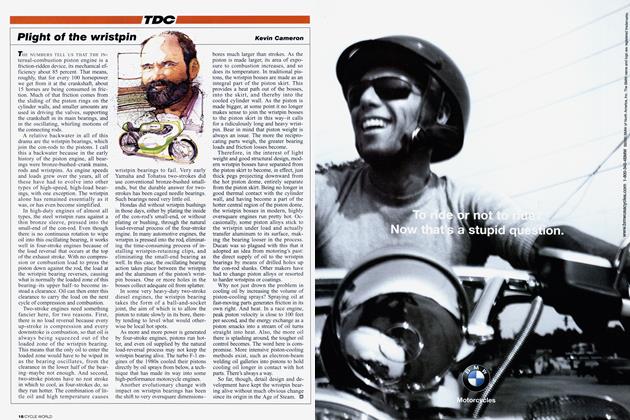

MOtO Parilla

FORZA ITALIA

Not Fade Away

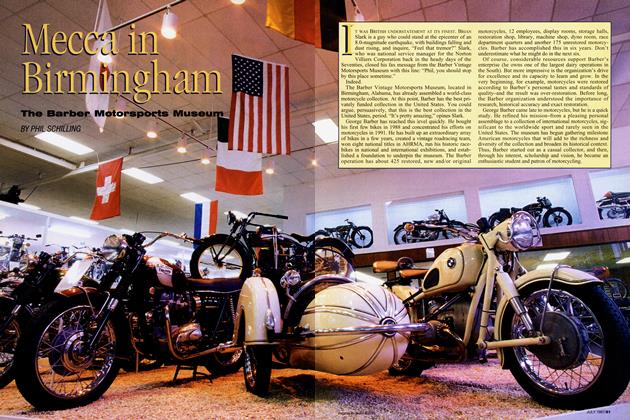

PHIL SCHILLING

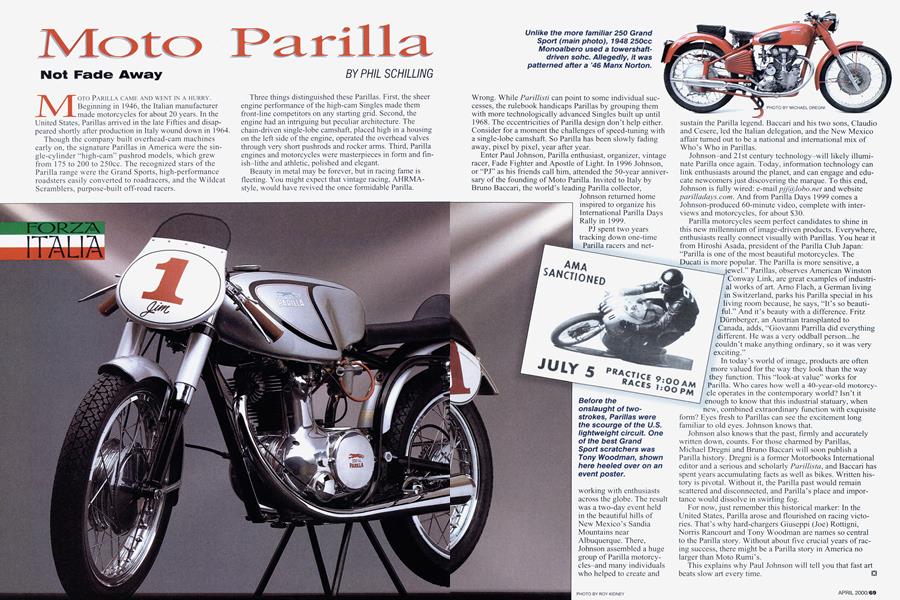

MOTO PARILLA CAME AND WENT IN A HURRY. Beginning in 1946, the Italian manufacturer made motorcycles for about 20 years. In the United States, Parillas arrived in the late Fifties and disappeared shortly after production in Italy wound down in 1964. Though the company built overhead-cam machines early on, the signature Parillas in America were the single-cylinder “high-cam” pushrod models, which grew from 175 to 200 to 250cc. The recognized stars of the Parilla range were the Grand Sports, high-performance roadsters easily converted to roadracers, and the Wildcat Scramblers, purpose-built off-road racers.

Three things distinguished these Parillas. First, the sheer engine performance of the high-cam Singles made them front-line competitors on any starting grid. Second, the engine had an intriguing but peculiar architecture. The chain-driven single-lobe camshaft, placed high in a housing on the left side of the engine, operated the overhead valves through very short pushrods and rocker arms. Third, Parilla engines and motorcycles were masterpieces in form and finish-lithe and athletic, polished and elegant.

Beauty in metal may be forever, but in racing fame is fleeting. You might expect that vintage racing, AHRMAstyle, would have revived the once formidable Parilla. Wrong. While Parillisti can point to some individual successes, the rulebook handicaps Parillas by grouping them with more technologically advanced Singles built up until 1968. The eccentricities of Parilia design don’t help either. Consider for a moment the challenges of speed-tuning with a single-lobe camshaft. So Parilia has been slowly fading away, pixel by pixel, year after year.

Enter Paul Johnson, Parilia enthusiast, organizer, vintage racer, Fade Fighter and Apostle of Light. In 1996 Johnson, or “PJ” as his friends call him, attended the 50-year anniversary of the founding of Moto Parilia. Invited to Italy by Bruno Baccari, the world’s leading Parilia collector,

Johnson returned home inspired to organize his International Parilia Days Rally in 1999.

PJ spent two years tracking down one-time Parilia racers and networking with enthusiasts across the globe. The result was a two-day event held in the beautiful hills of New Mexico’s Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque. There, Johnson assembled a huge group of Parilia motorcycles-and many individuals who helped to create and sustain the Parilia legend. Baccari and his two sons, Claudio and Cesere, led the Italian delegation, and the New Mexico affair turned out to be a national and international mix of Who’s Who in Parillas.

Johnson-and 21st century technology-will likely illuminate Parilia once again. Today, information technology can link enthusiasts around the planet, and can engage and educate newcomers just discovering the marque. To this end, Johnson is fully wired: e-mail pjj@lobo.net and website parilladays.com. And from Parilia Days 1999 comes a Johnson-produced 60-minute video, complete with interviews and motorcycles, for about $30.

Parilia motorcycles seem perfect candidates to shine in this new millennium of image-driven products. Everywhere, enthusiasts really connect visually with Parillas. You hear it from Hiroshi Asada, president of the Parilia Club Japan: “Parilia is one of the most beautiful motorcycles. The Ducati is more popular. The Parilia is more sensitive, a

ewel.” Parillas, observes American Winston Conway Link, are great examples of industrial works of art. Amo Flach, a German living in Switzerland, parks his Parilia special in his living room because, he says, “It’s so beautiful.” And it’s beauty with a difference. Fritz Dümberger, an Austrian transplanted to Canada, adds, “Giovanni Parrilla did everything different. He was a very oddball person...he couldn’t make anything ordinary, so it was very exciting.”

In today’s world of image, products are often more valued for the way they look than the way they function. This “look-at value” works for Parilia. Who cares how well a 40-year-old motorcycle operates in the contemporary world? Isn’t it enough to know that this industrial statuary, when new, combined extraordinary function with exquisite

form? Eyes fresh to Parillas can see the excitement long familiar to old eyes. Johnson knows that.

Johnson also knows that the past, firmly and accurately written down, counts. For those charmed by Parillas,

Michael Dregni and Bruno Baccari will soon publish a Parilia history. Dregni is a former Motorbooks International editor and a serious and scholarly Parillista, and Baccari has spent years accumulating facts as well as bikes. Written history is pivotal. Without it, the Parilia past would remain scattered and disconnected, and Parilla’s place and importance would dissolve in swirling fog.

For now, just remember this historical marker: In the United States, Parilia arose and flourished on racing victories. That’s why hard-chargers Giuseppi (Joe) Rottigni, Norris Rancourt and Tony Woodman are names so central to the Parilia story. Without about five crucial years of racing success, there might be a Parilia story in America no larger than Moto Rumi’s.

This explains why Paul Johnson will tell you that fast art beats slow art every time. E3