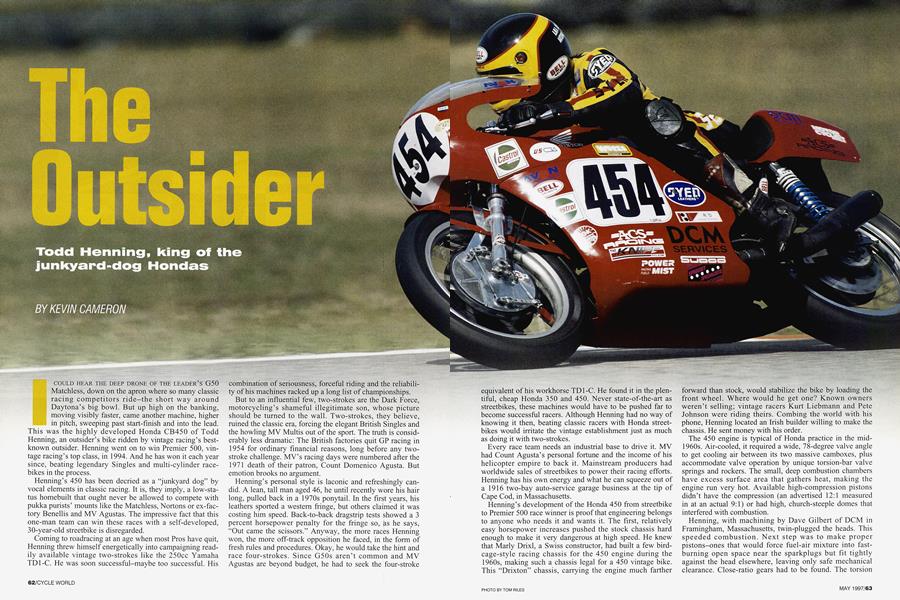

The Outsider

Todd Henning, King of the junkyard-dog Hondas

KEVIN CAMERON

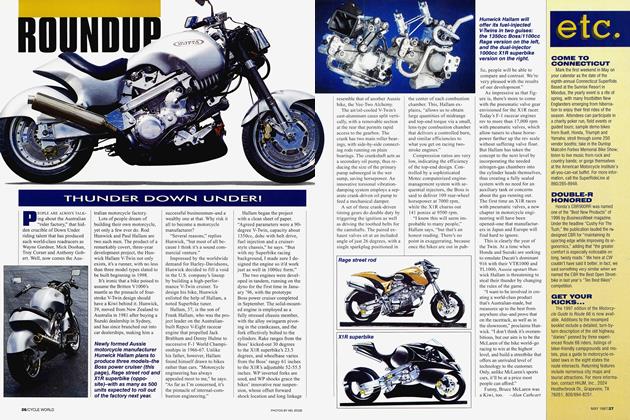

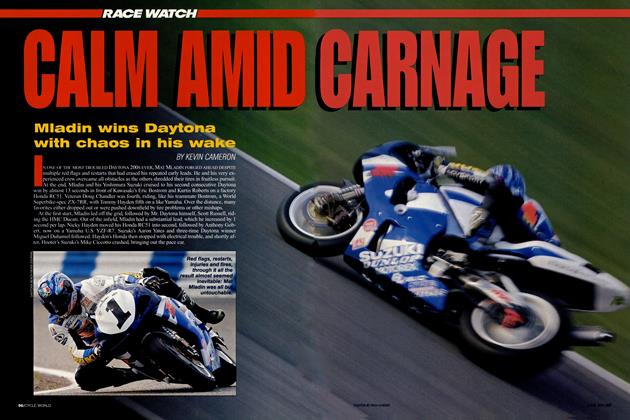

I COULD HEAR THE DEEP DRONE OF THE LEADER'S G50 Matchless, down on the apron where so many classic racing competitors ride—the short way around Daytona's big bowl. But up high on the banking, moving visibly faster, came another machine, higher in pitch, sweeping past start-finish and into the lead. This was the highly developed Honda CB450 of Todd Henning, an outsider's bike ridden by vintage racing's bestknown outsider. Henning went on to win Premier 500, vintage racing's top class, in 1994. And he has won it each year since, beating legendary Singles and multi-cylinder racebikes in the process.

Henning’s 450 has been decried as a “junkyard dog” by vocal elements in classic racing. It is, they imply, a low-status homebuilt that ought never be allowed to compete with pukka purists’ mounts like the Matchless, Nortons or ex-factory Benellis and MV Agustas. The impressive fact that this one-man team can win these races with a self-developed, 30-year-old streetbike is disregarded.

Coming to roadracing at an age when most Pros have quit, Henning threw himself energetically into campaigning readily available vintage two-strokes like the 250cc Yamaha TD1-C. He was soon successful-maybe too successful. His

combination of seriousness, forceful riding and the reliability of his machines racked up a long list of championships.

But to an influential few, two-strokes are the Dark Force, motorcycling’s shameful illegitimate son, whose picture should be turned to the wall. Two-strokes, they believe, ruined the classic era, forcing the elegant British Singles and the howling MV Multis out of the sport. The truth is considerably less dramatic: The British factories quit GP racing in 1954 for ordinary financial reasons, long before any twostroke challenge. MV’s racing days were numbered after the 1971 death of their patron, Count Domenico Agusta. But emotion brooks no argument.

Henning’s personal style is laconic and refreshingly candid. A lean, tall man aged 46, he until recently wore his hair long, pulled back in a 1970s ponytail. In the first years, his leathers sported a western fringe, but others claimed it was costing him speed. Back-to-back dragstrip tests showed a 3 percent horsepower penalty for the fringe so, äs he says, “Out came the scissors.” Anyway, the more races Henning won, the more off-track opposition he faced, in the form of fresh rules and procedures. Okay, he would take the hint and race four-strokes. Since G50s aren’t common and MV Agustas are beyond budget, he had to seek the four-stroke equivalent of his workfiorse TD1-C. He found it in the plentiful, cheap Honda 350 and 450. Never state-of-the-art as streetbikes, these machines would have to be pushed far to become successful racers. Although Henning had no way of knowing it then, beating classic racers with Honda streetbikes would irritate the vintage establishment just as much as doing it with two-strokes.

Every race team needs an industrial base to drive it. MV had Count Agusta’s personal fortune and the income of his helicopter empire to back it. Mainstream producers had worldwide sales of streetbikes to power their racing efforts. Henning has his own energy and what he can squeeze out of a 1916 two-bay auto-service garage business at the tip of Cape Cod, in Massachusetts.

Henning’s development of the Honda 450 from streetbike to Premier 500 race winner is proof that engineering belongs to anyone who needs it and wants it. The first, relatively easy horsepower increases pushed the stock chassis hard enough to make it very dangerous at high speed. He knew that Marly Drixl, a Swiss constructor, had built a few birdcage-style racing chassis for the 450 engine during the 1960s, making such a chassis legal for a 450 vintage bike. This “Drixton” chassis, carrying the engine much farther

forward than stock, would stabilize the bike by loading the front wheel. Where would he get one? Known owners weren’t selling; vintage racers Kurt Liebmann and Pete Johnson were riding theirs. Combing the world with his phone, Henning located an Irish builder willing to make the chassis. He sent money with his order.

The 450 engine is typical of Honda practice in the mid1960s. Air-cooled, it required a wide, 78-degree valve angle to get cooling air between its two massive camboxes, plus accommodate valve operation by unique torsion-bar valve springs and rockers. The small, deep combustion chambers have excess surface area that gathers heat, making the engine run very hot. Available high-compression pistons didn’t have the compression (an advertised 12:1 measured in at an actual 9:1) or had high, church-steeple domes that interfered with combustion.

Henning, with machining by Dave Gilbert of DCM in Framingham, Massachusetts, twin-plugged the heads. This speeded combustion. Next step was to make proper pistons-ones that would force fuel-air mixture into fastburning open space near the sparkplugs but fit tightly against the head elsewhere, leaving only safe mechanical clearance. Close-ratio gears had to be found. The torsion bars had to be replaced with higherperformance conventional valve springs. Megacycle provided the cams. Each fix, raising the engine to a new performance level, provoked yet other problems. Again and again, the bike has had to be raced with such problems because development moves in expensive, time-consuming steps, not fanciful leaps.

Henning gathered opinions and information from a circle of friends he had accumulated over the years. Gilbert was only one of many “uncles” he called upon for ideas or services. Every successful builder-racer has such a circle of “enslaved” interested parties, who contribute to his success in return for the satisfaction of seeing their contributions on the start line.

Henning is a skeptical pragmatist, with limited respect for the majority opinion. His bikes have never been beautiful because there has never been time to make them right and to have them painted picture-perfect. When the Drixton 450 finally appeared at Daytona in 1994, gleaming in its Irish-made chassis kit with professionally painted fairing, tank and seat, Henning said, “This isn’t me.” All his previous racebikes had sported the operational look; they were goers, not lookers. He does nothing to engines or chassis except what he believes will be costand time-effective. The pipes he has developed through hundreds of dyno runs are made of J.C. Whitney tubing bends, pieced and welded together. No stainless, no titanium, no decorator carbon-fiber. If it works, it has a place on the bike.

He consults the uncles, but makes his own decisions in a kind of triage of solutions. His dollar has to go far, and everything has to be dead-reliable. He’s doing this for one reason only: to win. He’s not interested in sophistication for its own sake. He doesn’t let creeping craftsmanship turn one-hour jobs into all-day perfection marathons. Get those bikes into the van and go! One running machine on the start line is worth all the good ideas in the world, halffinished in the shop.

Starting with an Eraldo Ferracci-ported 450 head, Henning moved on with a borrowed flowbench to quickly become his own airflow expert. The uncles had their say, but it was Henning who tirelessly ported one head after another, baselining and re-checking heads that track use had proven to be either very good or very bad. Here is one powerful essence of successful engineering: Have the energy and motivation to plow through enough intelligent tests to get the information needed; endure boring hours and days of learning nothing, just to earn those few intense moments of discovery whose sweetness makes it all worthwhile. Somewhere in this equation, Henning finds time to live and to enjoy his family. The garage business and his racing-parts mail-order operation demand the rest of his time.

Item by item, he has worked through to optimum values-for intake length, cam timing, exhaust design, piston-crown shape. Exhaust rocker arms are a problem on the 450, lasting as little as two to three hours before they are scuffed and must be replaced lest they bring down the whole engine. Various oils, oil feeds and rocker hard-coatings were tested to achieve a workable solution. In one case, he fabricated 13 alternative exhaust systems and trucked off to the trusty Dynojet dynamometer for a day-and-a-half of testing-only to find that the system he began with was superior to all his experiments. Henning was philosophic about this, but not really pleased.

Lightweight cranks ought to work, he was told. They lost 500 revs that came back with the heavy crank. Truth can be surprising, like the ugly port that flows big air. The current bottom line is 60 rear-wheel horsepower at 10,500 revs. Every one of them has been earned. Disaster struck just before Daytona 1994, when at a warm-up event five engines destroyed themselves. It looked like cancellation time. But with day-and-night work, pressing two motel rooms into service as shops, and with usable parts scrounged from area salvage yards by far-ranging volunteers, the bikes were made whole again and races were won.

As we drove to lunch in his van one day last fall, I could see one obvious source of his bikes’ usual reliability. With the van’s engine just above idle, he had the clutch in with almost no slip and we were rolling. He explained, “This van has 260,000 miles on it, and I got 160,000 from the first clutch. It’s a lot more pleasant sitting here driving than it is lying underneath with tools in my hand.” This kind of care made his TD1-C last a remarkable four trouble-free seasons.

“If I get in the lead and can pull away, I start short-shifting,” he remarked. Resource conservation!

In tuning, he stays a careful distance from the edge, making speed by having the right compression and ignition timing-not by bone-lean jetting, not by rod-stretching revs.

Henning is a racer because he likes riding and urgently wants to win races.

“I learn something new every time I ride. I love it, I can’t wait to get back on a bike,” he says with his usual frankness.

On the track, he is smooth and economical rather than sudden, crafty rather than stylish. His opponents know he is always planning their defeat, and they respect, even fear, this. At one particular event, Henning knew his closest competitor would be tough, but through careful observation realized how to tell when this rider’s bike was at its very limit. In the race, he drafted this man, pushing steadily harder, hoping for the gift of a useful mistake-and watching for the tell-tale symptom. It did appear, indicating his opponent was at the edge with nothing left. He eased on by for the win. And no, Henning does not feel the need to share with us the opponent’s name or his mistake-after all, he has to race the man again.

As a boy in Miami, Florida, Henning looked at racing from afar, but could not afford to participate. When he was 16, he rode away on the Honda 450 he owned at the time, spending the next years working in cycle shops in Canada and across the U.S. The reverberations of this independence are audible in his conversation, visible in his life and implicit in his approach to racing. All problems can be solved, but only some in this lifetime, and fewer yet at affordable cost. Pick ones that can be solved and get to work.

“I wish I had the guts to just go with my intuition,” he says of engine development, “because it sure is a helluva lot quicker than the dyno and the flowbench.” That intuition comes from a lifetime of all kinds of engine work, and many hundreds of races run and then carefully analyzed.

There is a grain of truth in that “junkyard dog” label issued by Henning’s detractors, for many of the parts in his bikes are used. But it also implies that Henning’s machines and achievements are somehow valueless. The dollar value of an MV or a Manx Norton is put there by the willingness of able buyers to pay well for a piece of history. The historic value was put there by great engineers and great riders in the usual way. The value in Henning’s Hondas is put there in exactly the same way-by outstanding engineering and hard riding. He is making his own history, whether critics like it or not. The result? Motorcycles able, under the rules of vintage racing, to perform the real job of any racebike, classic or modem. To win. El