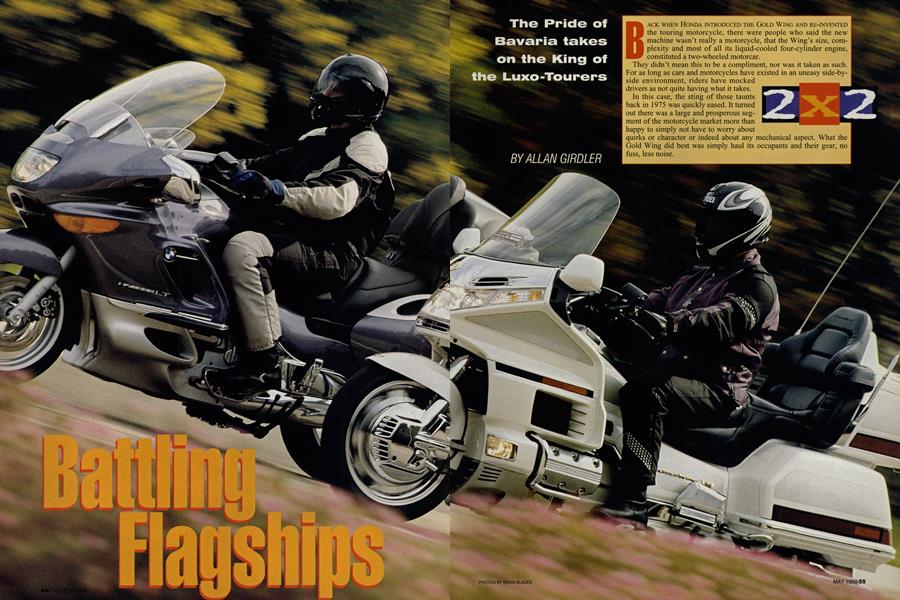

Batting Flagships

The Pride of Bavaria takes on the King of the Luxo-Tourers

ALLAN GIRDLER

BACK WHEN HONDA INTRODUCED THE GOLD WING AND RE-INVENTED the touring motorcycle, there were people who said the new machine wasn't really a motorcycle, that the Wing's size, complexity and most of all its liquid-cooled four-cylinder engine, constituted a two-wheeled motorcar.

They didn't mean this to be a compliment, nor was it taken as such. For as long as cars and motorcycles have existed in an uneasy side-by side environment, riders have mocked _____________ lldrivers as not quite having what it takes.

In this case,' the sting ofthose taunts back in 1975 was quickly eased. It turned out there was a large and prosperous seg ment of the motorcycle market more than happy to simply not have to wony about quirks or character or indeed about any mechanical aspect. What the Gold Wing did best was simply haul its occupants and their gear, no fuss, less noise.

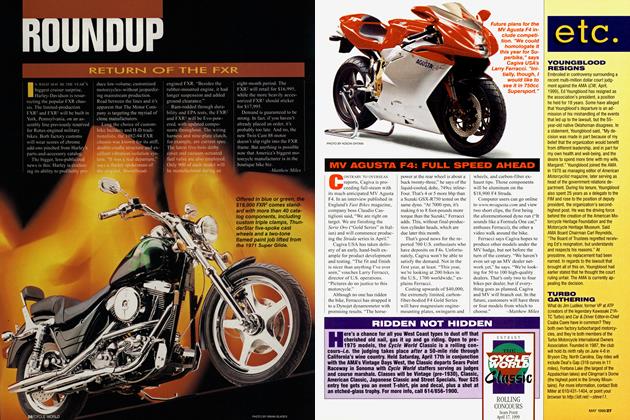

BMW K1200LT vs. Honda GoldWing SE

The Gold Wing has gone from strength to strength, and from four to six cylinders plus extras like reverse gear. In the Wing's wake have followed rivals from the usual sources, the other major manufac turers who have done their versions of the theme.

Comes now BMW and the new-for-1999 K1200LT.

BMW’s previous touring models have been more in the bolt-on mode, as in the K1100LT with Vetter-look fairing, bags and box. It’s done well enough, but it wasn’t the Wing’s equal in terms of creature comfort or sheer list of features.

BMW therefore determined the way to match Honda and get some of that topline touring market share was to do what Honda does. Draw up a complete package, every component designed to work with every other component, nothing added or needed later.

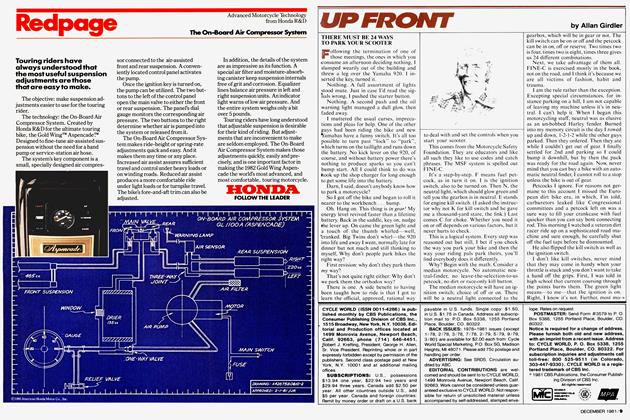

BMW began with the basics-engine, gearbox, main frame, Telelever front suspension and one-sided Paralever swingarm from the K1200RS sport-tourer. The engine’s power curve was reshaped, with the peak lowered and the fat part made fatter, thanks to shorter camshaft timing and smaller intake ports. The swingarm was extended 3 inches, to allow room for the anticipated luggage and for highspeed stability, and the rear subframe was beefed-up for extra loads.

The major extra, though, is reverse gear. This is actually a rework of the starter motor, in that there’s a switch to reverse the direction of rotation and then the rider thumbs the start button to engage the motor and move-slowly, thank goodness-backward out of the garage or up from the sloped parking spot or whatever.

Both brands have three levels-good, better and best, as Sears-Roebuck used to say. Our Beemer was the top-o’-theline Custom model, with all the radio goodies, heated handgrips and (yes!) heated seat/backrest. Our test Wing was the SE, also the top-shelf model.

Hidden by the BMW’s all-enclosing bodywork are what used to be known as crash bars, those big hoops the old Harleys used to have fore and aft, so when the bike fell over it wouldn’t on the carburetor or the rider’s legs. BMW added outriggers, sort of, fore and aft, positioned so they’re part of the paneling and thus not noticed, but they are Hell for stout and they are covered with the sort of material used for car bumpers. And they serve the same purpose. These are big motorcycles, 800-plus pounds, and while the designers have done much to keep the centers narrow and to provide ease of foot-ground access, tipovers happen.

In fact, the press launch ride, in the Texas Hill Country of Willie Nelson fame, was less than an hour old when one of the riders stopped on a slope, put out a foot...and tipped over. It wasn’t our man, we’re quick to say, but our chap did help right the bike, and in fact there was literally not a scratch on the paint or chrome, not a nick anyplace.

Anyway, what we’ve got here are two turnkey tourers in the best sense of the phrase-turn the key, push the button, go. GL and LT buyers head for the horizon secure in the knowledge that both bikes will climb any grade, average any speed that won’t result in jail, slog through any degree of heat or cold on the planet, and never once hiccup or stumble or display any temperament at all.

Okay, we can pause here and reflect that part of the fun of motorcycling has been...well, the unknown, the fact that roadside repair might be needed, while the campfire glowed just a bit brighter when you’d outrun the storm that would have drenched you if you’d been caught.

All true, and to some degree like kickstarting, which holds more charm some days for those who used to do it than for those whose engines still need it.

As in? As in when it’s dawn in New Mexico, in the winter and just this side of the Continental Divide, and you walk out of the motel room, click on the BMW’s instrument panel and the ambient temperature blinks on at 35°F, it’s impossible not to be very glad for the full fairing, the heated grips and seat, and the outlets for the electric vest and chaps, never mind that these engines will fire up in two spins, no skill required, and won’t need to be even thought about for the rest of the day.

Which is not to say science doesn’t have limits.

For instance, the Honda’s windshield can be adjusted with some fiddling, while the BMW’s shield zips up and down via a switch and electrical power. Still, the laws of aerodynamics cannot be fooled. What we get here, on both machines, is a pair of great big fairings, the BMW’s especially. If streamlined and barn door can be combined into a phrase, this is where that phrase applies. But neither fairing provides a completely draft-free environment. Some settings are better than others, some curl more or less air onto the rider’s kidneys and/or back of the neck, but none of our riders could find a setting that put them in perfect still air at speed.

So nothing is perfect.

That’s worth noting here because this isn’t the usual comparison test. If the subject was 250cc motocrossers, lap times would be the deciding factor, likewise for 600cc Fours, and so on. Most of the time, for most motorcycles, there are practical matters like top speed or cornering clearance to decide the matter.

But not here. The Wing and the LT both will deliver more than the touring rider-we assume here the Daytona 200 and Paris-Dakar are not on the agenda-can use.

What we come up with is an odd sort of objectivity.

For starters, the subjects were in company on a Sunday in central Arizona when the crew hap pened upon a touring club, all makes welcome, all machines big, having lunch. Instant focus group, as they say in the marketing busi ness, and a quick and accurate way to poil the public.

The Honda was welcome and respected. It is, afterall, a known quantity.

The BMW was anticipated, as in these people read the magazines, they knew the K1200LT was on the way, and they poked and pried and commented. They were impressed, while at the same time there was no wholesale rejection of the parked Harleys, Yamahas, Hondas and BMWs in the group.

But-and any industry types reading this are welcome to take notes-what occasioned most of the comment reflects more on the state of touring-bike ownership than on the new models: What the touring riders like best and most was the LT’s single-sided swingarm. The BMW has a centerstand, so the owner can lift the bike, use the toolkit to remove the rear wheel and schlepp it into the trunk of his M3 or 2002 and get the new tire fitted quick and cheap.

The Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki competition entails an hour or so of flat-rate labor just to get the rear wheel off, never mind that the Harley doesn’t even have a centerstand.

Just because you can spend $20,000 on your motorcycle doesn’t mean you like leaving the bike at the dealership and spending $50 just to remove the rear wheel, and our focus group wants to know why the other makes haven’t followed BMW’s lead. Is there a patent involved? (No, by the way, the rivals haven’t got the word yet, is all.)

As it happened, the question of Which Wins? can be answered, fairly and briskly, on the basis of two major factors in the touring equation.

One of these factors is...well, subjective, and the other goes to the heart of what these machines are about.

The first factor, the one that’s not quite logical, involves fuel mileage and range. First off, the BMW is more efficient. That’s logical, in that a 1200cc Four is more likely to have lower pumping losses than a 1500cc Six, pushing the same size fairing at the same high cruising speeds. So it follows that when the Honda was in the low 40 mpg’s, the BMW was in the highto mid-40s, and when the bikes were really working, the Honda dipped into the 30s, while the BMW didn’t.

But that’s not the full story.

There’s a bit of folk wisdom about how when you have a watch, you always know what time it is, while when you have two watches, you’re never quite sure.

The BMW has a fuel gauge and a fuel-warning light and a built-in computer that tells you what the mpg has been since the last fill-up and how many miles you can go before you run out. That’s three watches to tell you the time*.

What that means is, the rider gets to watch for the light and wonder why it came on sooner this leg, in terms of where the needle is on the gauge, than it did the earlier leg, and then key in the mpg to see how that compares, and then the miles-to-go function says heck, you got 120 miles, leading to the question, why did the light come on?

This is fun. Foolish, but fun, and it gives the BMW pilot something to do when the interstate yawns ahead and the radio will only get bad C&W and the next disc in the stack is ZZ Top and the rider feels more like hearing Yo Yo Ma...oh, it’s rough, life on the road.

BMW

K1200LT

$18,900

Against that, the Honda's light comes on early and there is no way to second guess. Worse, the warning arrives not too deeply, make that not deeply enough, into the second hundred miles of a given leg. The Gold Wing lacks range. The SE rider finds himself looking to fill-up every 150 miles or so. There you are in West Texas, between Junction and Sonora, and if you don’t stop now, you’ll be forced to stop at one of two two-pump towns where they’ve added 30 cents per gallon ’cause it’s them or a long walk.

Honda

GL1500

$17,999

Touring is supposed to be the open road, the purple mountains’ majesty, the frolicking deer and antelope. It’s not supposed to be, Oh geez, 30 miles to the next service, lessee now...

The BMW, which rolls up 200 miles-plus between tankings, and lets you know how closely you can shave it, wins this portion.

More useful in the long run is that each of these bikes has what we could call a span of competence.

Climb aboard the Gold Wing and the newcomer feels instantly at home. The engine fires freely and revs like a sportbike, wing! wing!, sounding like a tuned Porsche-an opposed-Six is an opposed-Six, after all. The controls are light and the steering seems quick and sure. The parking lot holds no terrors.

The BMW’s first impression is isolation. The engine sounds remote and the rider feels removed, somehow, from the machine, like in a car if one can make that comparison one final time. The bars, meanwhile, are like the tillers one sees on those 1912 museum pieces. Once underway, concentration is required, as the steering at parking-lot speeds has some waver. Intimidation is the initial impression from the LT. The first-timer finds himself taking notes: Be ready for corrective action.

Things get equal when the parking lot gives way to city streets and country highways. The controls are balanced and sure, and as mentioned there’s so much more performance available than can be used, neither machine is working hard and the riders can sit back and dial-in the sound systems.

This is where both are equally at home and at ease. Every amenity is on offer-okay, one rider quipped he began searching for the TV’s remote control-but aside from that, every extra a motorcycle tourist can use is there. Enjoy the ride.

Just as the Honda’s competence begins at lower speeds than the BMW’s, so does the BMW work where the Honda begins to struggle. The LT has better suspension. The design is newer and offers more control, as in lack of dive under braking. The Beemer is better damped and glides over the bumps and ruts to which the Honda can only react.

These are not sportbikes. Even so, there may be times and places when riders wish to make some time, or may need to take action. Under such circumstances, both machines will ground out. The BMW touches down, as in the pegs hit the pavement and ripple along, letting the rider know he’s used up all the (generous) clearance. At lower speeds and less lean angle, the Honda hits bottom, with solid pieces banging the pavement. This is more than a warning, as the impression is one of a chassis about to lever a tire off the ground.

At higher speeds, the BMW’s superior suspension, and the settings that presumably made the steering slow in the parking lot, keep the LT comfy. No incriminating numbers here, simply let it be known that no matter how fast you go, the BMW is happy to keep you there, out of trouble.

Against that, the settings that make the Gold Wing relaxing at low speeds, make, umm, Continental rates of travel not as comfy. No flaws, surely no instability here, more like the Honda needs your full attention when the BMW has you in its capable hands.

So?

So, these are the flagships, motorcycles for the open road and the long haul. And because the BMW hauls longer and harder, the BMW wins. K3