FAME

The crux of the Vee

PHIL SCHILLING

IF YOU WANT TO BE remembered, be different. Be both different and handsome, and you have a chance for fame. Be handsome, different and effective, and your fame could rise to legend. It happened to Moto Guzzi’s V7 Sport.

Its origins made the V7 Sport a long-shot for sporting fame. Moto Guzzi created its basic V700 engine in the mid-Sixties; this utilitarian shaft-drive V-Twin mounted crosswise in a dowdy two-wheeler intended for police and military use. The V700 was long, rugged, heavy, simple and exceedingly homely. In the late-Sixties,

Moto Guzzi began making civilian versions, which arrived here as the 750 Ambassador. Its name was the most stylish thing about this ponderous lump.

That a sporting motorcycle could be fashioned from such stuff seemed fanciful, and then very far-fetched when Giulio Carcano was purged from the Moto Guzzi factory. Carcano had engineered many of the great Moto Guzzi Grand Prix bikes of the Forties and Fifties, and he also designed the V700. But one of those classic Italian business upheavals involving money, mismanagement and egos put Carcano out in 1966.

Moto Guzzi’s new chief engineer, Lino Tonti, had an extensive background in racebike design, and he soon built some highly modified Ambassadors, which in 1969 established a series of international speed records for time and distance. These successes encouraged Tonti to lobby for a high-performance 750cc sportbike suitable for production racing. Given Moto Guzzi’s shaky finances, his starting point became the touring engine.

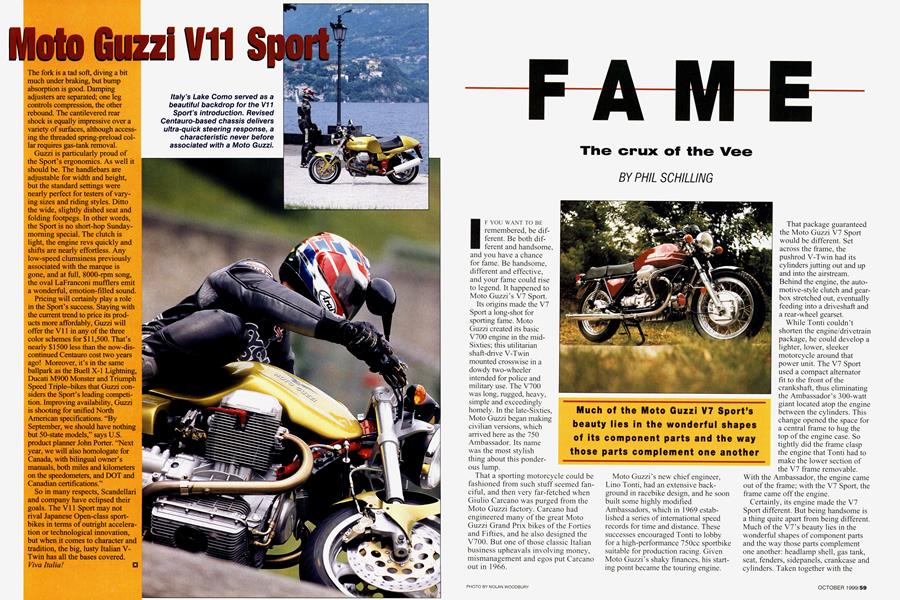

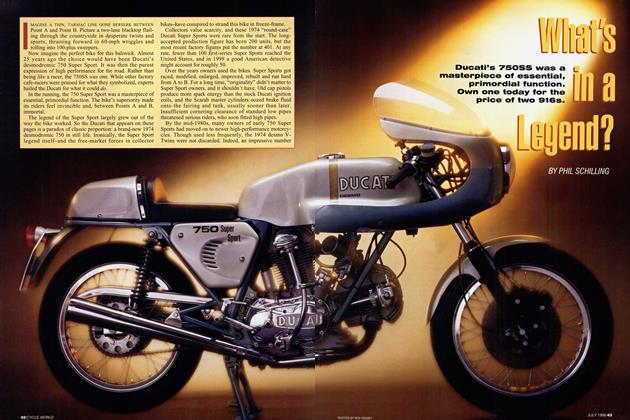

That package guaranteed the Moto Guzzi V7 Sport would be different. Set across the frame, the pushrod V-Twin had its cylinders jutting out and up and into the airstream. Behind the engine, the automotive-style clutch and gearbox stretched out, eventually feeding into a driveshaft and a rear-wheel gearset.

While Tonti couldn’t shorten the engine/drivetrain package, he could develop a lighter, lower, sleeker motorcycle around that power unit. The V7 Sport used a compact alternator fit to the front of the crankshaft, thus eliminating the Ambassador’s 300-watt giant located atop the engine between the cylinders. This change opened the space for a central frame to hug the top of the engine case. So tightly did the frame clasp the engine that Tonti had to make the lower section of the V7 frame removable. With the Ambassador, the engine came out of the frame; with the V7 Sport, the frame came off the engine.

Certainly, its engine made the V7 Sport different. But being handsome is a thing quite apart from being different. Much of the V7’s beauty lies in the wonderful shapes of component parts and the way those parts complement one another: headlamp shell, gas tank, seat, fenders, sidepanels, crankcase and cylinders. Taken together with the architecture of the running gear, the sum of the parts amounts to a very striking whole.

Simple summing can’t totally explain the visual appeal of the V7 Sport. It is a matter of scale and proportions. The machine projects an animal litheness because it’s low, lean and long; the bike has almost predatorlike proportions. In these dimensions and shapes the human eye finds something exciting and attractive.

Handsome is as handsome appears.

And handsome is as handsome does.

While the 1971-72 V7 Sport had track-certified credentials as a production racer, the open road, endlessly wound in sweeping comers, was the bike’s true venue. The engine, with more compression, carburetion and cam timing than the Ambassador, could lounge comfortably below four grand and then rush to 7500 rpm, aided and abetted by a light flywheel and a close-ratio fivespeed box.

A V7 Sport moves through space like a coyote. In nature, there’s almost a disconnect between the slow-moving lope of the critter’s legs and the sheer speed with which the animal covers distances. So it is with the Moto Guzzi V-Twin. Even working up to a frenzied 7500 rpm, the engine lopes by firing the cylinders off 270 degrees apart and then waiting 450 degrees before beginning the next one-two sequence. What passes for engine fuss is confined to some quaking and air-intake honking. Normally, the engine lulls into the background, receding out of the rider’s consciousness and leaving him to focus on the road game ahead.

Almost 30 years after its introduction, the V7 Sport is still an effective classic motorcycle for a long day’s journey. A threesome might set out on a Laverda Triple, a bevel-drive Ducati Twin and a Moto Guzzi Sport. The wisest rider would begin the day on the Laverda 1000, revel in its speed and acceleration, grow weary of its thrashiness and mass, suggest switching bikes after 90 minutes, and latch on to the Ducati Twin. The next two hours would be spent enjoying the Ducati’s taut handling, amazing smoothness and

boisterous exhaust. The third hour might be spent angling to get aboard the V7 Sport. At the end of the day, the veteran rider would want the Moto Guzzi and its civility: inconspicuous engine, modulated exhaust, race-bred handling, comfortable riding position, supple suspension, soft saddle and clean shaft drive. The V7 remains an effective motorcycle because it has a balance of sport and civility that works.

In the V7 Sport, there’s no doubt that Moto Guzzi tipped the balance toward civility. The 500-pound 750 Sport could run a standing quarter-mile in roughly 13.5 seconds at approximately 95 mph, or about a full cut below the hottest performers of the time. Moto Guzzi couldn’t get more straight-line performance without doing harm to the 750’s civil manners. Another item: After all Tonti’s brilliant work with the V7 chassis, the Sport had a four-shoe drum front brake at a time when disc brakes were already cutting-edge technology. Maybe someone at Moto Guzzi figured the expensive four-shoe drum brake, though less powerful, was more genteel than discs.

Yet another classic Italian business upheaval occurred at Moto Guzzi in 1973. This upthrust really involved ego, ego and money-in that order-because Alejandro De Tomaso was the central player.

So the V7 Sport, which had been created in the wake of an earlier convulsion, was now ushered out by the following one.

De Tomaso didn’t like the old Twins; he thought Moto Guzzi needed to build Japanese-style multi-cylinder streetbikes. He set the product-cheapening department loose on the VTwins. Moto Guzzi fit mediocre dual-disc front

brakes to the V7 series, but that was a matter of economy as much as performance. The snipping went on everywhere. The V7’s gearshift linkage that originally used heim-joints as connectors was revised to a bent-rod-througha-hole arrangement. Beginning in 1973, the incredible quality of the original V7 Sport began to be nibbled to death by the De Tomaso ducks. The faithful decried this cost-cutting, but by 1974 the V7 Sport needed replacement anyway.

Had it not been for Lino Tonti and other V7 boosters, Moto Guzzi would have never built the V7’s successor, the 850 Le Mans. Though still skeptical about the prospects of an updated Sport, De Tomaso nevertheless relented, and the Le Mans appeared in 1975.

Maybe De Tomaso at last understood the importance of being different, handsome and effective.