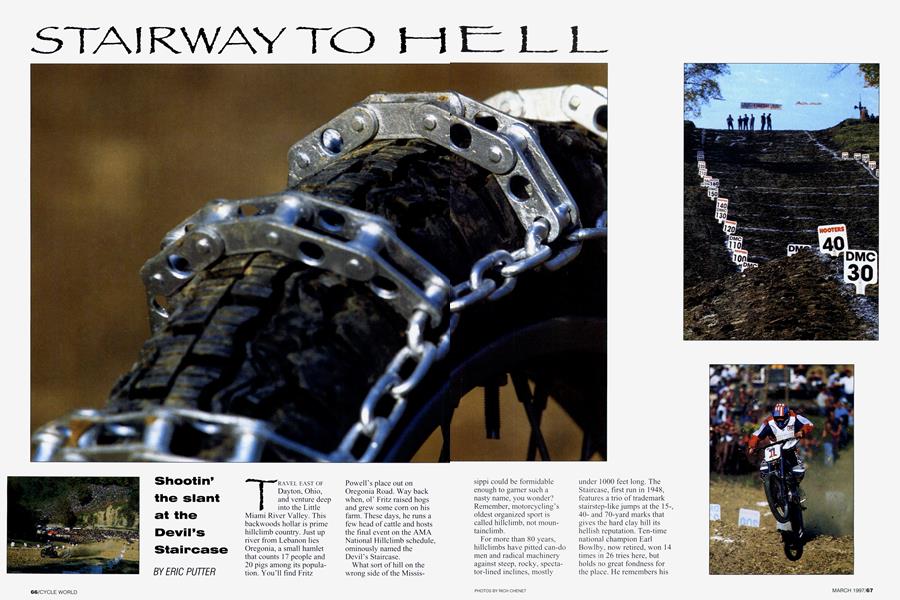

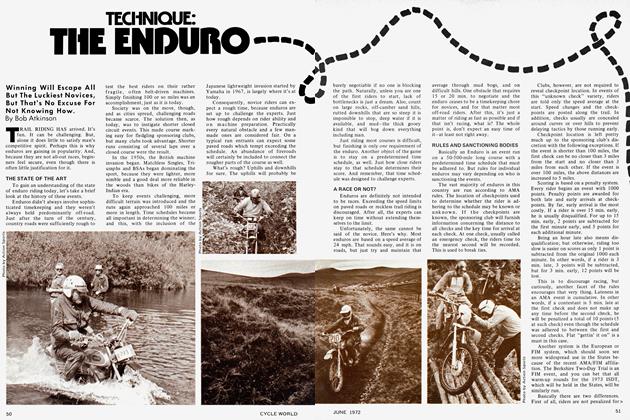

STAIRWAY TO HELL

Shootin' the slant at the Devil’s Staircase

ERIC PUTTER

TRAVEL EAST OF Dayton, Ohio, and venture deep into the Little Miami River Valley. This backwoods hollar is prime hillclimb country. Just up river from Lebanon lies Oregonia, a small hamlet that counts 17 people and 20 pigs among its population. You’ll find Fritz

Powell’s place out on Oregonia Road. Way back when, ol’ Fritz raised hogs and grew some corn on his farm. These days, he runs a few head of cattle and hosts the final event on the AMA National Hillclimb schedule, ominously named the Devil’s Staircase.

What sort of hill on the wrong side of the Mississippi could be formidable enough to garner such a nasty name, you wonder? Remember, motorcycling’s oldest organized sport is called hillclimb, not mountainclimb.

For more than 80 years, hillclimbs have pitted can-do men and radical machinery against steep, rocky, spectator-lined inclines, mostly

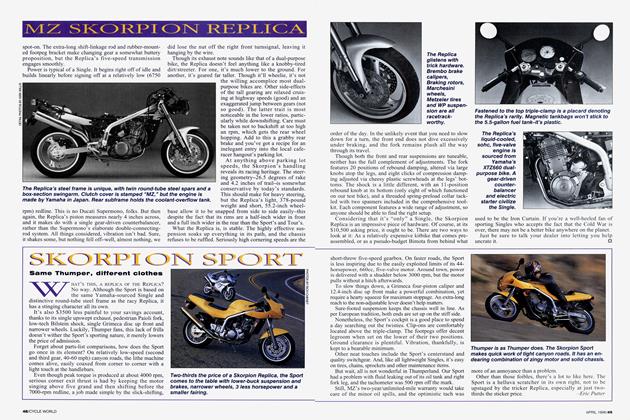

under 1000 feet long. The Staircase, first run in 1948, features a trio of trademark stairstep-like jumps at the 15-, 40and 70-yard marks that gives the hard clay hill its hellish reputation. Ten-time national champion Earl Bowlby, now retired, won 14 times in 26 tries here, but holds no great fondness for the place. He remembers his first attempt in 1965:

“The first three people who rode the hill were taken to the hospital because of that real severe first step,” he says. “I didn’t like the hill because it was dangerous. The stairs were so severe, if you didn’t get the throttle shut off in time, they threw you so far in the air you couldn’t set up for the next one.”

As the man-made steps indicate, this is not a raw, natural course like some on the 10-race AMA calendar. The Staircase is a groomed run measuring just 360 feet long and 25 feet wide. Nobody knows the hill’s incline for sure, but one racer reports it is so steep he has to climb the hill on all fours during scouting hikes.

Yes, riders must walk-or crawl-the hill for a pre-event survey of the course. There’s no practice in this game; a pair of runs is all you get. The format is simple: Fastest man to the top wins.

Here’s how top-gun Paul Pinsonnault does it on his Honda CR500.

First, he pre-warms his engine before pushing the bike up to the start. Once positioned in the starting pit, he has two minutes to begin his run. He holds the throttle wide-open before dumping the clutch. All 400 pounds of bike and rider accelerate to top speed in the first 100 feet. Crouched over the handlebar the whole way, he keeps it in second gear and almost never fans the clutch. “I’m not a clutch player,”

Pinsonnault says. “If you have to grab the clutch, you’re going too slow already. It’s all about body English and throttle control. I squeeze the bike between my legs, hang on with my ankle bones, my feet, my knees, everything-it’s a full-body thing. I’ll do anything to keep the rear wheel on the ground and driving.”

For spectators, some 10,000 strong, there are just two classes to follow. The 540cc ranks are split between old British verticalswins that have been class mainstays for decades and modem twostroke motocross-based machines like Pinsonnault’s Honda. In the 800cc class, HarleyDavidson Big Twins reign supreme over challenges from Japanese inlineFours. The MXers are basically stock with impossibly elongated swingarms; Twins in both classes are stuffed into a variety of custom frames rigged to various suspension pieces. All run on a mix of nitromethane and alcohol.

History was made in the 540cc class. By finishing second, Pinsonnault etched his name in the record books as the only hillclimber ever to win four championships in a row. But it was Richard Soter III, on a BSA, who took the Staircase win, thundering up the hill in 7.97 seconds. The 800cc class championship was anti-climactic, as secondgeneration racer Lou Gerencer Jr. had already captured his third title with a win at the previous event. But defending winner Steve Dresser took home the biggest portion of the $23,000 Devil’s Staircase purse with a 7.36-second pass for the victory.

While Dresser made off with a decent chunk of change, it was still just that-change. Although hillclimbing is called a professional sport, there’s no chance of making a living racing full-time. Tom Riser, a 40-year veteran of the sport, says, “When you decide to go hillclimbing, you figure out how much you’re gonna lose and keep it down to a minimum, because you’re not gonna make any money. I lose money as soon as I leave the house.”

If anyone’s making money at the Devil’s Staircase, it’s farm-owner Fritz Powell-though he’s not looking to make a killing off his rental fee. A quiet, religious man, Powell was never crazy about the meet’s name, but came to a handshake agreement with the Dayton Motorcycle Club to stage the event on his land.

“The old man comes around on race day to survey the crowd and rider turnout in order to decide on a fee,” says club historian Charlie Rees. “When the sun is shining and the crowd is lining the hills, Fritz says, ‘You guys look like you did pretty well this time,’ and asks for a decent amount. When we don’t make as much money, he gives us a break. That sort of kindness has kept us going.”

Next time you’re out in hillclimb country near Oregonia, be sure to stop by ol’ Fritz’s place and say thanks. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Hopwood Chronicles

March 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsHow Many Bikes Do You Really Need?

March 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPractical Men

March 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1997 -

Roundup

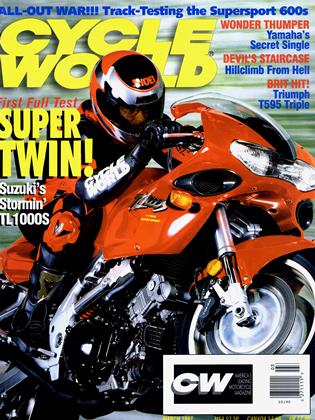

RoundupYamaha Shows Wonder Thumper!

March 1997 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupTraction Calling

March 1997 By Don Canet