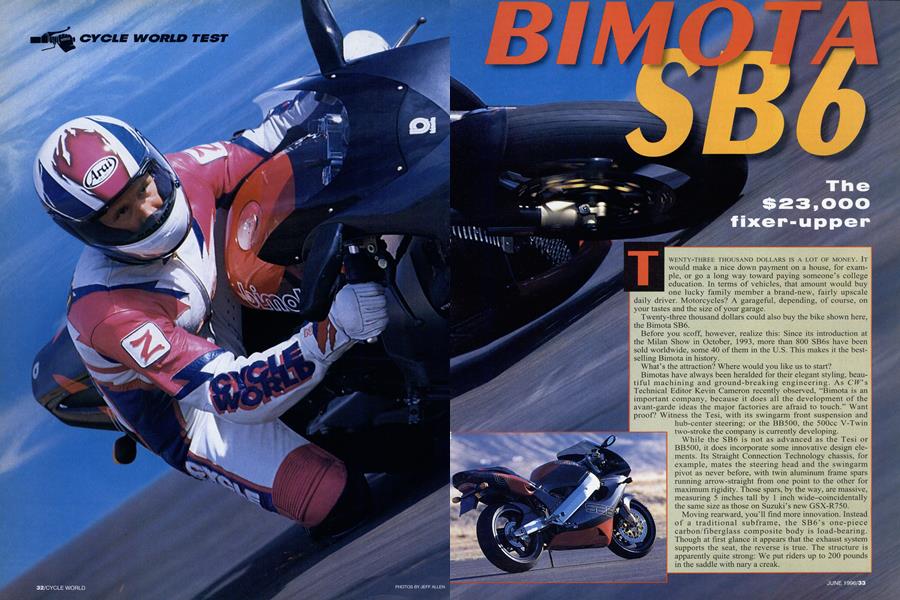

CYCLE WORLD TEST

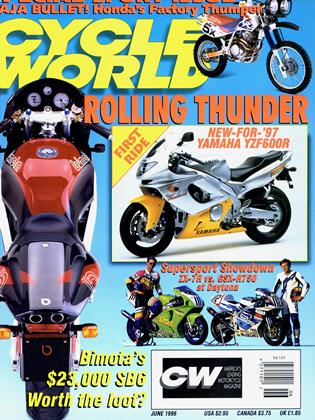

BIMOTA SB6

The $23,000 fixer-upper

TWENTY-THREE THOUSAND DOLLARS IS A LOT OF MONEY. IT would make a nice down payment on a house, for example, or go a long way toward paying someone's college education. In terms of vehicles, that amount would buy one lucky family member a brand-new, fairly upscale daily driver. Motorcycles? A garageful, depending, of course, on your tastes and the size of your garage.

Twenty-three thousand dollars could also buy the bike shown here, the Bimota SB6.

Before you scoff, however, realize this: Since its introduction at the Milan Show in October, 1993, more than 800 SB6s have been sold worldwide, some 40 of them in the U.S. This makes it the bestselling Bimota in history.

What’s the attraction? Where would you like us to start?

Bimotas have always been heralded for their elegant styling, beautiful machining and ground-breaking engineering. As CJT’s Technical Editor Kevin Cameron recently observed, “Bimota is an important company, because it does all the development of the avant-garde ideas the major factories are afraid to touch.” Want proof? Witness the Tesi, with its swingarm front suspension and hub-center steering; or the BB500, the 500cc V-Twin mm-1 two-stroke the company is currently developing.

While the SB6 is not as advanced as the Tesi or BB500, it does incorporate some innovative design elements. Its Straight Connection Technology chassis, for example, mates the steering head and the swingarm pivot as never before, with twin aluminum frame spars running arrow-straight from one point to the other for maximum rigidity. Those spars, by the way, are massive, measuring 5 inches tall by 1 inch wide-coincidentally the same size as those on Suzuki’s new GSX-R750.

Moving rearward, you’ll find more innovation. Instead of a traditional subframe, the SB6’s one-piece carbon/fiberglass composite body is load-bearing. Though at first glance it appears that the exhaust system supports the seat, the reverse is true. The structure is apparently quite strong: We put riders up to 200 pounds in the saddle with nary a creak.

The 4-1-2 exhaust system is also unusual, as it bends upward behind the engine and then again under the seat, its pair of mufflers exiting through the rear of the tailpiece. Heat shielding and screened louvers in the tail keep the rider’s derrière insulated from the hot exhaust.

Because the pipe resides in the space normally occupied by the rear suspension, the shock and its rising-rate linkage were moved up and to the right. This, in turn, caused the battery to be evicted from its traditional home; a pair of small, scooter-sized units now reside behind the twin headlights, along with the fuse box. Look to either side and you'll see the steering stops: a pair of rubber donuts around the fork tubes that bump against the frame spars. Clever.

Mass centralization is a term we’ve heard often in the past few years, and this is the key to the SB6’s chassis design. More and more manufacturers seem to be inclining sportbikes’ cylinder banks way forward in an effort to put more weight on the front wheel, yet the comparatively vertical cylinder layout of the SB6’s Suzuki GSX-R1100 engine actually helps in this instance, allowing the crankcase to be moved very close to the front wheel. This allows the airbox and fuel tank to be positioned farther down than normal, resulting in a very low center of gravity.

Another side-effect of the engine-and-chassis layout is a seat height a mere 29.8 inches off the ground. The seat is so low, in fact, that you reach up to the clip-on handlebars, eve though they grip the fork tubes beneath the top triple-clamp.

The end result of all this component juggling is a diminu tive motorcycle. The wheelbase measures a paltry 54.1 inch es, and dry weight is just 441 pounds. That’s shorter and lighter than most 600s!

This compactness does, however, have its downside. Go ahead and try to add oil to the engine-we dare you. Because the engine is packed so tightly inside the frame, there isn’t enough room behind the right-side frame spar for the stock oil-filler cap; a large, flush-mount Allen plug is used instead. The frame is relieved on the back side for additional clearance, but you still need small hands and a long funnel to top if off. Valve adjustments? Don’t ask.

This isn’t the only instance where design clashes with function, or where components were selected as much for their appearance as for how well they work. Good examples are the hinged axle clamps on the conventional 46mm Paioli fork (with carbon-clad legs for increased stiffness and, perhaps more importantly, beauty). Developed for endurance racing, this set-up normally allows mechanics to quickly change the front tire by dropping the axle, then twisting the fork legs so that the brake calipers clear the tire. Trouble is, on the SB6 the front fender is bolted to the fork legs, and even if it wasn’t, there isn’t enough clearance between the calipers and discs to rotate the fork legs out of the way. So you have to change tires the traditional way, by removing the calipers first. And even then, you have to remove the fender, because it covers the caliper mounting bolts.

Similar compromises abound. The steering damper is neatly tucked behind the right-side fairing upper, where it’s all but impossible to reach the adjusting knob. The rear ride-height adjuster is equally difficult to use, because there isn’t enough room to get a wrench on the locknut with the shock in place; you have to unbolt it first.

The one-piece seat/tank cover and onepiece fairing are lovely, but impractical.

Removing either is a lesson in patience and futility. The fairing is particularly tricky, as you have to spread the lower to slide it past the front wheel. (Bimota knows this, as evidenced by the three-piece fairing on the new YB9SRI.) A lock on the tailpiece hints at a storage area, but inserting the key and removing the seat squab reveals only the muffler mounting bolts, and enough space for your registration and insurance papers.

Fortunately, the SB6’s performance makes up for its quirks-or rather, it did once we got it dialed-in. To be painfully honest, the SB6 was originally slated for inclusion in last month’s “Ultimate Sportbike Challenge,” but fuel-delivery and carburetion problems delayed its appearance until now.

What was the problem? We wish we could tell you. Trouble is, we can’t put our finger on any one thing. During its stay, we fiddled with virtually every component having to do with the fuel system. In frustration, we replaced the entire tank (along with its petcock and breather hose), added the factory cool-air induction system ($113), and installed a Dynojet carburetor recalibration kit ($116). After numerous dyno runs, we finally settled on #120 main jets, compared to the mixture of # 125s and # 127s the SB6 employs in stock trim, and far smaller than the # 132s that

Southern California dealership Pro Italia Motors originally fitted.

This resulted in a bike that carbureted well throughout its rev range, and which produced 127.8 rear-wheel horsepower at its 9750-rpm peak. Bimota claims to have extracted 10 additional midrange ponies from the GSX-R motor, crediting larger diameter exhaust plumbing, and we would not dispute

this. Power comes on strong as low as 4000 rpm, which, combined with the bike’s light weight and short wheelbase, means it wheelies at virtually any speed above idle. Vibration is more noticeable on the SB6 than on a stock GSX-R1100, particularly under trailing throttle, probably due to the lack of bar-end weights. Engine noise is also more noticeable, as the stiff, one-piece body reverberates like a giant acoustic guitar. This is one motorcycle that’s louder sitting in the saddle than standing alongside.

Acceleration is ferocious, seemingly becoming stronger as speeds increase. The SB6 took just 10.49 seconds to cover the quarter mile, and clocked a top speed of 166 mph. It clearly would have been in the running in last month’s comparison test. Braking is equally impressive, with a pair of Brembo four-piston calipers grasping 12.6-inch cast-iron rotors. Between the short wheelbase and powerful brakes, the rear wheel lofts almost as often as the front.

In twisty going, the SB6 behaves much as its spec sheet suggests. Direction changes are instantaneous, with light, crisp steering rivaling any other sportbike. Unlike some of its competition, however, the SB6’s flickability comes with no concession to stability; the thing is rock-stable, even in triple-digit sweepers. How does it accomplish this uncanny blend of shortness and stability? Surely, its low center of gravity plays a chief role.

Suspension, however, is a mixed bag. The Paioli fork is fairly plush, soaking up small and large bumps equally well, but the Öhlins shock gives a rough ride no matter where its dials are set.

While some of this may be due to the painfully sparse seat padding, the shock’s soft spring no doubt is partly responsible. Stiffer springs front and rear would let the bike ride in the supple part of the suspension stroke, while also elim inating some of the chassis pitch experienced under heavy braking.

` As delivered, the SBb works best at a moderate sport-riding pace; slower, around-town going yields a harsh ride, while faster sport riding results in the chassis moving around more than we'd like. Racetrack testing saw the footpegs and fairing touch down-followed by editors backing off the throttle. Our insurance company doesn't take too kindly to writing $23,000 checks, you know.

So, what we have here is a bike that promises the world, and fails to deliver. It is not the first exotic vehicle to do so, and will not be the last. CW Contributing Editor Steve Anderson theorizes that with few exceptions, as cars surpass the $60,000 mark, they get progressively worse. Could that number be $20,000 for motorcycles?

There are two schools of thought regarding the SB6's flawed performance, both ironically expressed by people with vested interests in selling Bimotas. Bob Smith, presi dent of Pennsylvania-based importer Moto Cycle, says that Italian bike owners expect to have to spend some time and money dialing-in their mounts; they've already spent $23,000, he argues, so what's a few dollars more? Earl Campbell, owner of Pro Italia, takes the opposite view; he feels that given the SB6's lofty price tag, it should be fully sorted before the owner takes delivery. Who's right? You make the call.

The painful truth is that Bimotas have always been-and probably will always be-part kitbike. That’s the inherent nature of a motor vehicle with a short gestation period, particularly when it’s being built by a small company that pushes the technological envelope. Unlike larger manufacturers, which have the luxury of designing engines and chassis simultaneously, Bimota’s engineers cannot begin work on a new model until they have a power unit to work with-or at least have an idea of its dimensions. If some details are overlooked in the rush to reach production in a timely manner, then that’s the price you pay for exclusivity. In this case, $23,000. □

EDITORS' NOTES

SPENDING A COUPLE OF HUNDRED STREET miles in the saddle of the Bimota SB6 left me standing in awe. But while its high level of performance is certainly worthy of ovation, what really brought me to my feet was a tortured tush. The SB6’s seat may look sweet and swoopy, but its padding can’t be a whole lot thicker than the vinyl covering it. This I can’t stand for on any roadbike, sexy Italian or not.

Okay, so maybe I could put a little meat on my bony butt. A few portions of 1 inguine with clam sauce, you say, and I’ll be properly equipped to savor the SB6’s nimble handling, solid stability and wheelie-prone power delivery?

Now, there’s some food for thought: With the SB6 weighing-in at 441 pounds dry (a standard Suzuki GSX-R1100 tips the scales at 519), I could ingest Italian on a regular basis and still not eat into the Bimota’s impressive power-toweight ratio. That’s what I call a tasty proposition.

-Don Canet, Road Test Editor

How DO I LOVE THEE, SB6? LET ME count the ways. I love thee in spite of the pinched vacuum line that stranded me in Turn 3 at Willow Springs, forcing a humiliating ride back to the pits in the crash truck. I love thee in spite of the fuel tank breather hose that came loose and melted on the hot exhaust pipe during top-speed testing, resulting in a 68-mph reading on the radar gun. I love thee in spite of the stuck float needle, the clogged fuel tank breather valve, the crossed sparkplug wires, the loose plug cap and the fouled plug. I love thee in spite of the 14 Allen bolts that had to be unscrewed to remove the one-piece body and diagnose each of the aforementioned problems.

Not a single one of the difficulties we encountered with our testbike could, however, dissuade me from falling hopelessly in lust with the SB6. So what if it needs more troubleshooting than your average Space Shuttle launch? Call it a labor of love. -Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

A TWO-WHEELED TEASE IS WHAT THIS thing is. Long on promises, short on delivery. Fabulous, but also frustrating.

Oh, the basic goodness of the SB6 package isn’t in question, it’s just that the Bimota Boys back there in Rimini aren’t sweating the details like they should. No 1996 motorcycle-especially not one from a coachwork company charging a premium for its supposed build-quality-should be beset by the rash of glitches, tantrums and niggles our jinxed testbike displayed.

Between faxes to Italy, phone calls to the importers, numerous trips to the not-so-local Bimota emporium and, finally, a Don Canet jetting session on CWs dyno, it took six weeks to get the SB6 sorted. This, on a test unit loaned to the world’s largest motorcycle magazine. Private citizens, I wish you well; just remember, what you’re buying is a $23,000 kitbike. Good luck.

-David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

BIMOTA

SB6

$22,950

View Full Issue

View Full Issue