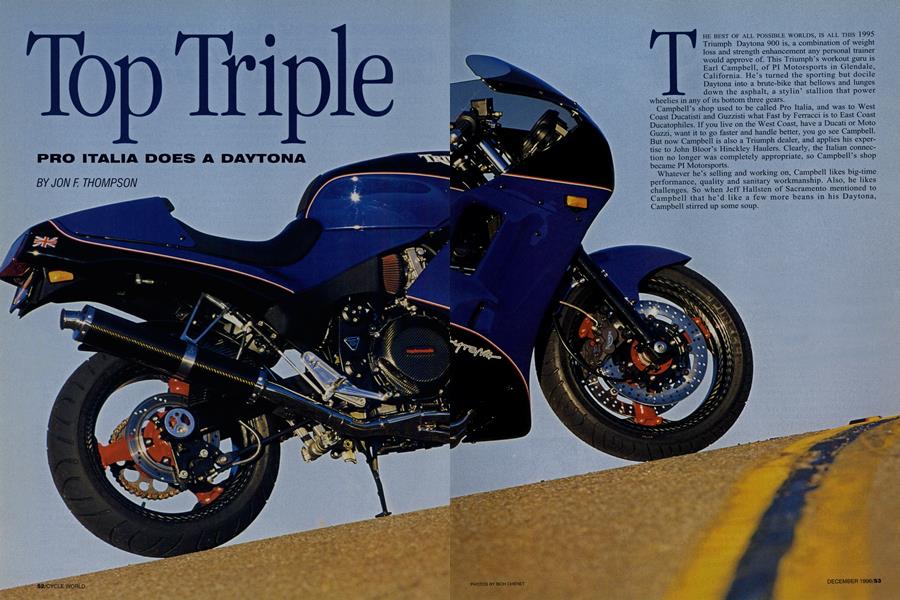

Top Triple

PRO ITALIA DOES A DAYTONA

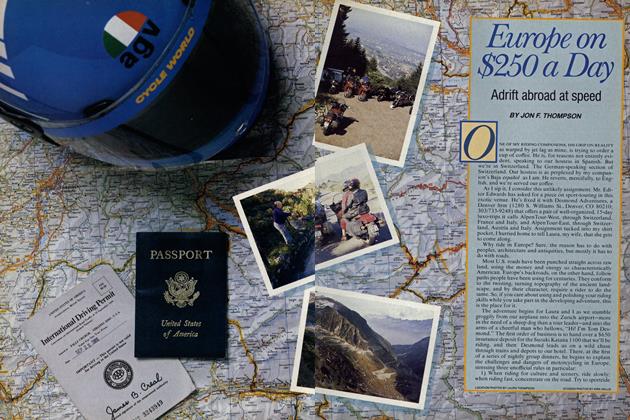

JON F. THOMPSON

THE BEST OF ALL POSSIBLE WORLDS, IS ALL THIS 1995 Triumph Daytona 900 is, a combination of weight loss and strength enhancement any personal trainer would approve of. This Triumph’s workout guru is Earl Campbell, of PI Motorsports in Glendale, California. He’s turned the sporting but docile Daytona into a brute-bike that bellows and lunges down the asphalt, a stylin’ stallion that power wheelies in any of its bottom three gears.

Campbell’s shop used to be called Pro Italia, and was to West Coast Ducatisti and Guzzisti what Fast by Ferracci is to East Coast Ducatophiles. If you live on the West Coast, have a Ducati or Moto Guzzi, want it to go faster and handle better, you go see Campbell. But now Campbell is also a Triumph dealer, and applies his expertise to John Bloor’s Hinckley Haulers. Clearly, the Italian connection no longer was completely appropriate, so Campbell’s shop became PI Motorsports.

Whatever he’s selling and working on, Campbell likes big-time performance, quality and sanitary workmanship. Also, he likes challenges. So when Jeff Hallsten of Sacramento mentioned to Campbell that he’d like a few more beans in his Daytona, Campbell stirred up some soup.

“It just kinda got outta control,” says Hallsten. “I wanted a bike I could ride in the canyons with my Ducati buddies, but that was also smooth enough to sport-tour down to Laguna Seca on. I wanted something you can ride all day.”

Says Campbell, “The Daytona’s a pretty good streetbike as it is, but I think the riding position is too severe, and it could have a better power-to-weight ratio. I mean, the thing is heavy, but that would be okay if it had 20 more horsepower. And it’s not powerful enough, but that would be okay if it was 65 pounds lighter.”

So Campbell set about working from both ends of the problem, pumping the bike up while cutting back its weight.

But first, he looked to apply the comfort levels Hallsten required. He fitted adjustable clip-ons, machined from billet aluminum, that raise the handlebar position by 3 inches. And he fitted billet footpegs and brackets that lower the

pegs an inch and move them forward an inch. This billetfor-stock substitution saved a pound, and

set the tone for the rest of the work Campbell and his chief mechanic, Mike Moran, would do.

They pulled the engine apart and installed a big-bore kit, consisting of pistons and sleeves, from Taylormade, a British supplier of Triumph speed parts. This boosted capacity from 885cc to 985cc, thanks to an increase in cylinder bore from 76mm to 80mm. The trio of pistons supplied with the kit also boosted compression from the stock 9.5:1 to 12:1.

Next, Campbell and Moran made what may be the most interesting and controversial of all their mods. They removed the Triple’s balance shaft, along with the gear that drives it. Triples are unnatural beasts, and their uneven number of pistons vibrate like the Hammers of Hell unless they’re equipped with counterbalancers. But the Daytona 900’s balance shaft weighs 9 pounds. Removing it is like removing 9 pounds from a flywheel, and also figures into

the Triumph’s overall weight reduction.

Next, Campbell hauled the Daytona’s head to C.R. Axtell, who cleaned up the ports to the extent that intake flow was improved by about 20 percent while exhaust flow was improved by 24 percent, all with stock valves.

The standard Daytona cams were retained because, Campbell explains, “We were looking for a midrange monster. I want a bike to just go; I don’t want to be stomping gears all the time.”

Campbell and Moran replaced the stock 36mm Keihin CV carbs with a trio of 39mm Keihin smooth-bores. A visit to the dyno proved the results worth the work, with horsepower boosted to a peak of 119 at 9500 rpm, up from the Stocker’s 97 bhp; and torque increased to 70 foot-pounds, up from the Stocker’s 61.

Engine and ergonomic work complete, Campbell got serious about weight reduction. The wheels, for instance, which retail for a stunning $3490 per pair, are from Taylormade, and use carbon-fiber rims and magnesium centers. They are 27 pounds lighter than the stock pair of wheels, and are so strong, Campbell says, “I’d trust them hitting a rock more than I would a magnesium rim.”

Campbell also added a Taylormade carbon-fiber clutch cover, a carbon-fiber inner fender from a Triumph Super III,

a Staintune exhaust system that removed another 14 pounds, and other carbon-fiber odds and ends that shaved an additional 10 pounds from the Daytona’s weight. Finally, a White Power shock was fitted, and Racetech Gold Valve innards added to the stock fork.

So, how much does the bike weigh now? It tips the Team CW scales at 466 pounds, a reduction of 68 pounds from the 534 pounds our Daytona 900 testbike (CfV, March, 1995) weighed.

With the practical work done, Campbell turned to the pretty. He had the bike’s bodywork painted by Rick Baddon of Huntington Beach, California, in a blue/black color scheme that seems to shrink the Daytona. For further visual reduction, he trimmed the inner fender, and shortened the taillight by % inch. The result, you see here.

We can report that Campbell’s creation meets all, or at least most, of Hallsten’s expectations. The riding position is much improved over that of the stock Daytona 900, the bike looks smaller than the stocker even though it isn’t and it delivers absolutely stunning amounts of acceleration almost everywhere in the rev range.

The downside is just this: That counterbalancer was designed into the Triumph Triple for a reason. Without it, there’s vibration coming at you through the bars, footpegs and tank, enough to put us in mind of the Laverda Triples

Campbell, ever the Italophile, is so fond of. It wasn’t enough to put our fingers and toes to sleep, but we didn’t ride the bike to Laguna Seca, either.

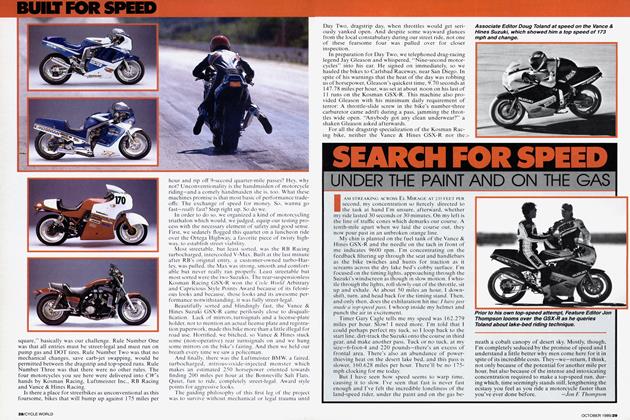

Where we did ride it was over some of our favorite mountain curvery, where the bike demonstrated that a little hot-rodding goes a long way. Start it up, blip the throttle-women and children scatter in fright. And they’d better, or they’ll be sucked down the carburetor intakes. This engine is a beast, picking up revs instantly. It has two

ranges. Between 3500 rpm and 7000 rpm it’s friendlystrong, pulling cleanly, but without urgency. Just right for a nice little sporting cruise. From 7000 rpm on to the 9000rpm redline, though, watch out! Your shoulder and elbow joints get stretched as you hang on, your right wrist gets a workout as it tries to modulate between afterburner acceleration and looping over backward. Rear tires won’t last long.

Fun to ride? You bet. Fun to look at, too. Overall, both Hallsten and Campbell rate the PI Motorsports Top Triple project a huge success.

What’s it all cost, bottom line? Depends what you can get your own Daytona 900 for. To that price, add $9958, which is what Campbell’s work pencils out to.

Is it worth it? Ask Hallsten-if you can catch him.