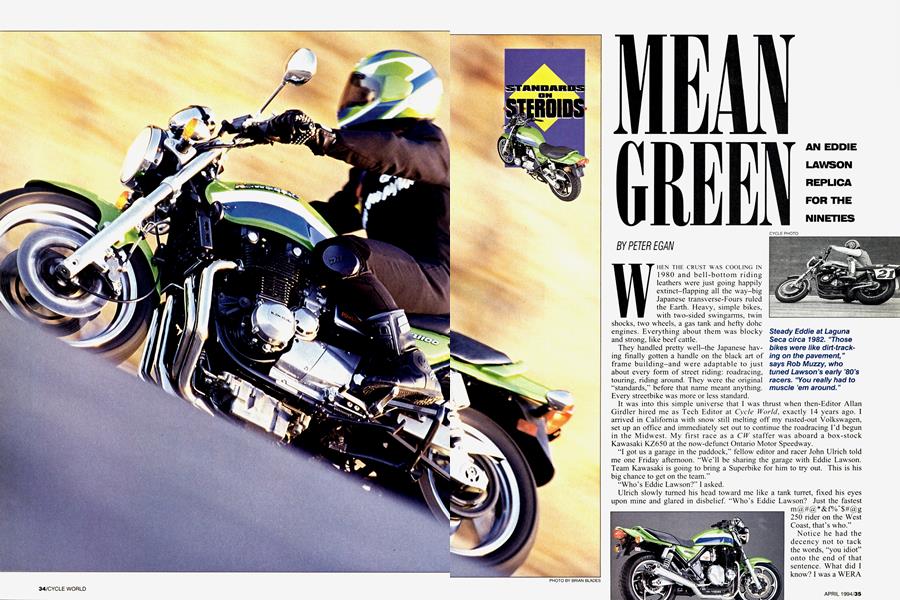

MEAN GREEN

AN EDDIE LAWSON REPLICA FOR THE NINETIES

PETER EGAN

WHEN THE CRUST WAS COOLING IN 1980 and bell-bottom riding leathers were just going happily extinct-flapping all the way-big Japanese transverse-Fours ruled the Earth. Heavy, simple bikes, with two-sided swingarms, twin shocks, two wheels, a gas tank and hefty dohc engines. Everything about them was blocky and strong, like beef cattle.

They handled pretty well-the Japanese having finally gotten a handle on the black art of frame building-and were adaptable to just about every form of street riding: roadracing, touring, riding around. They were the original "standards," before that name meant anything. Every streetbike was more or less standard.

It was into this simple universe that I was thrust when then-Editor Allan Girdler hired me as Tech Editor at Cycle World, exactly 14 years ago. I arrived in California with snow still melting off my rusted-out Volkswagen, set up an office and immediately set out to continue the roadracing I'd begun in the Midwest. My first race as a CW staffer was aboard a box-stock Kawasaki KZ650 at the now-defunct Ontario Motor Speedway.

"I got us a garage in the paddock," fellow editor and racer John Ulrich told me one Friday afternoon. "We'll be sharing the garage with Eddie Lawson. Team Kawasaki is going to bring a Superbike for him to try out. This is his big chance to get on the team." "Who's Eddie Lawson?" I asked.

Ulrich slowly turned his head toward me like a tank turret, fixed his eyes upon mine and glared in disbelief. "Who's Eddie Lawson? Just the fastest 250 rider on the West Coast, that's who." Notice he had the decency not to tack the words, "you idiot" onto the end of that sentence. What did I know? I was a WERA racer from the Midwest, and I didn’t spend my time scanning AFM race results from Southern California.

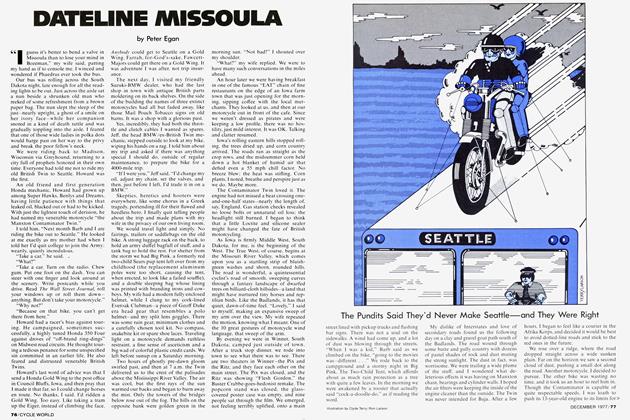

So this big deal Eddie Lawson showed up at our garage, a skinny, modest kid who said very little. He shook hands and merely nodded when we were introduced. His attention was riveted on a green KZ1000 Superbike being unloaded from the official Kawasaki cube van. A big, mean-looking chunk of bike with a cut-down saddle and numberplates. The bike exploded to life with a violent racket in the small garage, Lawson climbed on, Hipped down his visor and headed out for practice.

He came back about 20 minutes later with his eyes red, pupils dilated and a strange, fixed grin on his face, like someone who has just fallen 30,000 feet from an exploding airliner and landed safely on a haystack.

“Man, the horsepower..." he said, over and over again. It was the beginning of great things.

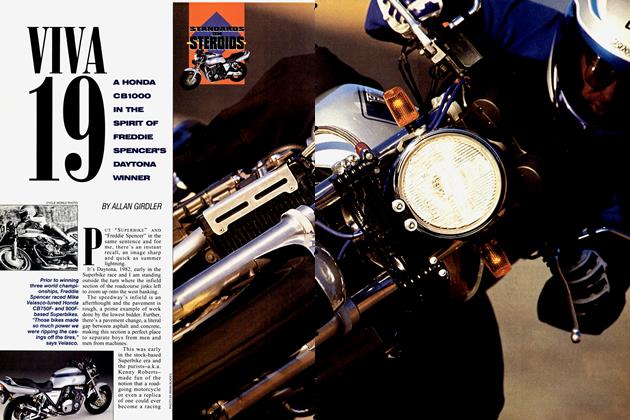

Lawson and that bike symbolize the era for me, so I was quite happy to return to California recently-14 years from the exact date of my first day on the job here-to see what Cycle World had wrought in creating a modem iteration of the Lawson Replica.

The original Eddie Lawson Replica (ELR) was introduced as a 1982 production model, the KZ1000R, to celebrate Lawson’s first AMA Superbike championship. It was essentially a standard KZ1000 with apple-green paint, small fairing, Kerker 4-into-l exhaust, reservoir shocks, oil-cooler, a black engine and gold-trimmed wheels. It sold for $4400 and turned a 12.11-second quarter-mile at 112.07 mph.

There was also a “real” ELR, the KZ1000S1, made in limited numbers for serious roadracers. This $10,999 beauty duplicated many of the modifications tuner Rob Muzzy had lavished on Lawson’s and Wayne Rainey’s bikes (now there was a team) and cranked out 136 horsepower at the crank-if you got a well-assembled one. Lawson’s own team bike was said to be good for 149 horsepower.

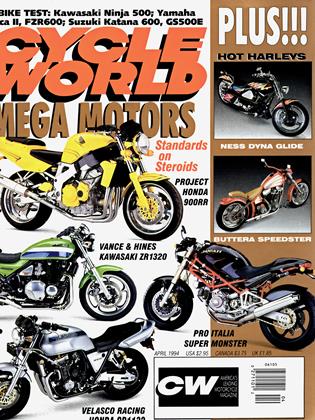

In keeping with this grand tradition of green paint and chain-stretching blockbuster horsepower, Cycle World commissioned Vance & Hines (who incidentally teamed up the same year Lawson joined Kawasaki) to build us the modern equivalent, based on a 1993 Kawasaki ZR1100 standard.

So what did they do to the bike, you ask, given this fine blank slate?

Well, in the more-is-better department, they installed 82mm pistons and liners with a 10:1 compression ratio, raising the displacement to a heady 1320cc.

Carrillo rods were assigned the job of keeping these pistons in the same dyno room as the crank. Ports were opened up and polished to meet the Mikuni 40mm Hat-slide carbs, and .438lift, 258-degree camshafts were fitted, lifting titanium valve retainers, competition springs and competition-grind valves.

Downstream, it got a racing clutch, undercut gears, a VHR “Classic Performance” 4-into-l exhaust system. A VHR Powerpack ignition system was used. Total cost of these engine modifications: $3700.

That’s a lot of money, but it paid off on the V&H dyno. The engine cranked out 170.2 horsepower at 9750 rpm and 103.5 foot-pounds of torque at 8000 rpm, measured at the countershaft, with velocity stacks. Even with airbox in place and hooked up to the CW rear-wheel dyno, our bike produces 136.1 horsepower at 9500 rpm with 84.7 foot-pounds of torque at 7000 rpm.

This, friends, is serious horsepower. Especially when you consider that a stock ZR 1100-no slouch itself-musters up “only” 85 horsepower and 61.1 foot-pounds of torque at the rear wheel, at 8000 and 6750 rpm, respectively. What we’ve got here, if numbers from the old days can be believed, is quite a bit more than Eddie had to work with in 1982.

The chassis, meanwhile, got a thorough going-over by White Brothers: a reworked front fork with new bushings and progressive springs; Russell braided brake lines; Spectro 20-w'eight fork oil; and heavy-duty WP shocks. All for an added cost of S791. So now we have a total of $4491 in modifications, added to the $6999 list cost of the stock 1993 ZR1100. An $11,490 motorcycle. The ZR was discontinued for 1994, of course, so bargains may be available at dealers. Used ones cheaper still.

So how does this big green pleasure machine run? To find out, I flew into Southern California from snowinfested Wisconsin (no rusty Volkswagen this time) and joined my friend and former Editor Allan Girdler for a twoday ride in the mountains. He would ride a Freddie Spencer Replica Honda CB1000, and 1 the Kawasaki. On a sunny Tuesday morning, I threw a leg over the big ZR and hit the starter button. A moment of choke lights the engine with a bark and a whoop, after which it settles down to a deep sizzling idle that sounds like a malevolent arc welder, if arc welders used electrodes the size of broomsticks.

Warm-up takes no time at all. You snick it into gear, lean slightly over the handlebar to keep the front end down, release the quite heavy clutch lever, twist the quite heavy throttle and accelerate down the road like something from an overwrought Steppenwolf song, which is to say you fire all of your guns at once and explode into space, in a manner of speaking.

What all this unavoidable hyperbole might suggest is a difficult, barely ridable monsterbike for masochists, but nothing could be farther from the truth. The powerband is flat as Nebraska, carburetion is spot-on, steering light. Except for the stiffness of clutch and throttle (which you soon quit noticing) the reborn ZR is as easy to ride in traffic as any big-bore Stocker. Even the exhaust note is civilized. It puts out a rich, euphonious growl, but the sound is subdued enough that you can wick it up in town without offending. An almost perfect balance between noise and music.

In short, the ZR1100 is the one of the most refined bighorsepower bikes I’ve ridden. Brutishly fast yet quite controllable, it’s an almost-normal motorcycle whose twistgrip happens to be a wish-fulfillment device of the highest order.

Freeway cruising is relaxed and smooth, 4000 lazy rpm showing on the tach at 70 mph. A nudge on the throttle rockets you into any traffic opening instantaneously, like Nature abhorring a vacuum. The seat is wide and comfortable and the bar tilts you forward at exactly the right angle to prevent the dreaded sail effect, even at 90 or 100 mph.

You can ride this bike all day, and could tour on it without any misgivings.

Handling? In the twisties, you sit in the middle of the saddle nearly upright with knees and elbows slightly out, counters teering effortlessly through the medium-wide Superbike-style bar to make the horizon tilt, meanwhile applying massive amounts of horsepower to the pavement through the fat back tire like a painter with an oversized brush. The engine simply extrudes horsepower and acceleration in seamless waves, blasting you from one hilltop to the next with ridiculous nonchalance. It’s as if the inertia of a

high-speed passenger train had been compressed into a small, dense package. This power flows abundantly from every part of the tach between 2500 rpm and the 9500-rpm redline, in any gear. It’s almost a drug.

And, of all things, the ZR is easy to ride on dirt roads. We stayed the night at Allan’s mountainside home and orange grove in the wilds of the southern coastal range, descending to his house on

a series of glorified dirt goatpaths that would have the average sportbike rider clutching his clip-ons for life itself. But the leverage of those wide Superbike bars-and rider weight over the pegs-made it easy, like riding an old TT bike.

On our trip down from the mountains up the coast the next day I tried to think what advantage, if any, a current fullcrouch, full-fairing sportbike might have over the ZR Lawson Replica. Other than wind protection in cold weather (with the attendant wind roar around your helmet), I couldn't think of any. I’m convinced that most riders could go just as fast with more confidence, over a wider range of road conditions, on a bike like the ZR-given equal horsepower. Is it possible we are all victims of fashion?

Speaking of which, standard bikes like the ZR1100 are very much in fashion in Japan right now. All the rage, in fact. Perhaps Japanese riders have arrived (for the second time) at some conclusion that has not yet taken full form on this side of the Pacific: These bikes are easy to ride and really fun. Almost too much fun, in this case. Sometimes there is progress in rediscovery. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigher Standards

April 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy A German Bike?

April 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClass Struggles

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupVr Harley Superbike For the Street?

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVr 1000 Parts For the People

April 1994 By Robert Hough