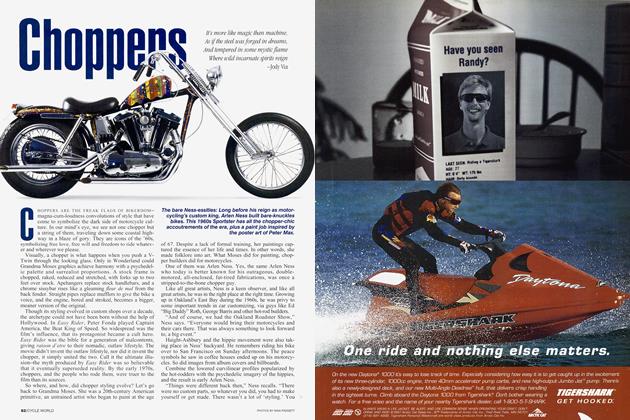

THRILLS! SPILLS!

THE STUNT Men & Women WHO DO THE MOTORCYCLE SCENES ACTORS DON'T DARE

NINA PADGETT

IT TAKES MORE THAN GREAT ACTING TO BRING magic to the big and small screens. Movies and television shows-especially ones that feature motorcycles-are about action.

And behind every chase and explosion is a man or woman you probably wouldn't recognize on the street. They are the riders who make these scenes happen, the stunt-doubles who step in when the going gets rough.

Although they have played a big role in the entertainment industry since the silent film era, theirs is becoming a lost art. As the profession grows more technical, special-effects engineers and computers do an increasing amount of modern stunt sequences. But the following stunt professionals are the real deal. Their combination of timing, reflexes, athletic ability and iron will have brought us some of the greatest motorcycle ` scenes ever put on film.

BUD EKINS

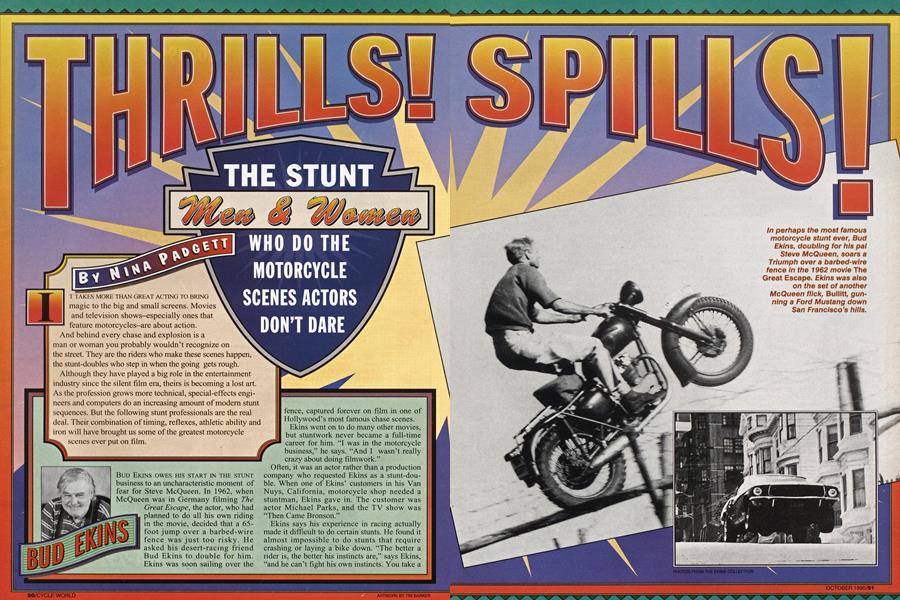

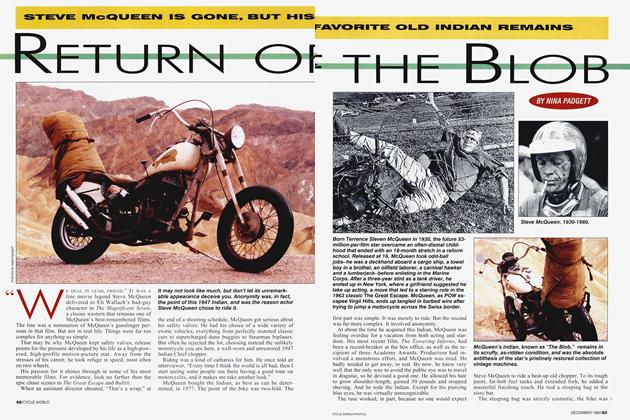

BUD EKINS OWES HIS START IN THE STUNT business to an uncharacteristic moment of fear for Steve McQueen. In 1962, when McQueen was in Germany filming The Great Escape, the actor, who had planned to do all his own riding S~, in the movie, decided that a 65foot jump over a barbed-wire fence was just too risky. He asked his desert-racing friend Bud Ekins to double for him. Ekins was soon sailing over the fence, captured forever on film in one of Hollywood's most famous chase scenes. Ekins went on to do many other movies, but stuntwork never became a full-time career for him. "I was in the motorcycle business," he says. "And I wasn't really crazy about doing filmwork."

Often, it was an actor rather than a production company who requested Ekins as a stunt-dou ble. When one of Ekins' customers in his Van Nuys, California, motorcycle shop needed a stuntman, Ekins gave in. The customer was actor Michael Parks, and the TV show was "Then Came Bronson."

Ekins says his experience in racing actually made it difficult to do certain stunts. He found it almost impossible to do stunts that require crashing or laying a bike down. "The better a rider is, the better his instincts are," says Ekins, "and he can't fight his own instincts. You take a motorcycle rider who’s used to instincts saving his life all the time and tell him, ‘You run down there at 60 mph and jam the brake down ’til you’re going sideways.’ Well, when he gets on that brake, he’ll automatically correct it and straighten himself out,” he says.

“Actually, 1 was scared a lot of times, afraid I was gonna get hurt,” Ekins admits. That didn’t stop him, though. “Sometimes, if you’ve got something really tough to do, you don’t sleep the night before. But you do it.”

RONNIE RONDELL

HOLLYWOOD’S MOVIE SETS WERE Ronnie Rondell’s playground. He grew up on the backlots when his father directed movies after World War II. Rondell planned on following in his father’s footsteps, but motorcycle racing, then stunt riding, intervened.

His racing experience paid off when the director yelled, "Action!" on the set. "It's the riding experience that gives you the control to do what you've got to do in stuntwork," Rondell asserts. I_.. L...--, ..-, ...t.~,.... i,...

In those days when the stunt required special equip ment, it was up to the stuntman to figure out what was needed and work with the special effe.cts experts to build it. "Stuntwork has gotten real technical. They want it bigger and better every time you do a movie. We've been fortunate to keep up by stealing equipment and ideas from all the sports. Our pads come from foot ball, and all the riding vests and flack jackets come from motorcycles," Rondell explains. `And now the effects departments use new equipment which enables you to do a fall on a real thin cable and literally drop for 1000 feet."

Occasionally, a stunt backfires, and Rondell knows the consequences of that all too well. One of his sons was killed on a set. Nonetheless, he feels that there is an unprecedented emphasis on safety in the business. “Before, when you put up a complaint about safety, you'd be poohpoohed or overridden. Today, the stunt coordinator has the power to stop filming if he thinks the situation is unsafe,” Rondell says.

Rondell is now in his fourth decade of active stuntwork, with no plans to retire. The attraction, he says, is clear to anyone who races: “It’s the thrill, the adrenaline rush. It’s the same thing as sitting on the starting line, watching for that flag, droppin’ the clutch. You’re in it for all you’re worth.”

CAREY LOFTIN

CAREY LOFTIN IS A BORN DAREdevil-which makes him a perfect stuntman. The more dangerous the job, the more he likes it. “I love a challenge,” he says.

“During the course of my career, I’ve done a lot of things that hadn’t been done before. I get a kick out of that.”

Like many stuntmen,

Loftin entered the profession through circus work. It wasn’t long before he was in Hollywood (where he worked with, among many others, W.C. Fields). There was no shortage of work for the skilled motorcyclist, but Loftin soon tired of doing the same “gags” again and again.

“During the War, I was always doing Germans that get blown up going over land mines,” he remembers. He started introducing his own ideas to make the stunts more spectacular. “I’d cut the steering stops off the bike so I could turn the handlebars 90 degrees, then tighten up the front brake so it would barely move,” Loftin describes. “I’d turn the wheel and lock the front, so that the bike would throw me.” That technique was spotlighted in countless movies, including a race sequence in the 1950 picture The Pace of Thrills.

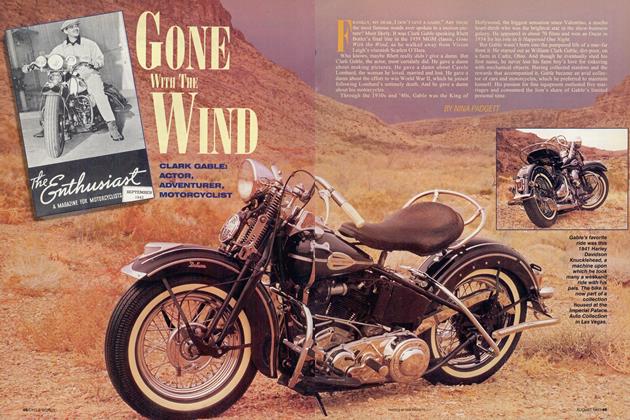

Loftin’s skill was quickly recognized and he moved into the front ranks of Hollywood’s stuntmen, serving as stunt coordinator for several classics of action cinema: The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause and Bullitt. On these famous sets, he discovered that dealing with movie stars’ egos could be as difficult as the stuntwork itself.

“In The Wild One, Marlon Brando and I got off to a bad start,” says Loftin. “I told Brando and co-star Lee Marvin that we had no insurance on the bikes, so they couldn’t take them off the lot. `Screw \ou!' Brando said and he didn't speak to me for about a week before the picture started." But the temperamental Brando admired Loftin's riding skill and after the stuntman taught the actor how to spin a figure eight on a Triumph, the two men became good friends.

Loftin went on to work with Clark Gable and Clint Eastwood. Recently, he drove a stock car for the racing scenes in Days of Thunder. At every step in his long career, he's followed one rule: Never do anything that can't be done twice in the same day-"Even if it might take another car or motorcycle to do it," Loftin laughs.

J.N. ROBERTS

RIDING OFF THE ROOF OF A 10story building, crashing through plate glass and skidding across the path of an oncoming semi is all in a day's work for J.N. Roberts. The stuntman doubled Charles Bronson in The Mechanic and led the chase scenes in Electra Glide in Blue. In the 1 970s, Roberts worked on action TV shows such as "CHiPs." "The Streets of San Francisco" and "The Mod Squad."

Throughout his long career, there's rarely been a dull moment: "One of the gags I had to do involved jumping a 90-foot ravine that was 40 feet deep. I cleared it by about 6 feet. If I hadn't of made it, I would have died. It was a real heart-stopper."

Like many stuntmen, Roberts was a racer first, a legend in California desert competition, rarely losing. He broke into the stunt scene on a different kind of steed-horses-and did several westerns before he could prove his ability on a bike.

Once he did, filling in when Bud Ekins or Ronnie Rondell weren't available, he had more work than he could handle.

Occasionally, he had to just say "no" to an overzealous producer who wanted to save money. "I remember one episode of "The Streets of San Francisco" where I had to take a bike off a pier. They wanted to tie a string around my leg and attach it to the bike so they could find the bike when it went into the water," recalls Roberts. "There was no way I was going to let them do that!"

Although Roberts came through most of the bike gags unscathed, he has had his share of bad luck. One incident on the set of the movie Speed Limit 65 nearly put his eye out. "Here I come down the road and bail off the bike," says Roberts. "The bike hits a car, bounces back and falls on top of me. I had about 40 stitches."

Former desert racer J.N. Roberts was one of many Hollywood stuntmen who took part in filming Days of Thunder.

DEBBIE EVANS

DEBBIE EVANS DIDN'T FLINCH when, at age 19, she decided to become one of the first women to do motorized movie stuntwork. Evans had been riding tri als bikes since she was 6. "1 just showed them I could do those things," she states simpiy.

It wasn't the first time she had taken on a man's world. An accomplished rider, Evans had already competed for Yam aha in both national and international trials events and came in fourth in the 175 class in the Scottish Six Days.

"People over there were laughing at me," says Evans. "They were making bets on how long I would last. That real ly motivated me when I was going through the bogs. My calf muscles were cramping up, but I was determined to go on."

That same strong sense of determination has served her well on movie sets. From her first film in 1977, Deat/isport with David Carradine, to more recent stunts on the TV show "Amazing Stories," Evans never let the danger daunt her. While doubling for Linda Carter in the "Wonder Woman" series, Evans did a jump over a 9-foot fence. "The fence was supposed to be around a junkyard, so they had smashed-up cars piled right up to the height of the fehce. When the cam eraman wanted to know where I was going to land, I drew a red dot on the spot. I did the jump and when I landed, my rear tire was right on the mark I'd made."

Her accuracy helped a lot when she doubled Whoppi Goldberg in the movie Burglar, rode a motorcycle over a Volkswagen and through a wall of fire in The Jerk and took a bike into a swimming pooi in 1994's hit The Beverly Hillbillies.

"I enjoy the adrenaline rush of stunts-being able to do something I'm really good at and get paid for it," says Evans. "It thrills me to no end to have the police blocking off the street and I come down and do my thing-something I'd normally get thrown in jail for."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue