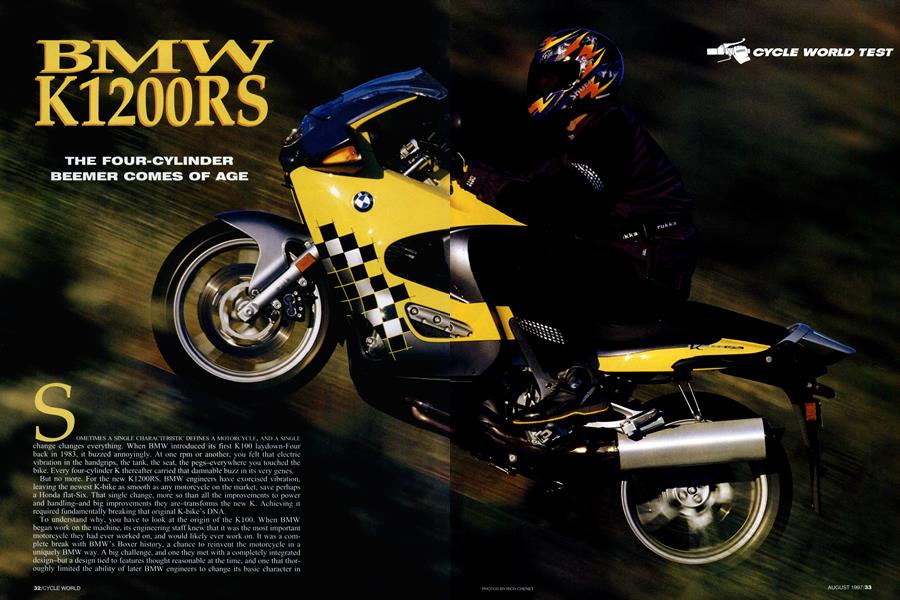

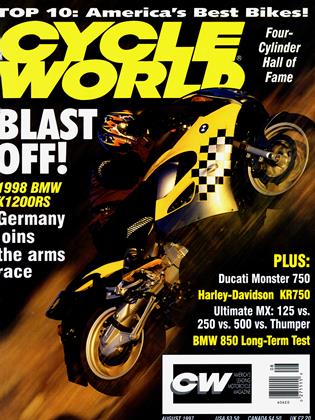

BMW K1200RS

THE FOUR-CYLINDER BEEMER COMES OF AGE

SOMETIMES A SINGLE CHARACTERISTIC DEFINES A MOTORCYCLE, AND A SINGLE change changes everything. When BMW introduced its first K100 laydown-Four back in 1983, it buzzed annoyingly. At one rpm or another, you felt that electric vibration in the handgrips, the tank, the seat, the pegs—everywhere you touched the bike. Every four-cylinder K thereafter carried that damnable buzz in its very genes.

But no more. For the new K1200RS, BMW engineers have exorcised vibration, leaving the newest K-bike as smooth as any motorcycle on the market, save perhaps a Honda flat-Six. That single change, more so than all the improvements to power and handling-and big improvements they are-transforms the new K. Achieving it required fundamentally breaking that original K-bike’s DNA.

To understand why, you have to look at the origin of the K100. When BMW began work on the machine, its engineering staff knew that it was the most important motorcycle they had ever worked on, and would likely ever work on. It was a complete break with BMW’s Boxer history, a chance to reinvent the motorcycle in a uniquely BMW way. A big challenge, and one they met with a completely integrated design-but a design tied to features thought reasonable at the time, and one that thoroughly limited the ability of later BMW engineers to change its basic character in any simple manner.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The K’s architecture was unique. Its crankshaft ran longitudinally, front-to-aft, instead of across the frame as in every other modern inline-Four, and the engine lay flat on its side. The gearbox was inline behind it. That made for a very long powertrain, so to keep the wheelbase manageable, a very short swingarm was bolted directly to the engine. The frame was reduced to little more than a simple tubular bracket that bolted to the top of the loadbearing engine. And because BMW’s management in the early Eighties had decided to unilaterally disarm themselves in the horsepower race, the K’s engine was designed for 90 crankshaft horsepower, no more, no less. Its long stroke limited high-rpm potential while its small, tightly crammed-together cylinder bores limited overbore possibilities.

In its day, the first K100 provided a more prestigious alternative to Honda’s Sabre 750, but it quickly was rendered non-competitive in performance with Japanese big-bore sportbikes. Over the years, BMW played catch-up, adding a 16-valve cylinder head, adapting a 17-inch front tire, increasing displacement to 1 lOOcc (creating the tightest bore spacing in motorcycling) and fitting its Paralever rear suspension to control shaft drive, all to keep Japanese performance at least within sight. The culmination of that piecemeal development process was the K1100RS-a big, heavy sport-tourer that still didn’t handle that well, wasn’t nearly as quick as its competition and still vibrated far too much.

It was in 1992 that BMW engineers were given the task of coming up with a comprehensive redesign of the K series, with the goal of building an RS version competitive with the Honda CBR1000F, a bike then very popular with Germanic sport riders. The only limits were financial, which meant the K-engine probably had to stay. How, then, the engineers asked, can we cure the toughest problem: vibration?

Three answers emerged. First, Lancaster-type twicespeed, counter-rotating balancers (as used on Honda’s new Super Blackbird) were examined. Though a prototype was built, packaging the two balance shafts in the existing engine configuration while providing room for the lower arm of a Telelever front suspension was simply not feasible. Scratch one solution. A second approach was to isolate the rider from the chassis by aggressively rubber-mounting bars, pegs and seat. Third was a more conventional rubber-mounting approach, the one used on most every automobile: hanging the engine from rubber. That required an abandonment of the structural and integral power-unit concept. Instead, a massive aluminum frame was to connect swingarm to front suspension mounts. Prototype testing provided the final answer: Isolating the engine was superior to isolating the rider, because by the time pegs, seat and bars were sufficiently removed from vibration, they were also removed from any direct feel of what the motorcycle was doing. The main drawback to the isolated engine was weight; the bare frame required to replace the engine structure would eventually weigh more than 60 pounds-but it worked.

With the vibration problem solved, the engineers addressed the horsepower challenge. The Kl 100RS had made 100 horsepower at the crank, enough for a current 600, but not for a heavy Open-class machine with sporty pretensions. Increasing bore size was out; the stretch to 1 lOOcc had left the aluminum cylinders of the K almost thin enough to see through. Instead, they stroked the 1100 engine by 5mm, from 70 to 75, increasing displacement to 1171 cc. Normally, a stroke increase doesn’t increase peak power, because given equivalent piston accelerations, it reduces rpm capability commensurately with the displacement bump. But in this case, the redline was maintained at 9000 rpm, allowed in part by stronger and lighter pistons and wrist pins, and the engine was thoroughly hot-rodded with higher compression, longer duration cams and valves with smaller, less flow-restricting stems. The result? The K1200 makes 30 percent more power than the Kl 100, peaking almost 1000 rpm higher! From 8250 to 8750 rpm, the K1200 pumps out 110 horsepower at the rear wheel (roughly matching BMW’s claim of 130 horses at the crank); at the 9000-rpm redline, the pistons are traveling at an average speed of more than 4400 feet per minute, more than some racing engines of a generation ago, and faster than the pistons in any other current street motorcycle engine. It’s a small wonder that the fuel injection shuts off the power almost as soon as the tach needle enters the red zone; if it didn’t, a connecting rod exiting the cases might soon do the same, but rather more permanently.

For the K1200RS, most of the changes over and beyond those required for engine isolation are aimed at making the machine sportier. The front forks of earlier Ks have been replaced by BMW’s Telelever suspension. This system, which substitutes an A-arm, fork brace and ball joint for a typical telescopic fork’s lower triple-clamp, and uses an external shock for damping, provides for the possibility of anti-dive, rather than the pro-dive geometry of a conventional fork. In its first application on the R1100 Boxer, engineers set the anti-dive ratio at 70 percent (no dive at all would be 100 percent) for largely “social” reasons-riders expect the front of a bike to dive upon brake application. But for this sportier K, the anti-dive ratio was boosted to 90 percent. To increase possible lean angle from 46 to 50 degrees, the engine was raised almost 1.2 inches. The fairing was narrowed slightly, and the riding position altered more toward a sporting crouch. Also, the clunky, mis-shifting five-speed gearbox used on both the Ks and the current R-models was replaced by a new six-speed unit manufactured by Getrag, which was given a chance to redeem itself after building the five-speed box.

But the proof is in the riding. Sit on the new K, and you can quickly tell that comfort has definitely been competing with sportiness and packaging in this redesign. The new frame, hidden plastic gas tank and gas tank cover all make for excessive width between the knees-even the front of the adjustable-height seat, as it wraps over the sidecovers, is broad. Perhaps also related to the packaging required to fit the new frame, the tank is farther aft of the triple-clamp compared to previous K’s. The bars are lower and wider, and the footpegs are positioned both farther apart and higher-even in their lowest position. It’s a much sportier riding position than on the older K-RS.

Turn the ignition key, and the fuel-injected engine starts instantly, falling into an idle right around 1000 rpm. The third-generation Motronic engine controller automatically adjusts the idle, so there’s no longer a manual “choke” control on the handlebar. And even if the K1200 has been sitting on the sidestand overnight, there’s no oil smoke from the exhaust, that old K-bike bugaboo long since cured. Pull in the now-hydraulically operated clutch, click down on the precise and shortthrow gear lever, and motor away. The K12 pulls Open-class hard, but its weight and power hold it to an 11.2-second, 122-mph quarter-mile performance, compared to the mid-10-second, 130-mph-plus numbers of big-bore Japanese bikes. But the feel is very different. The K, with more flywheel weight, is slightly slower revving than most Japanese big bores, and other than a slight dip just past 5000 rpm, has a very smooth torque curve. And the new six-speed (still slightly clunky, but seldom missing a shift) provides extremely little backlash. It all adds up to very high traction and seamless acceleration and deceleration. Unlike previous Beemers, this is a bike that’s at least tolerant of ham-fisted riders. Smoothness still counts, but throttle on/off transitions aren’t light-switch abrupt. Plus, its high torque provides good performance even if you’re not screaming toward redline.

The chassis performs as seamlessly, if not more so. The Telelever front end impresses with its compliance and overall behavior. You can look at the travel rings where the scraper has removed dust from the fork tubes, and see the bike is only using about 2 inches of its 4.8inch front travel in most riding-and that includes heavy braking. So the K1200 just does not seem to pitch much, and it always has travel in reserve while braking hard.

Which brings us to the ABS. Standard on all K1200RSs, the anti-lock works exactly as advertised, hauling the bike down smoothly in commendably short distances, with very good lever feel. The Paralever rear suspension is largely a carry-over from the K1100RS, and still has more than 100 percent anti-squat-meaning that the rear end of the bike rises mildly on acceleration. BMW development engineer Berthold Hauser admits that’s a legacy of BMW history, with the high degree of anti-squat left in on the first Paralever applications to make the bike feel more familiar to long-time BMW riders. Maybe in the future it will be reduced further, but it would have taken a new rear gearcase for the K1200RS, something neither time nor money allowed.

If you didn’t know the K1200RS had a 61-inch wheelbase, 27.3-degree rake, 4.9-inch trail and weighed 646 pounds wet, you probably wouldn’t guess those numbers. The bike steers much more lightly and precisely than the steering geometry indicates, and bends gracefully into turns. It combines exceptional stability with quick-turning capability. Sharp bumps in low-speed comers can upset the rear suspension slightly, letting the back tire step out under acceleration. For that, blame the high unsprung weight that comes with the shaft final drive. But in a sweeper, even one taken at over 100 mph, nothing can upset the big K. The suspension will absorb nasty dips and depressions that would have many other machines wobbling, and the K just tracks through unperturbed. The tight driveline and smooth-responding engine help; the K1200 is an easy machine to ride quickly.

Flaws? There are a few. The upper position of the adjustable front windscreen gives you a choice of turbulent air on your helmet or a shimmery view through distorted plastic. The riding position is perhaps a little too sporty for general American street riding. All the various adjustments give you largely a choice between adequate leg room and slightly too low bars, or a nice frontal lean with cramping knees. If you want the seat in the higher of its two positions, you have to reset it every time you take off the seat to access the tool kit or underseat storage, and that can be a fiddley, frustrating process until you learn the precise tricks. Given 20 more minutes and the on-bike tool kit, you can raise the pegs yet farther and lower the bars even more-unless your planned destination is a racetrack, the question is why would you want to? On at least two of the first-off-the-line models at BMW’s press introduction, the fan failed to cut in during slow city riding, leading to overheating; hopefully this won’t be a problem in production. Also, the hom on our testbike failed. And the $16,890 price tag (including heated grips and bag mounts, but not bags) is high; fortunately, the discount-aware can save $500 getting the bike in solid red or blue instead of the yellow with blackand-white checkers of our test machine.

But in general, the new K1200RS has been transformed into a sporty horizon-chaser, a fast machine that handles as well as anything on roads with fast comers, tolerates switchbacks, and carries you in comfort and convenience as far as you want to go.

And, best of all, that damned buzzing is gone forever.

EDITORS' NOTES

SAY WHAT YOU WILL ABOUT THE K1200RS’s girth, but this is sport-touring at its finest. Thousand-mile days? No problem. The rubber-isolated laydown-Four is incredibly smooth, even at triple-digit speeds. And the changeable ergonomics suit me-all 6-foot, 2inches of me-just fine. Kudos also to the responsive steering, stout brakes and smart-looking wheels.

Amidst all this goodness, there are a few negatives: The odd handlebar switchgear still exists (albeit in refined form), the Paralever rear suspension doesn’t follow undulating tarmac as compliantly as the Telelever front, and the longish sidestand tang has already felled one staffer. And then there’s the price.

Given the means, though, I’d go for it-minus the checkerboard graphics, please. There’s no other motorcycle that eats up open road as capably and smoothly, and with such little effort. Now, where did I put that Montana road map? -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

I DON’T LIKE THIS MOTORCYCLE, NOT ONE bit. Why? Lots of reasons, but mostly because I’m confused by its mission. It’s a sport-tourer, yet its lines and the racy checkered flags emblazoned across its sizable sides suggest it’s a sportbike.

When I first saw photos of BMW’s new 130-horsepower K-bike, I was jazzed. But when I saw it in the flesh, I was struck by the sheer size of it. It’s like someone put a photo of a Ducati Paso on a copy machine and pressed the button for a 140 percent enlargement. The K12 reminds me very much of BMW’s last attempt at a “sportbike,” the overweight, underloved Kl. Yet the new bike is 22 pounds heavier than the old one-not to mention 87 pounds heavier than Honda’s CBR1100XX, and an incredible 161 pounds more than a VTR1000 Super Hawk. Ironic, isn’t it, that in this Year of the Twins, a company known for its Boxers would build a heavyweight Four?

Oh, you say the K12 is also available without the checkered-flag motif? That’s better, but I’d still prefer an RI 100RS. -Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

HEY, I LIKE THE YELLOW K-STER! CALL IT the world’s coolest, quickest Checker Cab. Not that my good pals in the Airheads Beemer Club-luddites of long standing, dedicated to the oldstyle Boxer Twin-will be all that impressed. Besides the two extra cylinders and that new-fangled radiator device, the K1200 is equipped with no fewer than 16 dash-mounted idiot lights, not to mention an overdone right-side footpeg bracket that could double as a bridge truss. No wonder this thing is pushing 700 pounds fully fueled.

Well, at the risk of having my honorary club membership revoked, guys, I have to tell ya this is one sweet-running steamroller. Forget the added avoirdupois, the motor is the message here: fluid power, bags-o-torque and no mo’ vibramassage effect. One quick rip through the gears and I was a believer. Three cheers for the first 150-mph Bay-Emm-Vay.

So, the 1200 is definitely a better K-bike. Whether or not it’s a better Beemer, well, I’ll leave that to your own sensibilities. -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

BMW

K1200RS

List price_$16,490

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Ten Best

August 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Thousand Phone Calls

August 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPhilosophic Conversions

August 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupJapan Waxes Nostalgic

August 1997 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupUnidentified Flying Objet D'Art

August 1997