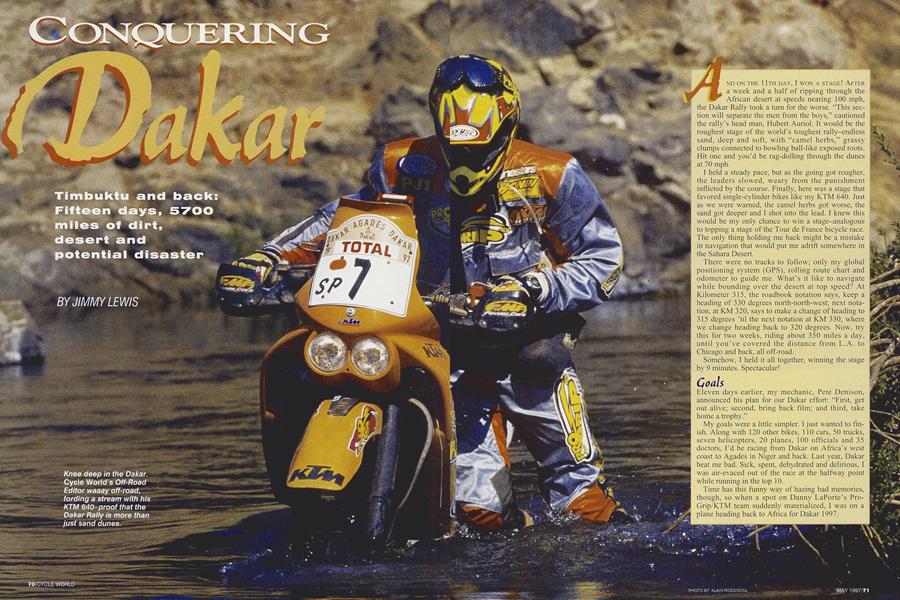

CONQUERING Dakar

Timbuktu and back: Fifteen days, 5700 miles of dirt, desert and potential disaster

JIMMY LEWIS

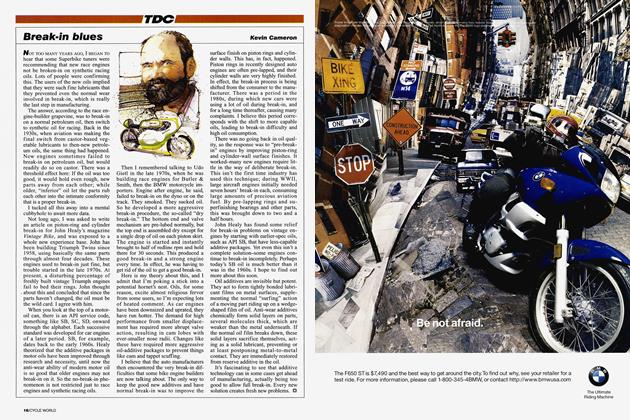

AND ON THE 11TH DAY, I WON A STAGE! AFTER a week and a half of ripping through the African desert at speeds nearing 100 mph, the Dakar Rally took a turn for the worse. "This section will separate the men from the boys," cautioned the rally's head man, Hubert Auriol. It would be the roughest stage of the world's toughest rally—endless sand, deep and soft, with "camel herbs," grassy clumps connected to bowling ball-like exposed roots. Hit one and you'd be rag-dolling through the dunes at 70 mph.

I held a steady pace, but as the going got rougher, the leaders slowed, weary from the punishment inflicted by the course. Finally, here was a stage that favored single-cylinder bikes like my KTM 640. Just as we were warned, the camel herbs got worse, the sand got deeper and I shot into the lead. I knew this would be my only chance to win a stage-analogous to topping a stage of the Tour de France bicycle race. The only thing holding me back might be a mistake in navigation that would put me adrift somewhere in the Sahara Desert.

There were no tracks to follow; only my global positioning system (GPS), rolling route chart and odometer to guide me. What’s it like to navigate while bounding over the desert at top speed? At Kilometer 315, the roadbook notation says, keep a heading of 330 degrees north-north-west; next notation, at KM 320, says to make a change of heading to 315 degrees ’til the next notation at KM 330, where we change heading back to 320 degrees. Now, try this for two weeks, riding about 350 miles a day, until you’ve covered the distance from L.A. to Chicago and back, all off-road.

Somehow, I held it all together, winning the stage by 9 minutes. Spectacular!

Goals

Eleven days earlier, my mechanic, Pete Denison, announced his plan for our Dakar effort: “First, get out alive; second, bring back film; and third, take home a trophy.”

My goals were a little simpler. I just wanted to finish. Along with 120 other bikes, 110 cars, 50 trucks, seven helicopters, 20 planes, 100 officials and 35 doctors, I’d be racing from Dakar on Africa’s west coast to Agades in Niger and back. Last year, Dakar beat me bad. Sick, spent, dehydrated and delirious, I was air-evaced out of the race at the halfway point while running in the top 10.

Time has this funny way of hazing bad memories, though, so when a spot on Danny LaPorte’s ProGrip/KTM team suddenly materialized, I was on a plane heading back to Africa for Dakar 1997.

Anxiety

This 19th-annual running of what started as the Paris-toDakar Rally is now an all-Africa event. Organizers were busy avoiding hostile countries and religious wars, so for the first time the course was a loop affair that began and ended in Dakar, the capital city of Senegal.

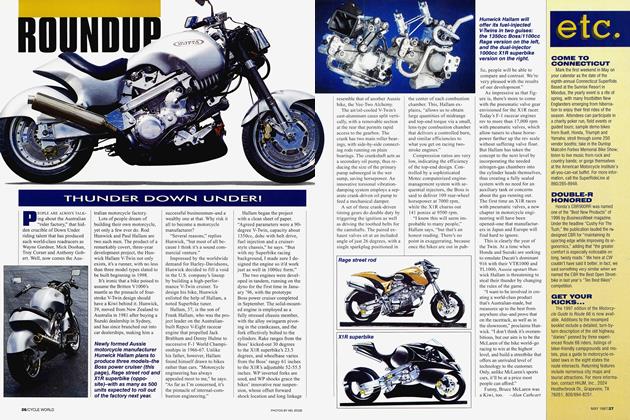

My nerves were tight as piano strings before the start. I would not see my KTM 640 Rally until just hours before impound. Based on the Austrian company’s 620 dirt Thumper, it was rigged for rally duty with a 12-gallon fuel capacity (7 in the main tank, 2.5 each in the side tanks), and a frame-mounted fairing that shielded the mapbook holder, GPS computer and electronic odo. Unfortunately, when I deplaned in Dakar, the bike was still on a boat from France. And have I mentioned that little problem with my FIM license? For five days in Senegal preceding the event, you could count the hours of sleep I’d gotten on one hand and hold the amount of food I’d eaten in the other.

Luckily, in the hour I had to work on the bike before impound, I was able to affix my GPS and mount a set of Michelin Mousse-equipped wheels (a replacement for inner tubes, Mousse is a foam-rubber insert that eliminates punctures). Otherwise, the KTM was box-stock-it was literally rolled off the production line onto a ship, and sent to Dakar. I’d have to use the 100 miles of riding to the first special test as break-in.

Into Africa

A lot happened in the first four days of the rally. Four-time Dakar winner Stephane Peterhansel, often called the world’s best off-road rider, set an untouchable pace on his works Yamaha 850cc Twin, building up a lead of more than an hour. Others were crashing out or breaking their bikes in an attempt to keep “Peter” in sightamong them former motocross world champions Heinz Kinigadner and my teammate Danny LaPorte. Casualties to the powerhouse KTM factory team included two broken wrists, a torn knee and a separated shoulder. Remaining were KTM riders Thierry Magnaldi, now a distant second, and Spaniard Jordi Acarons sitting in third. Cagiva rider Oscar Gallardo was in fourth and I had moved up to fifth position, two hours off Peterhansel’s pace with my cautious and calculated riding.

As the rally crossed the Sahel Desert region with its monkeys, baboons and giant boars, things were going better than planned. Top five overall, plus I was eating and sleeping as normally as I could, given that a sleeping bag is never a bed. And the bike was still in excellent condition.

Air Lewis

It was hot. Nearly 100 degrees in the middle of western Africa’s winter, even in the shade. And in the desert, shade is at a premium. One of my best strokes of luck during the rally came at the end of Day 5, when I was riding through the bivouac looking for my mechanic, Pete. The pilots of a C-130 cargo plane waved me over. Sitting under the wing, in the shade, they asked me if I’d like a beer. Beer and shade? Well, Mrs. Lewis didn’t raise a dummy. One of the pilots handed me a Heineken, the first cold thing I’d touched since leaving the U.S. The Safair Hercules, which transported TV equipment and journalists, was one of 20 planes that made up the rally’s lifeline. The South African aircrew literally took me under their wing, giving me shade, a safe spot to pitch my tent each night and some cheerful friends who traded priceless commodities like water, food and shower time for my team T-shirts.

Halfway Home

Steady riding got me safely to Agades, the halfway point. The Sahel and its greenery had changed to the Tènèrè’s desert and camels. Eight days of riding, moving up to fourth place, dodging camels and goats, avoiding ditches and sandblindness in the dunes, not dropping the bike in the fesh-fesh (silt) or losing my way and ending up in Timbuktu-unless, of course, that’s where the routebook said I was supposed to be. Pete was doing a fantastic job maintaining my faithful 640, and gave it an extra-special once-over at the halfway stop, checking every nut, bolt and frame tube for damage. He kept thanking me for being so easy on the bike. Hey, no problem; the last thing I wanted to do was break down out in the desert, quite literally the middle of nowhere. Just in case, the KTM chase trucks-two giant 4x4s and one 6x6 filled with wheels, parts and tools-were still showing up in a timely fashion, the sleep-deprived drivers only slightly worse for wear.

Eastbound

Dakar is not without its superstitions, and you don’t dare talk about the finish when you’re past the halfway marker. Thankfully, the pace of the rally was relaxed due to Peterhansel’s insurmountable, vice-like grip on the lead. KTM’s Magnaldi and Acarons, and Cagiva rider Carlos Sotello were taking turns winning stages as Peterhansel was content to follow and ride safe. I

was doing the same, locked in a

battle for third, fourth and fifth

place. In front of me, Gallardo on

his Italian V-Twin; behind me,

David Castéra on a Yamaha identi-

cal to Peterhansel’s. Big problem

for me was the speeds these guys set on the flat, sandy portions of the course. Here, the Yamaha and Cagiva had a huge advantage. With just a few minutes separating the three of us, I was tom between losing a position or pushing the bike past its limit. That was the fate of Magnaldi, who blew two motors during the rally. It’s impossible to keep up

with the full-tilt Twins on a Single.

TV Nation

Television makes Dakar as big as it is. With live prime-time coverage every night in France and Japan, plus various other

venues around the world, including Speedvision here in the

U.S., its ratings are astronomical-except, of course, among America’s stick-and-ball fanatics. For five days, I carried a small television microphone inside my helmet so I could commentate while riding, followed by an acrobatic helicopter, brave cameraman hanging on the skids. On the night of my stage win, I did a live interview for French TV.

Pre-interview, I spent a few extra seconds under the C-

130’s wing-mounted, water-in-a-bag shower so Mom would

be proud of her son on TV.

Doctor Dread

To say that I’m scared of needles would be an epic under-

statement. But during the rally, my routine consisted of a

stop at the medical tent for the ailment of the day. To combat everything from early-race anxiety to the ever-popular stomach malfunctions, there wasn’t a pill, cream, massage or bit of advice I didn’t take. Be it for treatment of monkey butt (don’t ask), athletes’ foot, loss of feeling in my hands or general stiffness, the doctors in the orange tent got to know

me on a first-name basis. Some days, it was difficult to walk

into the tent, littered as it was with riders and drivers, bodies

and spirits broken, their Dakars over. Of the 126 motorcycle

starters, only 58 would make the finish,

Crashing

It’s a given: Everybody crashes during the rally. On the third day, I fell three times, small tip-overs caused by fatigue. My worst get-offs came on the 12th day, the day after winning the stage. My excuse was a front Mousse that began to disintegrate 500 kilometers into a 575-km day. I fell three times, breaking my front and side fuel tanks in a spectacular cartwheel through some ditches, followed by a 70-mph slide-out. No serious injuries, but I lost 20 minutes fixing the bike. That same day, second-place Acarons hit a dog and was forced to retire, so without the crashes, I would have been in third. As it was, I gave up the place to Castéra. The only other time that the bike and I parted company was in the extremely soft dunes of Mauritania, but at least the bike stayed upright, its front wheel stuck in the sand while I tumbled over the front fender. In Dakar, that doesn’t count as a crash.

Yamaha vs. KTM

In a move to cut down the cost of racing, mies state that a Dakar bike cannot be a “works” machine. Super Production is the premier class, reserved for bikes that have extensive modifications to production-based motors and frames, but with a value not to exceed $40,000. I doubt that 40 large would buy you the Yamaha Peterhansel was riding, a purpose-built Dakar weapon in titanium, aluminum and carbonfiber. KTMs like mine can be ordered directly from the

factory for a “measly” $ 16,000.

The whole issue of factory involvement, Singles vs. Twins, weight limits and the laying out of a course that is fair to both types is a giant can of worms that nobody seems to have an answer for.

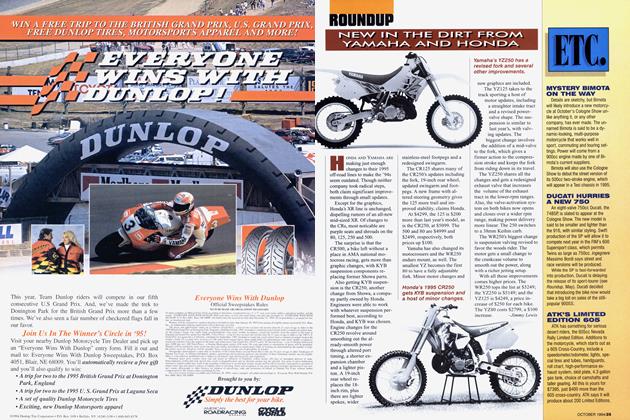

Finishing

After seemingly endless days of rising for the 4 a.m. start and riding until late in the afternoon, I was happy to see my odo counting down the final kilometers. Then, I rounded a comer and headed down a silty dirt road with the choking smell of dead fish in the air. The ocean appeared and I was overwhelmed with the realization that what was once only a fantasy was now an achievement-Td finished the Dakar. Right after a big, top-three-only party on the podium, I rolled up, fist raised, smile a mile wide. First single-cylinder, fourth overall and feeling like a dream had just come tme. I got my trophy, Pete got his pictures and we were both very much alive. Mission accomplished. 0