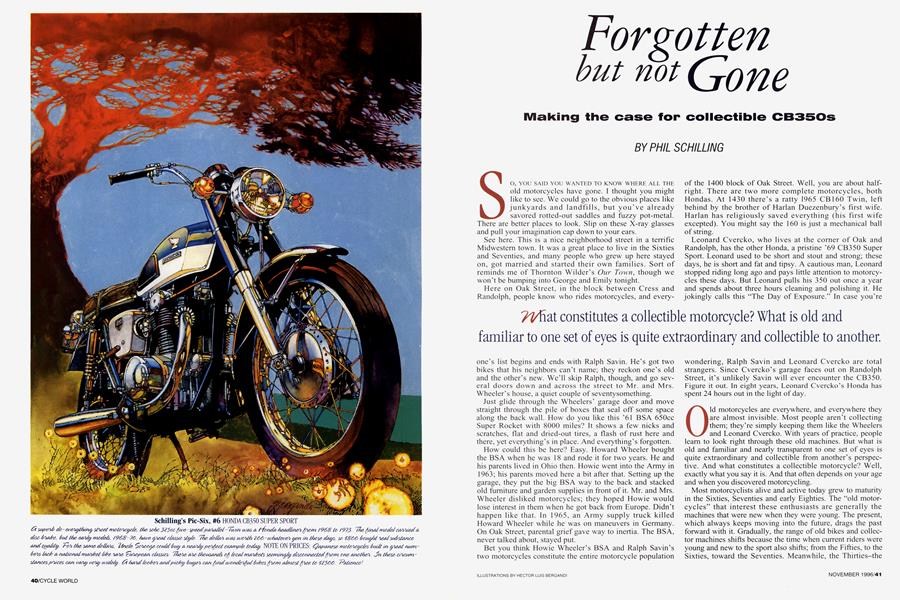

Forgotten but not Gone

Making the case for collectible CB350s

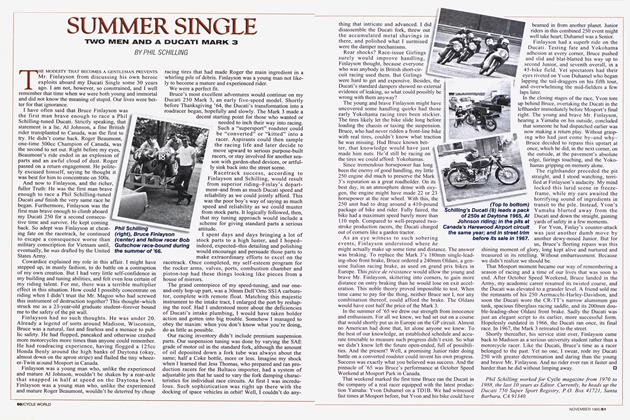

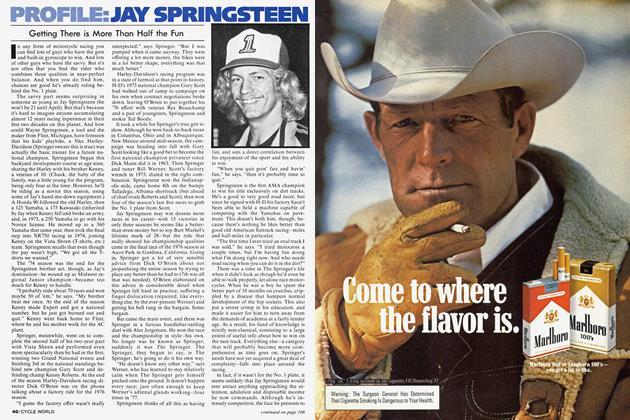

PHIL SCHILLING

SO, YOU SAID YOU WANTED TO KNOW WHERE ALL THE old motorcycles have gone. I thought you might like to see. We could go to the obvious places like junkyards and landfills, but you’ve already savored rotted-out saddles and fuzzy pot-metal. There are better places to look. Slip on these X-ray glasses and pull your imagination cap down to your ears.

See here. This is a nice neighborhood street in a terrific Midwestern town. It was a great place to live in the Sixties and Seventies, and many people who grew up here stayed on, got married and started their own families. Sort of reminds me of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, though we won’t be bumping into George and Emily tonight.

Here on Oak Street, in the block between Cress and Randolph, people know who rides motorcycles, and every-

of the 1400 block of Oak Street. Well, you are about halfright. There are two more complete motorcycles, both Hondas. At 1430 there’s a ratty 1965 CB160 Twin, left behind by the brother of Harlan Duezenbury’s first wife. Harlan has religiously saved everything (his first wife excepted). You might say the 160 is just a mechanical ball of string.

Leonard Cvercko, who lives at the corner of Oak and Randolph, has the other Honda, a pristine ’69 CB350 Super Sport. Leonard used to be short and stout and strong; these days, he is short and fat and tipsy. A cautious man, Leonard stopped riding long ago and pays little attention to motorcycles these days. But Leonard pulls his 350 out once a year and spends about three hours cleaning and polishing it. He jokingly calls this “The Day of Exposure.” In case you’re

Wiat constitutes a collectible motorcycle? What is old and familiar to one set of eyes is quite extraordinary and collectible to another.

one’s list begins and ends with Ralph Savin. He’s got two bikes that his neighbors can’t name; they reckon one’s old and the other’s new. We’ll skip Ralph, though, and go several doors down and across the street to Mr. and Mrs. Wheeler’s house, a quiet couple of seventysomething.

Just glide through the Wheelers’ garage door and move straight through the pile of boxes that seal off some space along the back wall. How do you like this ’61 BSA 650cc Super Rocket with 8000 miles? It shows a few nicks and scratches, flat and dried-out tires, a flash of rust here and there, yet everything’s in place. And everything’s forgotten.

How could this be here? Easy. Howard Wheeler bought the BSA when he was 18 and rode it for two years. He and his parents lived in Ohio then. Howie went into the Army in 1963; his parents moved here a bit after that. Setting up the garage, they put the big BSA way to the back and stacked old furniture and garden supplies in front of it. Mr. and Mrs. Wheeler disliked motorcycles; they hoped Howie would lose interest in them when he got back from Europe. Didn’t happen like that. In 1965, an Army supply truck killed Howard Wheeler while he was on maneuvers in Germany. On Oak Street, parental grief gave way to inertia. The BSA, never talked about, stayed put.

Bet you think Howie Wheeler’s BSA and Ralph Savin’s two motorcycles constitute the entire motorcycle population

wondering, Ralph Savin and Leonard Cvercko are total strangers. Since Cvercko’s garage faces out on Randolph Street, it’s unlikely Savin will ever encounter the CB350. Figure it out. In eight years, Leonard Cvercko’s Honda has spent 24 hours out in the light of day.

Old motorcycles are everywhere, and everywhere they are almost invisible. Most people aren’t collecting them; they’re simply keeping them like the Wheelers and Leonard Cvercko. With years of practice, people learn to look right through these old machines. But what is old and familiar and nearly transparent to one set of eyes is quite extraordinary and collectible from another’s perspective. And what constitutes a collectible motorcycle? Well, exactly what you say it is. And that often depends on your age and when you discovered motorcycling.

Most motorcyclists alive and active today grew to maturity in the Sixties, Seventies and early Eighties. The “old motorcycles” that interest these enthusiasts are generally the machines that were new when they were young. The present, which always keeps moving into the future, drags the past forward with it. Gradually, the range of old bikes and collector machines shifts because the time when current riders were young and new to the sport also shifts; from the Fifties, to the Sixties, toward the Seventies. Meanwhile, the Thirties-the people and machines-fade into dusk.

Schilling’s Pic-Six, #5 KAWASAKI 903 Z-1

¿ate in /971. Tftawasadi launclted tire 903ce Z/ ftts marvelous twin -cam enp/nc. operating en 7relt, pave the Tftawasadi tire civdity oft a hienda C3750 Sut tummp up the tach needle summoned a fterociousness that was pure Z-/ Sot as ftinely polislted as the C&730, tire 903 was the ftorttftied expression oft the same concept ¿you could cad tire Z/ a tot oft thinps. torinpisn t one oft them

Just a few years one way or another can make a huge difference. Moto Parilia, a force in the United States in the late Fifties and early Sixties, died shortly thereafter. If you discovered motorcycling in 1962, then you might remember these

Italian lightweights. Had your doorway to motorcycling opened a few years later, in 1965, you might well draw a complete blank on Parilia. And Moto Rumi, Mondial, Zundapp and Horex.

Motorcycle enthusiasts are new to the sport only once. Generally, they enter motorcycling with an initial burst of incredible energy and enthusiasm, and this primary period includes a great number of powerful, enduring experiences. Everything is new, important, fresh and exciting. There’s a drive to know all, try all.

Sometimes newcomers actually manage to organize their entire lives around motorcycling for two or three years-before serious employment or other abiding commitments of adult life take precedence. Over time, an individual’s knowledge of motorcycling and machinery may significantly broaden and deepen as he develops a studied and sophisticated approach to the sport. But for the typical enthusiast, the most powerful emotional experiences in motorcycling are normally embedded in the initial entry-and-immersion period.

When enthusiasts begin to collect motorcycles, they tend to revisit those special times when raging enthusiasm first con-

Collection operates on scarcity; far more Hondas survive today than can be absorbed by collectors. In a world of perfect justice, 305 Super Hawks

would be gold-chip bikes.

Schilling’s Pic-Six, #4 HONDA CB750K The CS750 7ft introduced in /969. is tide ftpcotlo //. ftt divided history into ¿öftere and aftter. hirst modem mass-producedftour-cylinder, t-lrstproduction streettide with a hydraute dise trade fthatte'uny pe rfto renonce Ttntetievatte smoothness and civility, ftarty tides had aftierceness later versions tost, andtheftirst 7ft-tides, /969-70-77, were tire most handsome.

sumed their lives. Perhaps this happens because they can recall their first motorcycle universe with greater clarity and detail and relish than their motorcycle world of the 1990s. Expanding interests can soon have collectors exploring and gathering beyond their initial base, but as a rule, few totally abandon that first ground.

Demographics also explain much about motorcycle collection: why there are so many motorcyclists today, 35 to 50 years of age; why “old motorcycles” are everywhere if you know where and how to look; and why Japanese machines appear increasingly popular as collectible bikes.

Motorcycling began surging in the Sixties. The leading edge of male baby boomers embraced motorcycles, and the sheer numbers of subsequent boomers in large part accounted for the astounding growth in motorcycle sales. Indeed, the last 35 years of motorcycling in the United States has been a product of the Sixties generation-if you understand that much of the Sixties actually happened in the Seventies. That generation carried motorcycling to spectacular sales peaks about 15 years ago when Americans bought about one million new motorcycles every year. That’s five times the size of current new-bike sales. Though big now, motorcycling was gigantic then.

Japanese manufacturers dominated the market. Honda was the largest and most prolific manufacturer in the world in 1959, producing about a half-million machines. In the United States, however, Honda began modestly, selling 1700 motorcycles when entire U.S. sales were about 60,000 units.

Within four years, imports exceeded 150,000, and by 1964, Honda’s share of the market approached two-thirds. For a long period, Honda alone sold far more new motorcycles annually in the United States than all manufacturers combined sell here today. In 1984, American Honda sold 776,000 new motorcycles, scooters and AT Vs.

These impressive numbers suggest the dilemma in collecting Japanese motorcycles, especially Hondas. Although the vast majority of American enthusiasts warmly remember their baptism into motorcycling, which likely took place on a Honda motorcycle, far more Hondas survive today than can be absorbed by those now collecting them. Collection operates on scarcity. That process penalizes brilliant motorcycles that major manufacturers turned out by the tens-of-thousands.

Obviously, many people who collect Japanese machines concentrate on the significant, exotic and rare. For example, beyond the factory racing motorcycles, the crown jewels of Honda are the limited-production racers of the early Sixties: the CR110 50cc Single, CR93 125cc Twin, CR72/77 250/305cc Twins. The 1959-62 CB92 Benly Super Sport 125 and CB92R Benly SS Racer, though common by comparison, are still longtime favorites. Limited-production racebikes, such as Yamaha’s outstanding TD\TR\TZ series, have strong followings, and Superbike boosters tout machines like Eddie Lawson Replica Kawasakis. This list could be stretched out considerably, and in every case scarcity makes such bikes expensive.

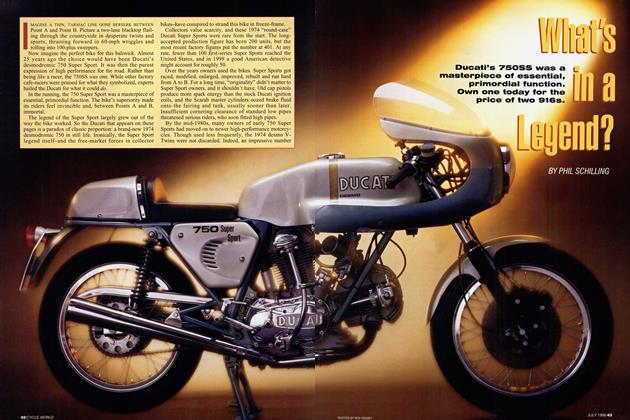

Being rare may make a collector vehicle costly. Being significant is something else; that has little to do with the production numbers-high or low-of a given model. However, significant products that have been mass-produced in enormous numbers do suffer in market value: Too much of a good thing is a bad thing. Honda’s first CB750 four-cylinder was an engineering, production and marketplace landmark; its significance in motorcycling is monumental. Placed next to the Honda, Ducati’s 1974 750 Super Sport Desmo pales in the cosmic scheme of things. But after the CB750’s introduction in 1969, American Honda sold more than 400,000 units in a 10-year run. The Italians sent about half the 200-unit production of Ducati 750 Super Sports to the United States. Scarcity rules. The 750SS Desmo is rare and worth a lot; the CB750 is plentiful and worth a lot less.

In a world of perfect justice, Honda CB72 250cc Hawks (1961-1966) and CB77 305cc Super Hawks (1961-68) would be gold-chip collector bikes. But these intense little parallelTwins again illustrate the tyranny of numbers. Several years ago, bike collectors noticed precious few CB72/77s around. Had these bikes fallen out of view or had attrition made them genuinely scarce? Then a trickle of CB72/77s appeared; some beautifully restored and well-kept originals fetched up to $5000. The scent of money produced predictable results. Hardto-find spare parts-shock covers, tach/speedo heads, front fenders, muffiers-got pricier. Nevertheless, some people pressed forward with restorations, concluding the bikes were now “worth it.” Before long, the trickle of CB72/77s gushed into a torrent, and prices promptly sank. Abundance was the enemy.

Numbers, supply, demand, value: These words are part of the conventional language of collecting. We employ these words, and the economic concepts associated with them, routinely without giving much thought to the unstated assumptions that lie behind the language. The first and basic assumption holds that collectible vehicles will always appreciate in real value over time. This leads to the next idea-that is, collectible vehicles can be, or ought to be, commodities bought and sold for profit in a marketplace. A third, and equally shaky, idea is that these collectible vehicles can be, or ought to be, “good investments,” with the same status as traditional elements in an investment portfolio.

Schilling’s Pic-Six, #3 KAWASAKI HI 500

Tdo ycu/i fiuends love to tedyou dud ¿^apanesc motodycles a/ie appliances duU loch duuiacten? 7>ut them on a /969 ld/ 5öó two-stnohe Tutiplé. The chaiiocten enewdwon i believe how iowdt? and ‘lawbencd dus Sawasahi b'iawlc'i is. id/ fiaient wheels would be stamped oui-mail Sub ~/3~ seeendouante'i-miles one intense tdanddni^ is Sixties-shahÿ. Tlotsy hnccmfiodabtc dhanae/ei'

For the overwhelming majority of collectors, these assumptions are nonsense. These notions gained credibility in the 1980s when collector automobiles went from a labor of love and loss, to a break-even proposition, and finally to a highprofit enterprise during the speculative bubble of 1987-89. When the bubble burst, the value of collector cars plunged dramatically, and those automobiles went right back to a labor of love and loss. Nonetheless, the remembrance of the bubble and the promise of easy money lingers like bad perfume. In the realm of collector motorcycles, the honest formula is money-for-satisfaction rather than money-for-profit.

Schilling’s Pic-Six, #2 YAMAHA DT-l 250 ENDURO

dn the midSixties, manufiaetuicis devised die stneet-scnamblei, a hind ofi ofififiead bihe that 'icady wasn t lyamaha had a, betted idea, dn /968, it buid a dufifiei s ofifi - ioad dStdT~bihe and civilised it fioi highway use The TdT/ cue -ated the massappealenduic catexjoiÿ in the It S hew collectons 'iceccjni^c die TdT-/ s impoitanee in ¿Tmcnican mctcncyclin^ Sc the fiiist on yeuti bloch

Schilling’s Pic-Six, #1 HONDA CB77 305 SUPER HAWK toÿedhen coetti the ¿66ce CS?2 hfiaco/o, t/ie ‘vupeï hfieuok com ttie ficMt tm/y modem meteïeycte most tsimeieeevis eneecmteied pushbutton stetdin^. >iet/¿d>te c/cct’itcs. fimitmttc b\¿d?es. /66 -plus-mphpenfievrnvice, monedeóte sehe sephtsttoedeen mide/npiesuee smeottmess 77ie piepel td¿iwh com ¿vi ¿dsetute tevehdten in /96/ Thedf -five yeans t¿de\ d s stdt¿vi eye-epeeie'i

Follow your heart and be sure the head you’re using is your own. Your friends might fancy Sixties Triumphs or Harleys, and they may ridicule your wanting a 1968 CB350 Super Sport:

At $800, a CB350 was an inexpensive, high-tech, high-quality masterpiece.

Thousands still exist. Running examples range from ratty to scruffy to showroom perfect. For most people, a CB350 is not a restoration subject. As a serious restoration project, a Honda 350 could demand the same time and effort required by a very rare machine. On the other hand, CB350s belong to a broad category of models which, if they break, can often be replaced for less than they can be repaired. This makes a very good CB350 an excellent candidate for “renovation.” Renovation involves replacing damaged or worn parts found on one example with original unscathed, unworn parts from a donor bike of the same series.

Like restoration, a worthwhile renovation project requires the best possible example you can find. Be picky and be patient. Above all, guard against scooping up six rotters from which one rat might arise. There are ways to pinpoint a wonderful example. Research the location of Honda dealers, circa 1968 to 1975, and place classified want-ads in local newspapers. Small-town papers sometimes work well because a comparatively stable population has had the inclination and

Jh the realm of collector motorcycles, the honest formula is money-for-satisfaction rather than money-for-profit.

“Parts are everywhere for Triumphs.”

“How would you ever duplicate that clear-coat stuff Honda put on cases?”

“A CB350 won’t ever be worth anything; you won’t get your money out of it.”

Heed your own instincts and sensibilities. You can legitimately believe that collector vehicles normally absorb money rather than make it. You may demand a collector bike that’s easy to use rather than too precious to exercise. You might want a motorcycle that has an important place in American motorcycling. Was the CB350 such a thing? Soichiro Honda thought so, and you can understand why.

Measured by sales numbers or performance figures, Honda’s CB350 was sensational. From 1968 to 1974, American Honda sold almost a half-million of these 325cc sohe Twins in CB350 roadster (274,000 units) and CL350 street-scrambler (218,000 units) trim. In 1972, American enthusiasts bought 70,000 CB350s and 45,000 CL350s. These Hondas were wildly successful because they were, dollar for dollar, tremendous motorcycles. CB350s were tough, smooth, reliable, taut and stable. They made good box-stock production racebikes, could withstand savage beatings, would drone around town and campus without temperament, or could run cross-country effortlessly on the shortest of invitations.

space to save things. “Wanted: Honda CB350 Twins, late ’60s/early ’70s. Phone...” Such ads can lead to remarkable bikes. They will also uncover a lot of awful motorcycles and some other amazing things that people thought were Honda 350s, or at least close enough that they figured you might be interested.

The reward for finding a near-perfect motorcycle is great savings of time and grief and money. The better the bike, the fewer parts need replacing. When done carefully, swapping parts produces an original, unrestored, unmolested showroom-stocker. “Renovation to original” only works because American Honda sold these 350s in massive numbers. At last abundance becomes an ally.

Originality, you may decide, is a silly concept for your CB350. Stock shocks and period tires belong anywhere but on the motorcycle. And how many exactly original CB350s does the world need? The bike’s real value lies in how well it works, its solid and unburstable feel, its mellow wail at 10,000 rpm, its surprising swiftness out on the road.

Admit it: You’re pleased to remind your friends with early Triumphs how complete and civil this sporty Honda is. It’s an ego trip to ride a motorcycle, so ubiquitous once and seemingly singular now. Whatever their age or origin, truly remarkable motorcycles issue their own invitations to high adventure and good fellowship. And in this respect, old motorcycles remain forever new.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue