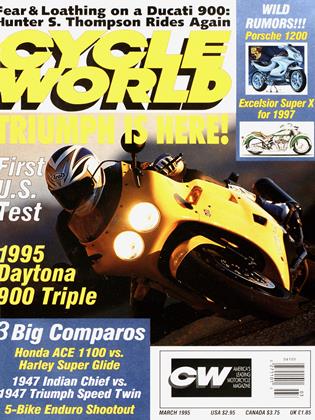

CYCLE WORLD TEST

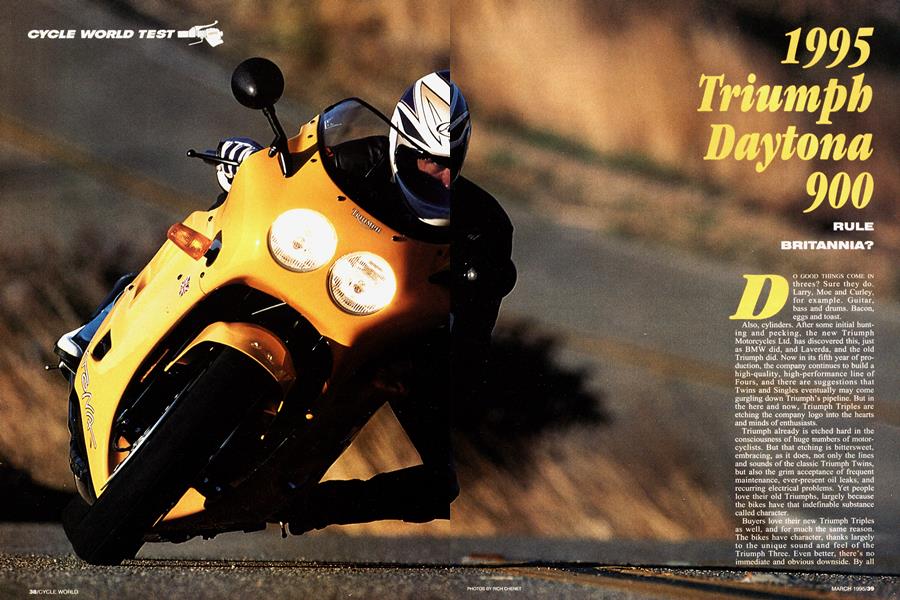

1995 Triumph Daytona 900

RULE BRITANNIA?

DO GOOD THINGS COME IN threes? Sure they do. Larry, Moe and Curley, for example. Guitar, bass and drums. Bacon, eggs and toast.

Also, cylinders. After some initial hunting and pecking, the new Triumph Motorcycles Ltd. has discovered this, just as BMW did, and Laverda, and the old Triumph did. Now in its fifth year of production, the company continues to build a high-quality, high-performance line of Fours, and there are suggestions that Twins and Singles eventually may come gurgling down Triumph’s pipeline. But in the here and now, Triumph Triples are etching the company logo into the hearts and minds of enthusiasts.

Triumph already is etched hard in the consciousness of huge numbers of motorcyclists. But that etching is bittersweet, embracing, as it does, not only the lines and sounds of the classic Triumph Twins, but also the grim acceptance of frequent maintenance, ever-present oil leaks, and recurring electrical problems. Yet people love their old Triumphs, largely because the bikes have that indefinable substance called character.

Buyers love their new Triumph Triples as well, and for much the same reason. The bikes have character, thanks largely to the unique sound and feel of the Triumph Three. Even better, there’s no immediate and obvious downside. By all reports, the bikes don't leak electricity, their gaskets and crankcases don't drool oil, and maintenance schedules are on par with those of other modern motorcycles.

As surprising as the concept sounds, an inline-Triple-the engine which powers Triumph’s most popular bikes—makes a good deal of sense. It can be more compact than a Four, with power delivery that is surprisingly smooth, given its oddball engine dynamics.

Those dynamics are the result of the Triple's uneven number of cylinders, and because Triples fire oddly-combustion occurs every 240 degrees since the crankpins are spaced around the crankshaft ai 120-degree intervals. The three-cylinder configuration produces not only the design's characteristic raspy exhaust note-doesn’t sound like a Twin, but doesn’t sound like a Four, either-it also causes the crankshaft to oscillate the way a kayak paddle does, each end of the crank trying to describe a circle while the center remains still Unchecked, the result ing vibrations are sufficient to jiggle the amalgam right out of your dental work.

But Triumph, like BMW, with its K75 Triples, has tamed the Triple’s vibes by use of a balance shaft that reduces the 885cc dohc engine's quaking to levels well below those felt in some current inline-Fours.

These new Triumphs are long and tall, even taller than they might otherwise be, because instead of a compact twin-spar design, they use a backbone frame. This incorporates a large tubular spine that runs aft from the steering head over the top of the engine and then down to the swingarm-pickup point. The wheelbase is stretched to 58.7 inches. By comparison, the wheelbase of a Honda CBR900RR is 55.1 inches. Now, 3.6 inches may not sound like much, but when you're talking motorcycle wheelbases, it’s a bunch.

It's fortunate, then, that the Daytona relics upon elegant proportions. Because its shape and components are very cleverly drawn, the Daytona doesn’t look like a big bike, not until you get right up close to it. Then, you notice not only its size, but the attention to detail Triumph’s designers have lavished upon it. Paint is rich and thick, with no orange-peel. The bodywork is of very high quality, and it all fits together as if it was designed and built in Japan.

Triumph has been very forthright about its use of outsourced equipment. That outsourcing is immediately evident in the handlebar switchgear and the clutch and front-brake levers, all of which look like they were snatched straight from Kawasaki’s parts bins, while the front brake calipers, minus their Triumph script, might have come from a GSXR750 of a few years back. Other details, however, bear Triumph's own touches-the white-faced, black-figured instruments, for instance, and the cast-alloy brake and shift pedals have a very high-end, European look. Triumph built, or custom-specified, parts when it had to, and didn’t when an off-the-shelf item would do. No need to reinvent the motorcycle,

after all. Better to concentrate on refining a contemporary, if conservative, design, something Triumph has done very well.

The design is conservative by several yardsticks. To satisfy the financial yardstick, the design is modular, so that pistons, rods, cams, valves, frames, wheels, brakes, suspension components, seats, instruments and various other bits are shared by most Triumph models, as are the tools and jigs the bikes are machined and built upon. To satisfy the reliability yardstick, the bike’s engine and transmission are particularly robust, so much so that the engine is considerably larger than it might otherwise have to be. And to satisfy the yardstick representing the rider the bike is mostly aimed at, steering geometry is 27 degrees of rake with 4.1 inches of trail-quite conservative, by contemporary standards. The fork is a conventional unit that offers compression, rebound and preload adjustments, while the shock offers just rebound and preload adjustments. One interesting note-shockpreload adjust is hydraulic, donc via a knob located under the seat.

Back to the engine: It’s a very appealing piece, in spite of the fact that its considerable height and length, with very little forward cant, requires that the motorcycle it powers also be tall and long. Hop aboard, thumb the starter. It fires right up from cold with just a little choke, providing evidence that it isn’t jetted too lean in the interest of meeting emissions standards. Pull the clutch in, click the trans into gear, and get rolling. You’ll find some really important things going on here. First, clutch actuation is amazingly smooth and controllable, thanks to nine friction plates and seven steel plates, all of them a fat six inches in diameter. This, friends, is the way clutches are supposed to work. This also is the way transmissions are supposed to shift. The Triumph's six-speed box clicks between ratios with the short-throw, precision certainty of a rifle bolt. No missed shifts here.

And if you just forget to shift, or neglect to, the Triumph has you covered, thanks to a deep, rich spread of torque. The engine pulls like a team of oxen from right off idle, but comes into its power zone at about 5000 rpm, where it’s making 55 rearwheel horsepower, and pulls hard to its 9500-rpm redline, where horsepower production is up to 97. Go beyond that-there’s really little need to-and you bump emphatically into the electronic rev limiter. So you stay in the fun zone, that area between 5000 rpm and 9500 rpm, where you're rewarded with sharp, quick throttle response, hard-hitting acceleration, a glorious baritone exhaust yowl and the delicious mechanical whir of valve gear and other engine components.

What you find, underway and under the spell of the Triumph's captivating engine—which is sufficiently smooth that the bike's mirrors really mirror what’s behind you-is that the bike’s proportions dictate your riding style. Because of its length and steering geometry, it likes long, sweeping corners, and is rock-solid in a straight line. It's tall, with a considerable portion of its weight up high, so it doesn’t like to be flicked quickly from side to side. You handle it in classic fashion, gently urging it to change directions and flowing through corners in a succession of graceful arcs instead of suddenly hammering the bike into a lean the way you might a harder-core sportbike. Bending the bike into a curve requires moderate pressure on the handlebars, but once leaned over, the steering is nicely neutral, though the fork will give a bit of a waggle when the bike is leaned over in mediumspeed corners. Diddling with suspension adjustments didn't entirely rid Cycle World's testbike of this trait.

What you find while you're twisting suspension-adjustment controls is that the Daytona’s suspension values comprise the one area Triumph might need to rethink. Fork rebound damping is overly firm, while shock rebound damping is too soft, even on its hardest setting. You have to be thoughtful about your shock-preload setting, because if you firm up the preload, rebound also is quickened, with no way at all to slow it back down. Not good. Some juggling of fork oil, and a bit of shock revalving, would cure these ills.

One other oddity that comes to light aboard the Triumph is the very long reach from seat to handlebar, and the relatively short span from seat to peg. Also, with the balls of your feet on the pegs, bulges in the bike’s lower sidepanels splay the your heels out. This is uncomfortable, but the rider learns to make allowance.

That's about the only allowance. With just a few exceptions, the Triumph Daytona 900 is a complete and competent piece of equipment. Among the interesting things it does is illustrate the seeming national characteristics streetbikes have developed. Japanese motorcycles comprise a large two-wheeled category, and most enthusiasts know and appreciate their common traits. BMW builds something different, a second category with its own special character and personality. Ducati builds a third category, Harley-Davidson a fourth, and now Triumph is offering an additional category. So what we seem to have is a wide variety of appealing national motorcycle types, each with its own special flavor. In Triumph’s case, the appeal is there even if the technology behind the bikes isn't exactly pushing the edges of the envelope. But is that so bad? Harley has shown that it isn’t. Triumph has polished fundamentally mature design and technology, breaking no new ground, to produce a very appealing motorcycle with its own special character. It's character that will likely be sufficiently attractive to sell every one of the 2000 bikes the company plans to bring to the U.S. this year, enough to make Triumph, once again, a motorcycling presence here.

Think of it as a British conquest, with the conquering power wielding terrific motorcycles.

TRIUMPH DAYTONA

$10,995

EDITORS NOTES

AN HOUR IN THE SADDLE OF THE Triumph 900 Daytona and my aching upper body feels as though I’ve just completed the grueling 200-miler by The Beach. Quite frankly, the Daytona’s long reach and low bars seem out of touch with the bike’s realworld performance envelope. Heck, I can think of at least three 600cc sportbikes with more accommodating ergonomics that also easily outgun the 900 in speed, handling and price.

In all fairness, the Daytona’s three-hole mill does deliver a wonderfully wide spread of power through a precisely shifting gearbox. The throaty growl of its twin exhausts, which sounds more like an Italian Twin than a Japanese Four, is music to the ears. And there’s no way on Earth the sight of its radiant-yellow paint wouldn’t brighten one’s day.

As for riding the Triumph down to Florida for Bike Week in March? 1 think I’d be inclined to trailer it to the Georgia state line. -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

TRIUMPH’S DAYTONA 900 OFFERS FURther proof that these are exciting times for U.S. motorcycle enthusiasts, particularly if you’re looking for a sportbike that’s not made in Japan.

Personally, I find the Daytona's styling a bit dated, although its fit and finish-from the near-flawless paint to the raised Union Jack badges-is spectacular. I’m also impressed with the bike’s engine. Throttle response is marvelous, and the 885cc engine will pull from 1500 rpm in fifth gear. Unfortunately, engine heat is ducted directly onto the rider’s shins; I wouldn’t suggest this bike for summer desert crossings. Also, the ergonomics are more aggressive than the bike’s performance would suggest. This is no CBR900RR killer-the Triumph’s weight, steering geometry and wheelbase assure that.

As I see it, the Daytona 900 is a splendid 80th-percentile sportbike. Just leave the all-out comer carving to the real repli-racers. -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

A LITTLE PERSPECTIVE HERE, AND SOME hopes. This new Triumph has a lot going for it. Build-quality is high. Graphic treatment is exciting without resorting to the now-tired nuclear-zebrastripe motif. It sounds great, looks right and has the best motorcycle name ever devised stenciled across its fuel tank. This is one sportbike that stands out from the crowd. All good stuft'.

But. At $ 11,000, the Daytona is not cheap. Nor, for that kind of bread, do you get anywhere near class-leading performance. Enthusiasm aside, the Daytona is about a half-step behind state-of-tlie-sportbike-art. Then there’s the Daytona's mission profile-does America really want an ergonomically uncompromising, 534-pound neo-cafe-racer?

Bottom line? The Daytona 900 and the rest of line are a very well-placed first step for Triumph America. The bikes will sell, but if the company plans to live off its name and past glories, there could be trouble. What’s that quote about those who forget history being condemned to repeat it....

-David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings

March 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcycling For the Duration

March 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCNo Sharp Corners

March 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupPorsche Building A Bike?

March 1995 By Robert Hough -

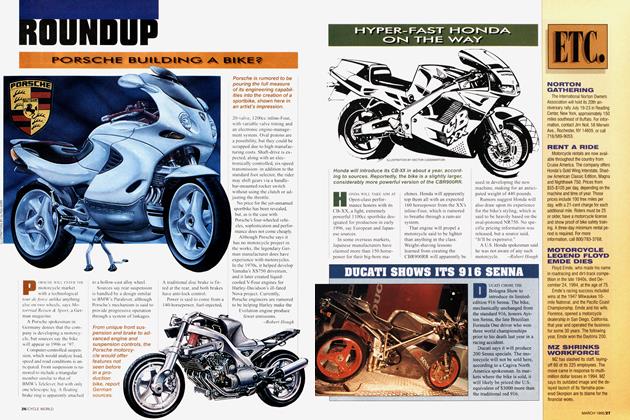

Roundup

RoundupHyper-Fast Honda On the Way

March 1995 By Robert Hough