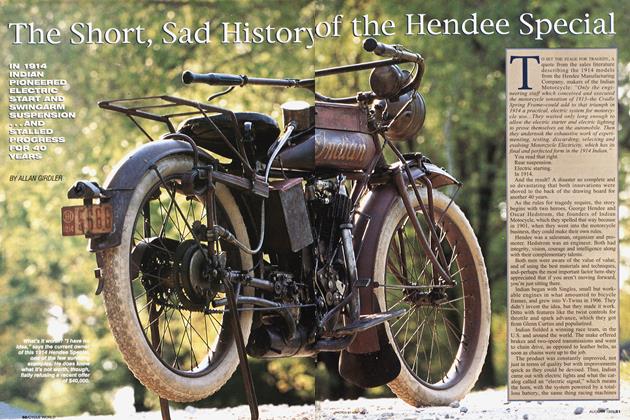

MILITAIRE AND MILIRTOR

ALLAN GIRDLER

Before you build a better mousetrap, be sure the public doesn't like mice

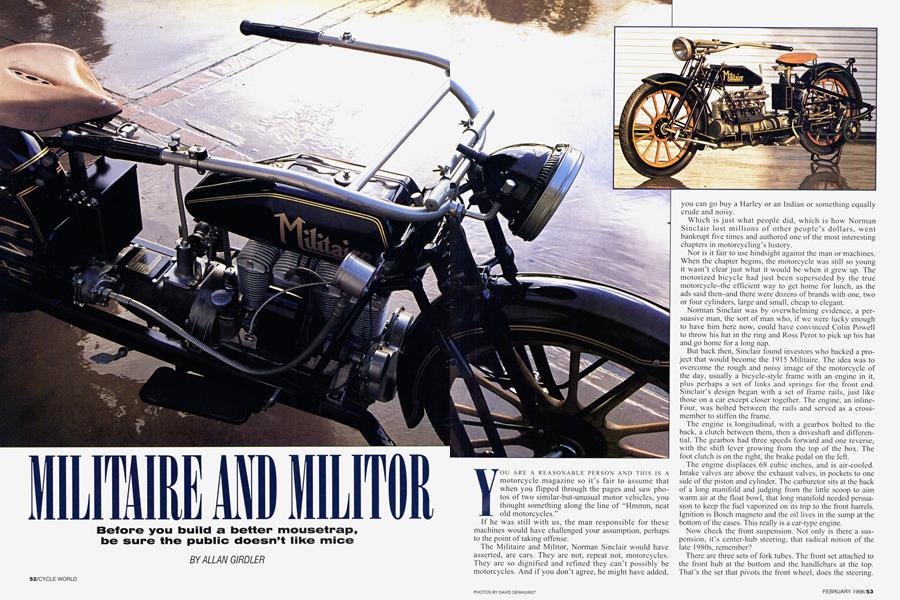

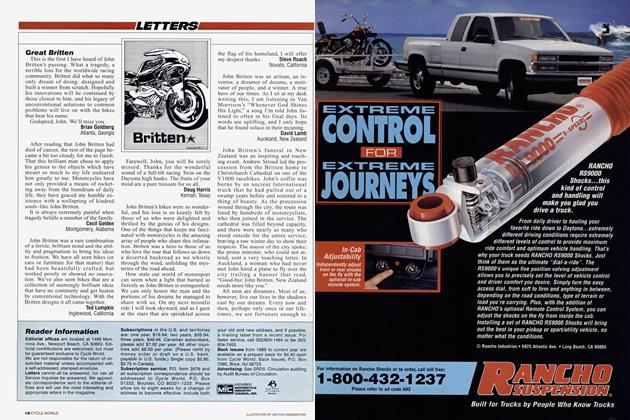

YOU ARE A REASONABLE PERSON AND THIS IS A motorcycle magazine so it's fair to assume that when you flipped through the pages and saw photos of two similar-but-unusual motor vehicles, you thought something along the line of "Hmmm, neat old motorcycles."

If he was still with us, the man responsible for these machines would have challenged your assumption, perhaps to the point of taking offense.

The Militaire and Militor, Norman Sinclair would have asserted, are cars. They are not, repeat not, motorcycles. They are so dignified and refined they can't possibly be motorcycles. And if you don't agree, he might have added,

you can gO buy a Harley or an Indian or something equally crude and noisy.

I1~J1~J. Which is just what people did, which is how Norman Sinclair lost millions of other people's dollars, went bankrupt five times and authored one of the most interesting chapters in motorcycling's history.

INor is it lair to use hindsight against the man or machines. When the chapter begins, the motorcycle was still so young it wasn't clear just what it would be when it grew up. The motorized bicycle had just been superseded by the true motorcycle-the efficient way to get home for lunch, as the ads said then-and there were dozens of brands with one, two or four cylinders, large and small, cheap to elegant.

Norman Sinclair was by overwhelming evidence, a per suasive man, the sort of man who, if we were lucky enough to have him here now, could have convinced Cohn Powell to throw his hat in the ring and Ross Perot to pick up his hat and go home for a long nap.

But back then, Sinclair found investors who backed a pro ject that would become the 1915 Militaire. The idea was to overcome the rough and noisy image of the motorcycle of the day, usually a bicycle-style frame with an engine in it, plus perhaps a set of links and springs for the front end. Sinclair's design began with a set of frame rails, just like those on a car except closer together. The engine, an inline Four, was bolted between the rails and served as a cross member to stiffen the frame.

The engine is longitudinal, with a gearbox bolted to the back, a clutch between them, then a driveshaft and differen tial. The gearbox had three speeds forward and one reverse, with the shift lever growing from the top of the box. The foot clutch is on the right, the brake pedal on the left.

`Ihe engine displaces 68 cubic inches, and is air-cooled. Intake valves are above the exhaust valves, in pockets to one side of the piston and cylinder. The carburetor sits at the back of a long manifold and judging from the little scoop to aim warm air at the float bowl, that long manifold needed persua sion to keep the fuel vaporized on its trip to the front barrels. Ignition is Bosch magneto and the oil lives in the sump at the bottom of the cases. This really is a car-type engine.

Now check the front suspension. Not only is there a sus pension, it's center-hub steering, that radical notion of the late 1980s, remember?

There are three sets of fork tubes. The front set attached to the front hub at the bottom and the handlebars at the top. That's the set that pivots the front wheel, does the steering. The second set goes to the horizontal strut that runs through the bearing in the center of the hub. At the outboard ends, the strut joins links and a pair of angled leaf springs anchored to the front extensions of the frame rails. This second set lets the wheel go up and down. The third set is to brace the pair of steering heads-yes, a pair-by linking the steering heads with the frame rails. The frame, so to speak, is horizontal. The fuel tank is supported by a tube between it and the engine, that’s all.

Moving back, we come to...a set of parking wheels?!

Yup. The ads for the Militaire always showed a welldressed man, suit and hat, in refined surroundings, tipping his hat to ladies and gentlemen of equal class. We can fairly judge here that Sinclair didn’t like getting his shoes muddy or dusty, which is what happened back then when the motorcycle rider put his feet down. But the Militaire rider didn’t sully himself with such vulgarities. Instead, there are those two little wheels, which we’ll call parking wheels

instead of training wheels. See the pedals aft of the floorboards? One pedal lowers the pair of wheels, presumably as the Militaire rider glides to a halt. There’s an elaborate suspension system so the wheels can handle a bump or two. Then, when the light goes green or the stagecoach gets out of the way or whatever, the rider eases out on the clutch, the Militaire moves forward and the second pedal is depressed and up come the wheels.

The pedal behind the floorboards on the right, by the way, is the step starter, with linkage and rachets to the engine’s flywheel. All the framework aft of the engine is for the seat, which is cantilevered, like early Vincent or Yamaha monoshocks, except in reverse and to isolate the rider from the road, rather than the machine.

The wheels-umm, better make that the big wheels and not the little parking wheels-have wooden spokes. By 1915, metal spokes were clearly superior, but Sinclair liked the old style better. Not only that, wooden-spoked wheels were known as artillery wheels or military wheels and that’s where the machine’s name came from. It’s a guess, but the name and the wheels align with the notion of grace and elegance that Sinclair meant his machine to have.

Expanding on that, the official nameplate tells us this machine is a Militaire-Car, adding that the example here is Car No. 203, and Engine No. 203. The manufacturer is listed as Militaire Motor Vehicle Company of America, Inc., Buffalo, New Y ork. All of which has later bearing, but for now, to look at the machine is to grudgingly agree that if one can make a motorcar that mns on two wheels, that’s what the Militaire is.

It is evident the engineers who designed this machine had a free hand. No bean-counter or marketing man would or could have come up with anything nearly as elaborate as the front suspension or the cantilevered seat.

Just as important, this project was done without stint.

It’s true that there have been several hundred brands listed on the motorcycle market, most of them dating back to the pioneer days. But what the record doesn’t show is that all but a handful of those brands were more like mom-and-pop operations, or a couple of pals who built a frame or two and bought engines, wheels, brakes and so forth from outside suppliers. The Militaire, though, has its own engine and gearbox, very much so. Likewise for the frame, the body parts and on down the line, and we haven’t even considered the differential and what has to be the world’s stoutest speedometer drive.

Exceptions? Sure. The headlight comes from what has to have been an outside source. It’s got “Old Sol” written on the headlight shell, a neat tum-of-the-century play on words. Oh, the hom is tucked inside the headlight shell. Why? Why not? Warm and dry and all that.

And the magneto is Bosch. Another obscure fact here. Historian Griff Borgeson, who knows as much about this era as it’s possible to know, writes that America was pretty much a developing country before the Great War, and was dependent on Europe for expertise in metallurgy and casting and forging. It was easier-and gave prestige-to import Krupp steel than leam how to do as good at home. Even so, the Militaire was designed and produced as a complete machine. There was a plant and a sales staff and an ad campaign, and according to the records, the Militaire-Car was in business from 1911 through 1917, at Indianapolis, Indiana, Cleveland, Ohio, and Buffalo, New York.

Remember get organized the part and about Sinclair persuasion? would raise Militiare money, would but there would be some difficulty and he’d move the company and raise more money-never mind what had hap-

pened to the first investors. Some talker. One has to assume here that he wasn’t a con man, that to a large degree he could persuade other people because he, himself believed in the narrow, two-wheel car.

He did so with some reason. The owner of this example is Richard Morris of Torrance, California. Morris likes to joke that he was at one time the King of Fours. He owned 25 of various early Fours, the Hendersons and Aces, used to ride a Henderson to work, etc. Morris knows his antique Fours.

According to Morris, the Militaire is adequate. There’s plenty of power from the 68-cid engine, considering that the Militaire’s curb weight is 300-plus pounds. The machine takes some getting used to, in that the turning circle matches that of an average-size destroyer, and the one brake was better in 1915 than it is now. Using the right foot to clutch, the right hand on the throttle and the left hand on the gear lever-unless you want to use the right for both, as you were taught to eat dinner in formal company-takes practice.

But, says Morris, once the operator has the drill, and allows for the period, the Militaire isn’t bad. Besides, as it turned out, complexity of operation never came close to being the Militaire’s problem.

What was the problem?

Basic. Nobody wanted a narrow, two-wheeled car.

Sure, the Militaire, as seen here, went into official production in 1915. It made a splash in the papers, ads were taken out and so forth. They sold a handful: It’s safe to guess that the serial number 203 means the Militaire-Car production run began at 200 or maybe 201. But it’s also safe to say that while some people wanted motorcycles and more people than that wanted real cars-cars with their four wheels located one at each comer and with electric start and a top and doors-there were hardly any people who wanted a narrow car with wheels you put down and raised up yourself.

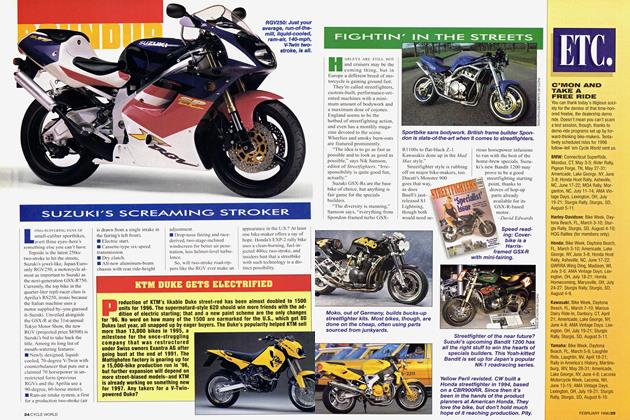

Not that anything as simple as customer rejection could keep our Mr. Sinclair down. From 1917 through 1922, in Jersey City, New Jersey, and then Springfield, Massachusetts, came the Militor. Sinclair had found more backers, and he’d let the engineers loose again.

Most obvious of all, this time the narrow car had 1 ) lost its parking wheels and 2) acquired a sidecar. This was permanent; that is, the Militor-presumably, he had to change the

name when he began the new company-came with a sidecar and only with a sidecar. Thus, no parking wheels; no stands for front or rear wheels; the step-start lever was moved from right to left, where the operator could step on it; and the clutch was now on the left, as had been standardized, with the H-pattern shifter no longer labelled because the pattern had also been made standard.

More important, the skinny frame rails had been replaced with a stamped platform. The engine was stitched into its opening, serving as a more efficient stiffener. The chassis was still horizontal, except the structure for the steering head is stronger and simpler, and the pairs of girders have become...a telescopic fork! There’s still center-hub steering.

The seat is no longer cantilevered. Need not be, because the rear wheel is suspended, with the differential located by a pair of stacked leaf springs. Wheelbase was increased, from 65 inches to 66.

Power is still by inline-Four, longitudinally mounted and 68 cid, but the pocket valves are now fully overhead, so there’s more power to pull the added weight. The carb now sits at the center of the engine, where it should be, and the magneto now comes from Edison. There's a generator instead of a total-loss battery.

The Militor has what we can call bodywork. The fenders are fully valanced, the better to fend off mud and spray. The sidecar has a top and windshield and, look, that panel atop the handlebars and carrying the hom! It can only be called a pre-quarter-fairing, while around back, the panel holds the instruments and hom button. The floorboards have acquired a stylish curve and the wheel spokes are painted, even if they are still wood.

The first plain fact has to be that the design team did good work. The changes are improvements and they make sense. The Militor is a better piece of work. Next, there’s the same lack of stint. When the project went public, with the official voice coming from still another firm, the Sinclair Militor Corp., Bridgeport, Connecticut, the ad showed a row of machines and described them as “Ten cars that spread a new doctrine on design, performance and economy.” Watch for the Militor when it comes to your town, the ad urged, it’ll be a major day.

Of followed course, the the trickle day never of Militaires, came. A and handful after of he'd Militors taken his fifth bankruptcy, Norman Sinclair faded away. The only piece of good luck in the Militaire/Militor episode seems to be the survival of the examples shown. Back when nostalgia wasn’t nearly as good as it is now, the Militaire turned up in New Jersey, the former property of an employee of one of Sinclair’s companies. The Militor was found in Pennsylvania and even less is known about that machine’s history. Both were bought by collectors in South Africa and were kept there until Morris saw the ads and came up with the high-even for 10 years ago-asking price. Morris found this part and re-did that one, and both machines run, although neither is something you’d take to the store.

Closest we can come to a happy ending for this intriguing saga comes with time.

In the Militaire and Militor we have real forward thinking, a willingness to explore and to defy what passed at the time for common sense. If he’d just hung on, or more probably if Norman Sinclair had simply been willing to use his big and understressed engine, his shaft drive and sound engineering, and admit he was making a motorcycle for gentlemen-well, he and not that other chap with imagination and energy and the willingness to march to his own drum, could have been the man who brought us the Gold Wing.