safety check.

Where does all this leave us? For now, the ZX-12R is what it is, which is the second-fastest production motorcycle ever made.

What’s left, then? Well, a hell of a lot-a semi-limp 12R is slower, but it is in no way slow. What we’re dealing with here is sort of a Super-Supersport. In the same way the Hayabusa upped the chassis ante as compared to the CBR1100XX, so the more agile ZX-12 does to the ’Busa.

This is a pure sportbike here, no question, but with similar otherworldly superthrust when you hit the afterburners. But where the Hayabusa feels like a sumo wrestler that also happens to be able to sprint at a world-record pace, the 12R feels like the inverse-a world-class sprinter whose favorite hobby is sumo wrestling. On a racetrack, the Hayabusa wouldn’t stand a chance against the Kawi.

Still, the Ninja’s 513-pound dry weight does lend, shall we say, a certain gravity to riding the bike aggressively. But it evidently takes a certain amount of metal to keep a 157-bhp streetbike from bending itself silly when you whack open the throttle. The bike does, however, mask its weight incredibly well, with a very masscentralized, densely packed character. The most obvious reason for its light feel is its chassis geometry; it has the most aggressive steering figures and shortest wheelbase in its class (nearly 2 inches shorter than the ’Busa and XX). So when it comes time to hustle all that horsepower and heft through tight switchbacks, you don’t get off the bike sweating and overexerted. In fact, you’re surprised and delighted at how well it works and how easy it is to steer. And

high-speed sweepers? Hard to find a better bike for those.

Essentially, this is because the bike was designed as the ne plus ultra Ninja, a machine that takes ZX sportbike characteristics into the 1200cc class. And so, the 23.5-degree rake and 3.7 inches of trail mimic those of the smaller Ninjas. The 56.8-inch wheelbase is slightly longer than the sportbike norm, but the normal sportbike doesn’t have to remain stable at speeds so enticingly close to 190 mph. The ZX-12 does, and it feels only slightly less planted at the Warp Factor end of the spectrum than the remarkably rock-steady Hayabusa.

But while the frame specs aren’t at all out of the ordinary for a modern sportbike, the frame itself is. It was one thing to hear about the aluminum monocoque that runs over the top of the engine and forms part of the airbox, but quite another to take the bike apart and have a look for ourselves.

With the frame/airbox occupying much of the space normally reserved for fuel, the actual tank (the green “tank” you see is a screw-on plastic cover) resides mainly under the rider’s seat. The whole affair is hinged to allow access to the pair of flat air filters that slide side-by-side into slots in the black aluminum. There are cast-aluminum, bolt-on covers located behind the filters that allow access inside the airbox and to the intake throats. Unusual and interesting to look at. From the side, instead of fat frame spars, you get a direct view of the nearly vertical intake tracts and 46mm fuel-injection throttle bodies. The compact cylinder head and magnesium engine sidecovers (some beveled for cornering clearance) are in plain view. The sheer size of the clutch cover suggests what’s underneath is ready for the abuse that comes from having 90 foot-pounds of torque on tap. It held up very well considering our multiple dragstrip flogs and general testbike thrashing. (“Fook at me! I can go from 0-60 in 2.7 seconds!”)

Overall, what this unusual chassis does for the 12 is make it remarkably narrow for a big-bore Four. And although this narrowness helps keep the bike from feeling cumbersome, what Kawasaki was looking for in the frame design (aside from holding the bike together) was a reduction in frontal area, to aid aerodynamics and so top speed. The whole of the bike’s styling apparently owes itself to the pursuit of speed: the winglets on the fairing (to help separate smooth, upper-fairing airflow from the lower, turbulent air whipped up by the front wheel); the small radiator opening; the raked windscreen; the weirdly shaped, ’68 Camaro-style mirrors (which buzz and fuzz the rearview); the smooth fairing sides; and full-length belly pan. All do their part to ease the bike’s passage through the atmosphere.

A shame, then, that at 187 mph, there was 700 rpm left before redline in sixth gear, the engine apparently unable to exploit the benefits of the much touted aerodynamics... Exactly how the power output of the engine was reduced we don’t know. Was bhp attenuated over the whole rev range, or just on top? Or only in sixth gear? Is it simply overgeared? Kawasaki is not saying. Whatever the case, acceleration is nonetheless fierce. Roll-on times were, in practical terms, equal to those turned in by the 2000 Hayabusa tested the same day, which puts them among the best we’ve ever recorded.

The ll98cc, four-valve-per-cylinder inline-Four, while not based on the ZX-9R or 6R, features the same rev-happy boreto-stroke ratio and general layout. Power character reflects this, as does the 11,500-rpm redline (electronic cutout occurs at 12,200). For while there is ample bottom-end torque, it doesn’t feel that earth-shattering (could this be Accelerative Brain Disorder, a permanent realignment of our cells brought about by our long-term Hayabusa?). But from 7000 rpm on up, it’s as if God’s own hand descends from the heavens to lend a shove. Roll on the throttle in the upper reaches of the rev range and the world before you explodes. Comer exits rule.

The entrances aren’t too bad, either. Suspension is typical Kawasaki sportbike-response hovers precariously close to harsh, without quite crossing the line. Putt around town or cmise the freeway, and you’ll be constantly reminded that you are on a real sportbike. Of course, this is damping that is also supposed to keep a motorcycle stable at extremely high speeds, so we’ll take slightly stiff over a 150-mph tank-slapper any day!

So, yeah, it knocks you about a bit as you crawl through traffic to work, but tear it up on your favorite backroad and you are greeted with low-effort steering, ample ground clearance and good feedback from the front end. Stability is never in question, just relax and enjoy your ride. Braking performance, too, is excellent, both empirically (60-0 was a super-short 118 feet)

and subjectively (good feel, not grabby initially and easy to modulate at the limit). About the only thing that will confound you is the choppy response from the fuel injection. Throttle response at small openings, and from off the gas to on to settle the bike in a comer, is rough-defmitely needs some refinement here. It’s no worse than the Hayabusa, but now that we’ve seen the glory that the Aprilia RSV Mille’s and Honda CBR929RR’s fuel-injection systems offer, nothing less than perfect will do.

Aside from the taut ride and dodgy throttle response, everyday use proves quite pleasant. The riding position is “sporting-comfortable,” the fairing offers good wind protection and there are no obtmsive vibes from the counterbalanced engine, just a sort of “grainy” feeling at certain rpm. It’s smoother than the Hayabusa, but nowhere near the super-smooth, ultra-refined Double X, still the Velvet Sledgehammer of the class. The ZX-12 feels more raw, more brutal. In the Olden Days, we would have called it a Man’s Bike. But we wouldn’t do that now.

While discussing where the ZX-12 fits in with the other corporate ego flagships, one pundit offered that the Kawasaki is the best sportbike of the bunch, a more than deserving heir to the ZX-1 l’s throne. Then, someone asked, “But is it a good sportbike? Or is the concept of this kind of motorcycle fundamentally flawed?” It’s a relevant question. In pure sportbike terms, there are better all-around motorcycles that are lighter in weight and easier/less intimidating to ride. They may have less outright acceleration and not even approach the still-impressive 187-mph top end of the ZX-12, but are perhaps more suited to the constraints of actual road riding.

But that’s not the point of this kind of motorcycle. This is a different kind of drug. You have to want what a ZX-12 represents as much as what it actually is. Extra weight, or chassis specs that promote stability at supra-legal “buck-a-hundred” top speeds are the price of admission for riding a hairy green brute like this. Unfortunately, what Kawasaki was trying to achieve in the ZX-12R has apparently been blunted. It is, however, an incredibly capable big-bore supersport bike. In fact, it is the most capable—a very big stick. It’s true we may never know what it was capable of in its uncensored form, and that’s a shame. But if you let 7 mph and .18 of a second come between you and this incredible sportbike, that would be an ever bigger shame. □

KAWASAKI ZX-12R

$11,999

Kawasaki Motor Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Great Clinton Land Grab

June 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOuter Daytona

June 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWays And Means

June 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupV-Twin Attack! Ktm Targets Japan Inc.

June 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRoost In Peace, Joe Motocross

June 2000 By Wendy F. Black