VIVA IMOLA!

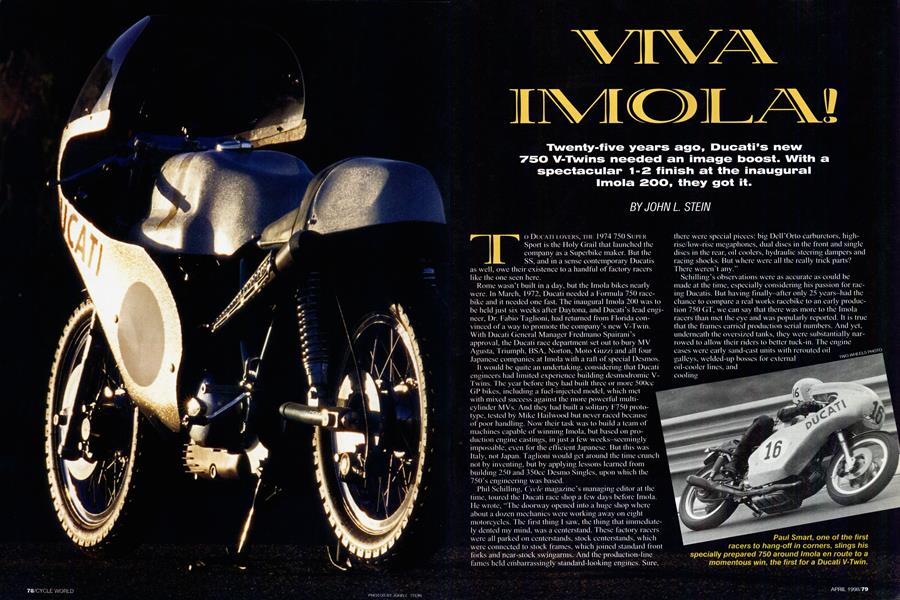

Twenty-five years ago, Ducati’s new 750 V-Twins needed an image boost. With a spectacular 1-2 finish at the inaugural Imola 200, they got it.

JOHN L. STEIN

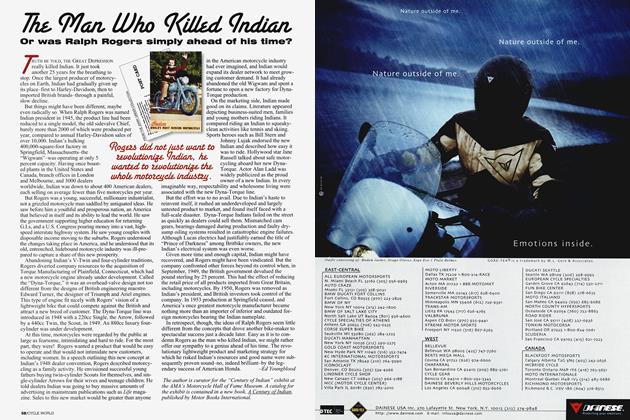

Rome wasn’t built in a day, but the Imola bikes nearly were. In March, 1972, Ducati needed a Formula 750 racebike and it needed one fast. The inaugural Imola 200 was to be held just six weeks after Daytona, and Ducati’s lead engineer, Dr. Fabio Taglioni, had returned from Florida convinced of a way to promote the company’s new V-Twin. With Ducati General Manager Fredmano Spairani’s approval, the Ducati race department set out to bury MV Agusta, Triumph, BSA, Norton, Moto Guzzi and all four Japanese companies at Imola with a raft of special Desmos.

It would be quite an undertaking, considering that Ducati engineers had limited experience building desmodromie VTwins. The year before they had built three or more 50()cc GP bikes, including a fuel-injected model, which met with mixed success against the more powerful multicylinder MVs. And they had built a solitary F750 prototype, tested by Mike Hailwood but never raced because of poor handling. Now their task was to build a team of machines capable of winning Imola, but based on production engine eastings, in just a few weeks-seemingly impossible, even for the efficient Japanese. But this was Italy, not Japan. Taglioni would get around the time crunch not by inventing, but by applying lessons learned from building 250 and 350ec Desmo Singles, upon which the 750’s engineering was based.

Phil Schilling, Cycle magazine’s managing editor at the time, toured the Ducati race shop a few days before Imola.

I le wrote, “The doorway opened into a huge shop where about a dozen mechanics were working away on eight motorcycles. The first thing 1 saw, the thing that immediately dented my mind, was a centerstand. These factory racers were all parked on eenterstands, stock centerstands, which were connected to stock frames, which joined standard front forks and near-stock swjngarms. And the production-line fames held embarrassingly standard-looking engines. Sure, there were special pieces: big Dell’Orto carburetors, highrise/low-rise megaphones, dual discs in the front and single discs in the rear, oil coolers, hydraulic steering dampers and racing shocks. But where were all the really trick parts? There weren’t any.”

Schilling’s observations were as accurate as could be made at the time, especially considering his passion for racing Dueatis. But having finally—after only 25 years—had the chance to compare a real works racebike to an early production 750 GT, we can say that there was more to the Imola racers than met the eye and was popularly reported. It is true that the frames carried production serial numbers. And yet, underneath the oversized tanks, they were substantially narrowed to allow their riders to better tuek-in. The engine eases were early sand-cast units with rerouted oil galleys, welded-up bosses for external oil-cooler lines, and cooling fins shaved to allow the right-hand exhausts to fit more snugly. The clutch baskets were copiously drilled and used straightcut gears. The ports were carefully welded up, enlarged and finely poi ished to flow gases through giant valves. The Dell'Orto PHF 40 A carbs were not produc tion units, but chokeless racing meters descended from the 500 GP program. The ignition systems had locked advances. And the coils were not Ducati's home-grown brand at all, but German units. Still, even to the trained eye the bikes looked stock, and that's exactly the impression Ducati hoped to create.

TO DUCATI LOVERS, THE 1974 750 SUPER Sport is the Holy Grail that launched the company a Superbike maker. But the SS, and in a sense contemporary Ducatis as well, Owe their existence to a handful of factory racers like the one Seen here.

While Ducati could assemble top-flight bikes on short order, it was harder to get top-flight riders. GP stars of the day who declined included Italian Renzo Pasolini, Finn Jarno Saarinen and Brit Barry Sheene. To back up the versa tile factory pilot Bruno Spaggiari, Ducati was lucky to land Paul Smart, who was fresh off a win for Kawasaki at the Ontario 200 and by all accounts at the top of his game. Now, racing an untested V-Twin from an untested big-bike maker against the likes of MV's Giacomo Agostini, BSA Triple-mounted John Cooper and Daytona winner Don Emde on a Gus Kuhn Norton would not seem to be a think ing man's bet. However, in Smart's absence, his wife had accepted the ride. He flew to Milan for testing at Modena just four days before Imola.

Daytona champ Emde's experience reflects the amaze ment most observers felt at seeing Ducati arrive at Imola

with such a show of force. He recalls, "I assumed the MV was going to be fast. I assumed the competition was going to be Agostini and whatever Triumphs and Nortons were going to be there from England. Ducati never entered my mind. The only exposure I had to Ducati was running AFM races and seeing people run little 350 Singles. We were set up in the pits and I remember that big van coming in with the glass sides. It seemed to me there were a lot of motorcy cles in the van. People were in awe of it."

The race itself has been capably told and re-told in various Ducati histories. In sum, Agostini's works MV broke, Smart and Spaggiari motored around to finish 1-2, and Ducati had well and truly engineered the paradigm shift it needed for its new V-Twin. On the silver anniversary of his victory, Smart said, "The whole thing was wonderful. They (Ducati) were so convinced they were going to win. There wasn't even the slightest apprehension; it was just a matter of going out and doing it. The bike just loped along. It didn't feel quick at all compared to the Triumph and Kawasaki Triples."

Ironically, Ducati did not seem to place much value in such history-creating it though they were. Bruno de Prato, a public ity officer for Ducati at the time, says the factory did not keep records or serial numbers of the bikes, although we now know what some of those numbers were. Also, the racing depart ment was perpetually underfunded except for a bnefpenod with big-spending Spairani. So it wasn't long before the Imola bikes were sold, shipped overseas or raided for parts for other projects. The factory saved not one of the originals. What we do know about the bikes has been garnered from two years of diligent ferreting into the minds and records of Smart, factory mechanics Franco Fame and Giuliano Pedretti (through de Prato), Schilling and Taglioni himself. Without crucial build records, the precise number of `72 Imola bikes built remains something of a mystery. Schilling counted eight at the factory workshop. An Imola photo shows seven lined up in the glass-sided transporter. And yet Smart indicates there may have been as many as 10 or 11.

In any event, we have accounted for perhaps five 1972 Imola 750s. Smart received his Imola motorcycle as a bonus for win ning the race; it lives on the wall of his Paddock Wood, Kent, Kawasaki dealership. A second bike, reportedly Spaggiari's, went to Australia soon after the race in 1972 and now resides in London. Of four bikes sent to Mosport for a summer, 1972, F750 race, one or two reportedly remain in Canada.

And then there is this bike, shipped to South Africa in early 1973 for Errol James to ride in the international South African TT and a series of nationals. In the TT, James led all comers, including the formidable Agostini, Cooper and Mick Grant, before dropping back with binding front brakes to finish fifth. James and the Imola Ducati went on to win a couple of the nationals and finished second in the 12-race South African F750 Championship behind a works 500cc Suzuki. He recalls, "That Ducati was a fast motorcycle. It was faster than the MV in a straight line."

Fast or not, the Ducati was a long way from perfect. James says, "When we got the bike it looked like it had done a long race because the tires were quite worn. They sent over a pair of new race tires with it. We used those and then put on Dunlop TT100s because we couldn't get race tires.

"We had a lot of mechanical trouble. The fork would pat ter into the corners, but we cured that with different oil. The valve gear also gave a lot of trouble. We used to race it to 10,500 rpm, but I think the redline was 9000. Parts were a problem to get because the factory was always on strike. At one stage they sent us barrels and heads and pistons, and they were all used. We were quite upset about it. The Italians weren't too good to deal with.

"The bike had two big blow-ups. First it broke a piston, and then it seized the crankshaft at a race in Angola. We gave it back to the importer, a co-op company supplying farm equipment, after that."

While James' aggressive throttle action could be blamed for engine problems, his braking and suspension woes were certainly propagated by the factory. It appears a few pieces were exchanged before the bike was sent to South Africa. Ducati historians will note that the fender mounts have not been machined off the leading-axle fork as pic indicate

Likewise, this bike has no large-volume front master cylin der filler and carries Scarab front brake calipers, possibly on the orders of Spairani, who had a financial interest in the company and would benefit from its exposure abroad. Nevertheless, this is the way the factory delivered the bike to South Africa, and the way it was raced by James.

All along, young James raced with the confidence that this was Smart's Imola-winning bike. At least, that's what the factory had reported by Telex (although Smart confirms that he took possession of his race-winner soon after Imola). But

carefully piecing together the history of the Imola bikes shows that the factory might have been at least halfway truthful. According to Ian Falloon, author of the comprehen sive The Ducati Story, during a detailed conversation about the bikes with Taglioni in 1995, it was revealed that two machines were built with a second, lower footpeg location to accommodate Smart, who was taller than Spaggiari and the other two Imola racers, Italian Ermano Guiliano and Brit Alan Dunscombe. If that is true, then this motorcycle might well be Smart's spare. Its worn tires upon arrival in South Africa in late `72 bear testimony to its engagement in battle. That could have been Greece, where Smart rode one of the Imola bikes to win at the "Greek GP" on a bumpy makeshift track. Certainly, the race was a publicity stunt for Ducati more than anything else. Years later, Smart has little to say about it. He reflects, "It was on the Greek mainland at an airfield circuit, run by the people who did the Acropolis Rally. It was in the sticks. You could win it on a bicycle."

Subsequent to its crankshaft failure, the South African SS sat-intact, but in disrepair-in the importer's lobby before being sold to John D'Oliveira, a South African racebike col lector, in 1977. D'Oliveira stored the Ducati for nearly a decade before rebuilding the engine with a fresh crankshaft and cases from the generous cache of leftover factory spares (the cases are seen in these photographs; the irreplaceable "sump plug" originals are safely stored). Sadly, D'Oliveira passed away shortly thereafter and the Ducati-along with his other bikes-fell into the stewardship of his children. The Imola racer, minus its fairing, was sold in America in 1995. What of the virginal fairing shown in these photos? In 1975, South African tuner Helmut Schaffner bought a fairing from the importer to use on a new 900 Super Sport. He had the foresight to make a mold of the fairing and one copy in case a spare was needed. It j was. Schaffner's rider soon crashed the 900, breaking P R the original metalfiake fainng "into a million pieces." After the conclusion of the 900 project, the duplicate Imola fairing hung in Schaffner's garage for over two decades before joining the bike in the U S earlier this year, thanks to a traveling businessman who had camed it on flights from Johannesburg to Zurich to the U.S. This Ducati has not been, and will not be, restored in the traditional sense. Rather, it has been corrected as much as possible. The frame, which had long ago been painted black, was disassembled and checked for align ment by Vintage Racing Services, and then resprayed in aquamarine lacquer sourced by de Prato from Ducati restoration expert Pedretti. Literally every chassis part was hand-scrubbed and reassembled. Some 30 hours of rubbing lifted incorrect silver paint off the tank, seat and fenders to reveal the original metaiflake fiberglass gelcoat. And the same TT100 tires the bike wore in South Africa were re fitted to the Borrani rims after wheel polishing and truing.

All in all, the Imola racer looks much as it did 25 years ago. It embodies everything that was representative of-and peculiar about-Ducati in the Seventies. Brilliant engineer ing. Abhorrent detailing. And unmistakable uniqueness. Most of all, it is the crucible for the fabulous 750 Super Sport, arguably the most coveted of Ducati production bikes. For without the Imola bikes, there would have been no Imola 200 win. No Imola Replicas for sale as required by FIM rules. Perhaps no "Racer Road" articles in Cycle, and no Ducati Superbike win for NeilsonlSchilling at Daytona five years later. The original 1972 Imola racers are thus more than just touchstones for today's Ducati owners. They are cornerstones.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue