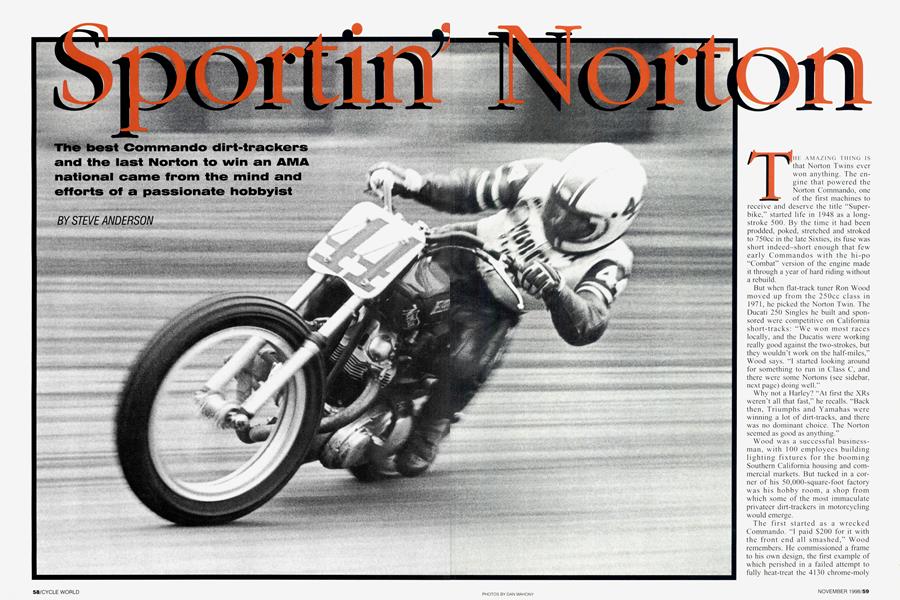

Sportin' Norton

The best Commando dirt-trackers and the last Norton to win an AMA national came from the mind and efforts of a passionate hobbyist

STEVE ANDERSON

THE AMAZING THING IS that Norton Twins ever won anything. The engine that powered the Norton Commando, one of the first machines to receive and deserve the title “Superbike,” started life in 1948 as a longstroke 500. By the time it had been prodded, poked, stretched and stroked to 750cc in the late Sixties, its fuse was short indeed-short enough that few early Commandos with the hi-po “Combat” version of the engine made it through a year of hard riding without a rebuild.

But when Hat-track tuner Ron Wood moved up from the 250cc class in 1971, he picked the Norton Twin. The Ducati 250 Singles he built and sponsored were competitive on California short-tracks: “We won most races locally, and the Ducatis were working really good against the two-strokes, but they wouldn’t work on the half-miles,” Wood says. “1 started looking around for something to run in Class C, and there were some Nortons (see sidebar, next page) doing well.”

Why not a Harley? “At first the XRs weren’t all that fast,” he recalls. “Back then, Triumphs and Yamahas were winning a lot of dirt-tracks, and there was no dominant choice. The Norton seemed as good as anything.”

Wood was a successful businessman, with 100 employees building lighting fixtures for the booming Southern California housing and commercial markets. But tucked in a corner of his 50,000-square-foot factory was his hobby room, a shop from which some of the most immaculate privateer dirt-trackers in motorcycling would emerge.

The first started as a wrecked Commando. “1 paid S200 for it with the front end all smashed,” Wood remembers. He commissioned a frame to his own design, the first example of which perished in a failed attempt to fully heat-treat the 4130 chrome-moly steel. “It ended up looking like a piece of spaghetti,” Wood says. The next one made do with more standard stress-relieving.

Wood is the type of man who could wear AMA whites while performing an engine rebuild in the pits and come away looking ready for a dinner party. This meticulousness was evident in his dirt-trackers, too, machinery whose depth of quality outshone immaculate paint and polish. Even that first Norton was full of Woodsian touches. Its integrated gas tank and seat were built from a mold he made himself, and offered a continuous surface for a rider to shift his weight-almost like motocrossers 25 years later. The steering head carried its bearings in reversible cones, so steering geometry could be varied over a 2-degree range. That first bike, Wood laughs,

was “white and powder blue-decorator colors-a designer special.”

It was ridden with some success by Eddie Mulder and others, but that first year was spent

learning how to make a Norton go fast. Power was a real issue. “When I first started working with C.R. Axtell (the legendary tuner of BSA Gold Stars who contributed mightily to the development of the Harley-Davidson XR), we were getting in the neighborhood of 60 horses,” Wood recalls. “Then we really started doing development-week after week after week...year after year. Ax was grinding his own cams back then, and he did the cam and the head work and the pipes for the bike.” The work paid off: Wood and Axtell would eventually coax 77 horses out of the long-stroke Norton engine, as measured at the rear wheel on Axtell’s famously conservative dyno.

Lessons learned on the track were the basis for Wood’s second-generation dirt-track chassis. He designed the frame as a single loop of 3-inch-diameter tubing, trying above all else to tie steering head stiffly to swingarm. The design looked simple, but the more you studied it, the more you realized that apparent simplicity was purchased with enormous manufacturing difficulty. To keep weight down, the backbone tubing chosen was only 0.049-inch thick-thinner than the cardboard used by department stores to give form to a men’s dress shirt-and far too thin to readily withstand the pounding from a solidly mounted parallel-Twin. So every engine mount was welded to a steel “pad,” spreading loads more widely. Almost all exterior oil plumbing was incorporated in the frame. The backbone tubes became the oil tank and the engine vents. Recalls Wood, “The Norton used to have so much blow-by that 1 ran the breather into the front frame tube. That connected to the top backbone tube, which exhaled through a small filter element under the seat. After every race, 1 could drain most of the engine oil from that front frame tube; the frame was really a highly designed catch bottle.”

Catch bottle or no, it worked, and Wood’s Norton carried Rob Morrison to the Ascot season championship in 1974. The Friday-night races at Ascot were a world in themselves, operating in a parallel universe to the AMA national dirt-track events. Carved into backfilled marsh, in a neighborhood of warehouses, industrial facilities and barbed wire, the Ascot half-mile was like no other. Regularly churned by sprint cars as well as by bikes, the clay surface at Ascot gathered up rubber and engine oil, sparkplugs and shattered engine bits, becoming a tacky mixture that was more industrial than natural. The track length was slightly shorter than a full half-mile, its turns banked. This was no picturesque Midwestern horsetrack borrowed for a weekend; it was a down-and-dirty motor-racing facility, one dominated by locals. The intersection between this almost-closed universe and the AMA’s Grand National Championship was always a sight to behold-the first 10 years no non-Californian won the Ascot National. And the Wood Norton came to own Ascot.

After Morrison parlayed his Ascot wins into a ride on the Norton factory team. Wood enlisted Alex “Jorgy” Jorgensen to replace him. By this time, the effort had moved out of the hobby stage to deadly serious, and the reliability issues of the Norton engine were dealt with accordingly. “The cases were so weak,” Wood comments, “that before we built an engine we had to build weld around the motor-mount bosses to keep them from breaking right off.” And indeed, when you look at the last set of Norton cases remaining in Wood’s current race shop, they look to be more weld than casting. Wood used to rotate five engines between two frames; after every race an engine was torn down and inspected. Parts were zyglowed or mag nafluxed, and re placed, on a regular basis. After all that effort, remembers Wood, "they didn't

break too much on the half-miles, but it was hard to keep them together on the miles." The key was the short dura tion of half-mile racing: Between qualifying, heat races and the final, a bike might run only 20 miles total, less than 30 minutes of hard running.

With Jorgensen on the big-tube Norton, the Ascot races were under control; the combination would win that cham pionship again in 1975 and 1976. But a national win still eluded Wood. It was a different era in dirt-track, one when factory teams still dominated, when Kenny Roberts was still riding on dirt ovals, and when Harley fielded a full four-man squad. It was tough competition for a privateer.

Wood responded to that competition with his final Norton, the bike that he would call “the lightweight.” Engine development had continued, using a short-stroke version of the Norton Twin that the factory had homologated for AMA competition. This matched the bore of the 850 Commando to a short-stroke crank for a 750cc displacement-but the efficiency of this approach was still only relative to what had come before. With an 89mm stroke and a 73mm bore, the original Norton engine had been a low-speed dinosaur, Wood turning his most hot-rodded version only to 7500 rpm. The short-stroke was still undersquare at roughly 77 x 80mm, and still didn’t have the high-speed capabilities of even an XR-750. But it was better. For this version, Wood had a one-piece crank carved from billet steel, a masterpiece of the machinist’s art with a full flywheel ring encircling the crank cheeks. “The best engine I ever built was a shortstroke,” Wood recalls. “It put out 83 horsepower.” But he couldn’t get every engine to match that one-time reading. “I could build a 78-horsepower engine most of the time-rearwheel horsepower on a real dyno.”

The chassis on the lightweight bike dispensed with the big 3-inch tubes looping fully around the engine. Instead, two small downtubes formed the front engine cradle, while a fabricated backbone held engine oil. But the most important part of the lightweight was simply its absence of weight. It scaled just 268 pounds ready to race, a good 40 pounds lighter than an XR. That was important, says Wood, “because we’d achieved what we could on horsepower, so the only improvements in the power-to-weight ratio had to come from the weight.” Wood went so far as to design the lightweight with an under-the-engine monoshock, but that met with rider resistance. “You couldn’t get anyone back then to ride anything that looked different,” Wood says. “I put twin shocks on to keep everyone happy.”

That final Norton propelled Jorgensen to the front of a number of nationals, including the San Jose Mile. He never maintained that lead through to the checkered flag, though, a source of frustration to Wood. But even competitors like Harley’s team manager Dick O’Brien noted that it was only a matter of time until Jorgy and the Norton won a national. Fittingly, it would all come together at Ascot in May, 1978. Wood shod the bike that night with a Carlisle Arrow rear tire. “No one ran them then, and no one had one on that night. Alex didn’t want to run it either, but the track surface was like mud balls,” Wood remembers. “I told Alex, ‘This has

got to work.’ And it hooked up like nothing else.”

Jorgensen won going away. It was the high point of Wood’s Norton racing effort.

There were more Friday-night Ascot wins after that, and rostrum positions in other AMA nationals. But it was the only national win that any Norton Twin would ever see on an oval track. Wood abandoned his Nortons shortly after: The factory was gone, and with it his source of standard parts. Besides, “it was like racing with no-good beer cans,” Wood says, remembering the short-fused machines as only someone who lived with their every foible for years can.

But don’t think he doesn’t have fond memories. “That

one-piece crank weighed 22.8 pounds,” Wood remembers, “and between the flywheel and the torque, when you shifted from first to second the bars would almost pull out of your hands it’d lunge so hard. No one ever beat us to Tum 1 off the start.”

Not bad for a no-good beer can that started life three decades earlier as an unassuming 500cc Twin. Ê3

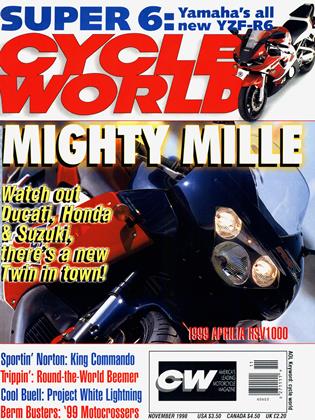

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUjm Redux?

November 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBuying A Shadow

November 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOut of Bounds

November 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley To Buy Ktm?

November 1998 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupCagiva/ducati Divorce

November 1998 By Brian Catterson