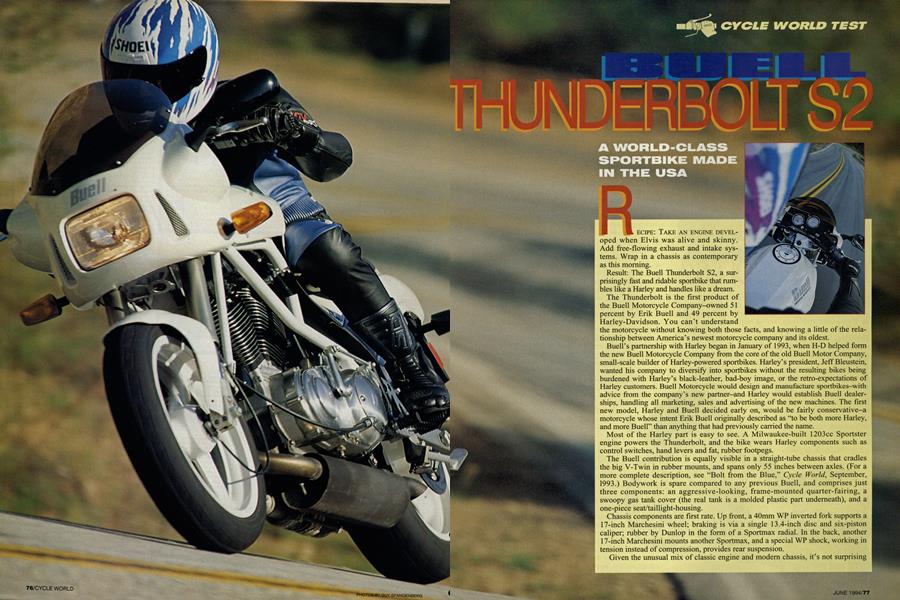

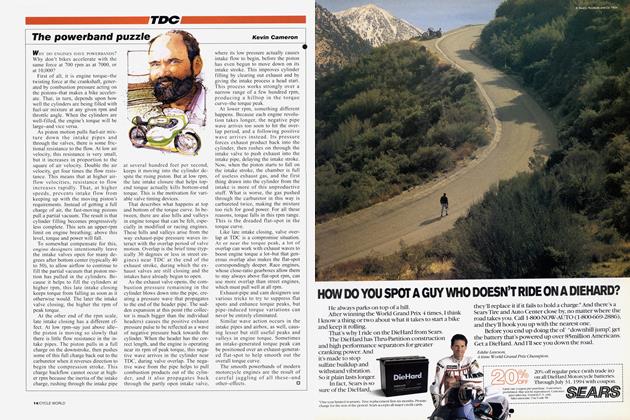

BUELL THUNDERBOLT S2

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A WORLD-CLASS SPORTBIKE MADE IN THE USA

RECIPE: TAKE AN ENGINE DEVELoped when Elvis was alive and skinny. Add free-flowing exhaust and intake systems. Wrap in a chassis as contemporary as this morning. Result: The Buell Thunderbolt S2, a surprisingly fast and ridable sportbike that rumbles like a Harley and handles like a dream. The Thunderbolt is the first product of the Buell Motorcycle Company-owned 51 percent by Erik Buell and 49 percent by Harley-Davidson. You can't understand

the motorcycle without knowing both those facts, and knowing a little of the relationship between America’s newest motorcycle company and its oldest.

Buell’s partnership with Harley began in January of 1993, when H-D helped form the new Buell Motorcycle Company from the core of the old Buell Motor Company, small-scale builder of Harley-powered sportbikes. Harley’s president, Jeff Bleustein, wanted his company to diversify into sportbikes without the resulting bikes being burdened with Harley’s black-leather, bad-boy image, or the retro-expectations of Harley customers. Buell Motorcycle would design and manufacture sportbikes-with advice from the company’s new partner—and Harley would establish Buell dealerships, handling all marketing, sales and advertising of the new machines. The first new model, Harley and Buell decided early on, would be fairly conservative-a motorcycle whose intent Erik Buell originally described as “to be both more Harley, and more Buell” than anything that had previously carried the name.

Most of the Harley part is easy to see. A Milwaukee-built 1203cc Sportster engine powers the Thunderbolt, and the bike wears Harley components such as control switches, hand levers and fat, rubber footpegs.

The Buell contribution is equally visible in a straight-tube chassis that cradles the big V-Twin in rubber mounts, and spans only 55 inches between axles. (For a more complete description, see “Bolt from the Blue,” Cycle World, September, 1993.) Bodywork is spare compared to any previous Buell, and comprises just three components: an aggressive-looking, frame-mounted quarter-fairing, a swoopy gas tank cover (the real tank is a molded plastic part underneath), and a one-piece seat/taillight-housing.

Chassis components are first rate. Up front, a 40mm WP inverted fork supports a 17-inch Marchesini wheel; braking is via a single 13.4-inch disc and six-piston caliper; rubber by Dunlop in the form of a Sportmax radial. In the back, another 17-inch Marchesini mounts another Sportmax, and a special WP shock, working in tension instead of compression, provides rear suspension.

Given the unusual mix of classic engine and modem chassis, it’s not surprising that the Thunderbolt hits you quickly with its uniqueness. Thumb the starter, and its big V-Twin rumbles to life, lowspeed vibration shaking the top of the windscreen in a famil iar Harley blur. Pull away, and as engine speed increases, the rubber mounts get the upper hand on the big pistons. By 3000 rpm, the Thunderbolt is being thrust forward by an irresistible, pulsing midrange, and vibration has been rele gated to brief intervals of tolerable resonance-nothing like the quaking of a standard 1200 Sportster. The Thunderbolt clicks smoothly and quickly between gears in unHarley-like fashion, and accelerates harder

than it has a right to. Between 3000 and 5500, the big Twin thumps out strong, instantaneous

power. It covers the quarter-mile in 12.34 seconds at 108 mph, and tops out at

128 mph. Those numbers place it in performance territory bracketed by the BMW RI 100RS and

the Ducati 900SS. The Thunderbolt comes by its midrangeheavy power hon estly: through pure displacement, and through particular iy free-breathing and quiet exhaust and intake sys tems. The Buell muffler is enor mous, a big and efficient oval can tucked under the engine. At peak

power, this exhaust system allows back pressure to build to only 1.5 inches of water, a tiny fraction of that created by a Sportster's stock and potato-like "shortie duals." This lack of restriction has elevated the engine's power from bottom to top, and only standard Sportster camshafts and ignition curves hold back an even larger peak power potential. The big muffler, Buell sources say, flows well enough to support another 25 percent increase in power-quietly. Expect the Buell equivalent of Harley's Screamin' Eagle hop-up parts to unleash that potential. The Thunderbolt, though, wasn't built for dragstrip sprints. Instead, it lives for backroads. The short wheelbase, steep geometry and forward weight distribution (the rear-axle-to countershaft distance on the 54.6-inch Thunderbolt is the same as on a 60-inch Sportster; the difference in length all comes between the front wheel and engine) have produced a bike that turns corners as quickly as a 600cc sportbike, and with only slightly greater effort. The Thunderbolt has ground clearance to burn, and only steely determination will bring footpeg tips to asphalt. To touch anything hard-mounted would require the bike to be fitted with slicks-and put your elbows at risk. Once leaned, the bike combines stability with an unusual ease in changing line; the Thunderbolt handles blind, decreasing radius corners with world-class aplomb. On a fast and twisty backroad, the Thunderbolt will haul ass without working the gearbox. Put it in third or fourth gear, rely on that lusty midrange, and you can hustle the Thunderbolt along as fast as anything, without working up a sweat. The front disc, for all its singularity, provides excep tionally strong braking, and even mountainous descents fail to fade it. The Dutch-made WP suspension, set on the

firm side, works best with increasing speed or bumpi ness; it transmits small irregularities such as expansion joints to your backside, while swallowing big jolts whole. One of the few chinks in the Thunder bolt's backroad armor appears when you reach an exceptionally tight corner. If it requires a downshift to second, you'll find the gear spacing of the Harley box slightly wonky for a sportbike. With a too-large separation, the gearbox pro duces a brief speed range where you're turning too slowly in third for strong acceleration, yet where a downshift to second buzzes the engine excessively. Overall, though, the Thunderbolt slices through the curves with ease and grace. Part of that comes from the Buell's size and weight. At 457 pounds dry, and with a 31.2inch seat height, it's a relatively light and low bike to be displacing 1200cc. With a fairly upright

seating position, and with footpegs a few inches forward of a typical sportbike, the Thunderbolt feels familiar to anyone who’s ever ridden an English Twin. The combination of size, weight, torque and riding position harks back to the Triumph Bonneville, and offers the same kind of userfriendly performance that made that English bike so popular throughout the Sixties.

Ergonomically, though, the Thunderbolt isn’t an unqualified success-but not through any lack of trying. When originally delivered to Cycle World, the S2 carried low bars that leaned its rider far forward. Combined with pegs about 3 inches forward of being directly under the rider’s center of gravity, the overall effect was a little like being shoved butt-first into a trash can. The pegs, too, were slightly high for the long-range comfort of long-legged riders. A brief conference with Buell followed, and-despite production already having started-changes were made. Our test bike went away, and soon came back with a set of higher handlebars, and lower footpegs, both of which will be offered as no-cost options to Buell customers at the time of purchase. The new bars are aimed at highway comfort, leaning you forward only slightly, while the pegs are a mixed benefit; they offer more legroom, but-mounting in the original location through an offset design-are wider than the original ones, and can bring the knees of riders 6-foot-2-or-taller into contact with the carbon-fiber air cleaner. The Thunderbolt’s seat, too, sets a little hard after a few hours on the highway.

Fortunately, Buell is committed to offering motorcycles that can be tailored to their owners. Some of that will come with a complete line of factory accessories, ranging from touring-oriented parts-such as fairing lowers, a higher windshield and touring seat-to high-performance options such as a rear-set footpeg kit and engine hop-up parts. The rest of that tailorability will come with the flexibility allowed by manufacturing machines in relatively small quantities with both factory and design center located in one building. As just one example, surveys of riders who participated in Buell demo rides during Daytona Bike Week are already affecting the exact bend of the low handlebar to be offered.

Other features of the Buell come not from surveys, but from the company’s preference for simple, engineeringdriven solutions to problems. The sidestand and muffler are good examples. The Thunderbolt sidestand appears a long, ungainly piece to some eyes, folding back against the swingarm like the bolt-on stand of a KTM enduro model. But for good reason: It’s designed to never let the Thunderbolt fall over. The stand locks into place when weight is put on it; even parked downhill, the Thunderbolt can’t roll off it. And the stand’s length and large footpad offer the leverage and surface area to keep the Thunderbolt upright even on brand-new asphalt in the heat of an August day in Death Valley. Similarly, the big oval muffler flaunts convention, and doesn’t have the quick visual appeal of chromed Conti megaphones wrapping up the sides of a Ducati. But in exchange, the Buell system offers practically unlimited ground clearance and produces the strongest running streetbike that’s ever been powered by a factory-spec Harley engine.

This flaunting of convention, even if it was sportbike convention, made some of Buell’s new partners at HarleyDavidson nervous. But as the Thunderbolt has evolved, so have attitudes within Harley. Says Ann Tynion, HarleyDavidson’s Vice President of Brand Marketing, “Buell stands on its own, and is positioned for an entirely different sort of rider (than H-D). It’s targeted at a very specific customer in the performance segment. For Buell, everything is very different.”

So Thunderbolts will be sold at Buell dealerships (even if the first of these will also be Harley dealers). One-inch handlebars and Harley’s bulky switchgear aren’t long-term Buell requirements, and the Thunderbolt will evolve to fit the needs of its own riders unconstrained by Harley and its designs. What will be maintained from Harley are those traditions that will also work for Buell: attention to the customer, concern for quality of manufacture, care for continuity and resale value.

So consider the Thunderbolt S2, the first machine from Buell Motorcycles, the product of dynamic tension. Tension between a classic, torquey engine and a modern chassis. Tension between Buell innovation and Harley-Davidson conservatism. Tension between the visual expectations of motorcyclists and the physics of what works.

But most of all, consider it this: an American sportbike that need offer no excuses.

EDITORS' NOTES

MADE N AMERICA: FOR SOME, THOSE words alone may be enough. But it takes more than just the guarantee that a bike is born in the USA to persuade me to plunk down 12,000 greenbacks. I love Harleys for their classic combi nation of meaty torque and low, lean styling -not because they come bun dled in red-white-and-blue. So the fact that the Buell Motorcycle

I (4~' I ULI5L II Company's first product proudly proclaims its American heritage with a sticker placed prominently on the tank, while compelling, wasn't enough to convince me. But a first ride aboard the Thunderbolt was. Long an admirer of the gutsy Sportster 1200 engine, I expected the big V-Twin to impress. But the Thunderbolt's ability to flash lightning quick through corners was a revelation. A Sportster engine with sporty handling? A winner-in any language, from any country.

Brenda Buttner, Feature Editor

I SPENT MY FORMATIVE YEARS LUSTING over V-Four Hondas, featherweight GSX-Rs and aluminum-framed Ninjas, but over the past 10 years, my prefer ences have gravitated towards Twins. If for nothing else, then, the Thunder bolt-and its free-breathing, 45-degree V-Twin-has my attention. Given the opportunity, I would make a few changes. I like the swoopy

bodywork and tube frame, but the Harley-spec footpegs, levers and clumsy switchgear do not belong on this motor cycle. A bit more seat foam would also be appreciated, and function aside. the kickstand looks as if it belongs on an enduro bike; maybe a coat of paint would help. Hard-edged sportbike riders may scoff at the Thunderbolt's old-tech engine and single-rotor front brake, but rest assured, the Buell is fully capable of straightening a favorite stretch of twisties. As good as it is, though, I think I'll wait for the Real Thing, a Buell-framed VR1000. -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

IT'S TOUGH TO SAY WHAT'S MORE important: What the Buell Thunder bolt is or what it represents. What it is, is an exciting-to-ride, fun-to-look-at, sporting V-Twin. You can argue-and I'd agree-that the Buell still has a bit too much kit-bike aura about it; the carbon-fiber pieces could be better done and the hex-nutted mesh screens flanking the headlight and tail-

light look decidedly cheesy. Also, for $1000 more, Twins lovers can step up to Ducati's 888, which delivers V-motor individuality and truly leading-edge performance. But never mind that. Buell has nailed the basics with the S2. and per formance help is as close as a 1-800 phone call-praise the Lord and pass the aftermarket catalogs. As to what the Thunderbolt represents: Harley-Davidson. which understands its customers better than any other man ufacturer, now wants to be a player in the sportbike market. If I were the other bike-makers, I'd pay very close attention. -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

$11,900