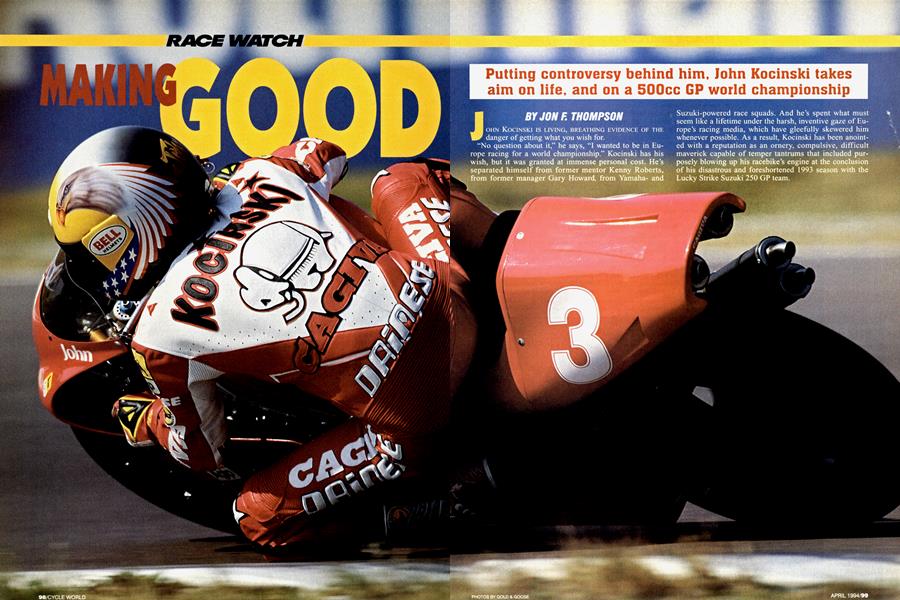

MAKING GOOD

RACE WATCH

Putting controversy behind him, John Kocinski takes aim on life, and on a 500cc GP world championship

JON F. THOMPSON

JOHN KOCINSKI IS LIVING, BREATHING EVIDENCE OF THE danger of getting what you wish for. “No question about it,” he says, “I wanted to be in Europe racing for a world championship.” Kocinski has his wish, but it was granted at immense personal cost. He’s separated himself from former mentor Kenny Roberts, from former manager Gary Howard, from Yamahaand

Suzuki-powered race squads. And he’s spent what must seem like a lifetime under the harsh, inventive gaze of Europe’s racing media, which have gleefully skewered him whenever possible. As a result, Kocinski has been anointed with a reputation as an ornery, compulsive, difficult maverick capable of temper tantrums that included purposely blowing up his racebike’s engine at the conclusion of his disastrous and foreshortened 1993 season with the Lucky Strike Suzuki 250 GP team.

Indeed, 1993 was a pivotal year for Kocinski. He hooked up with girlfriend Toti Latorre, of Barcelona, the year before, and throughout 1993, he’s experienced an awakening. “She’s helped me to realize what’s going around me,” he says, “I’ve got a better connection between myself and the rest of the world.” What was going on around him, he says, were things over which he had no control. He vowed to change that, and he now runs, with Latorre’s help, his own affairs. The result is that, “I’m much happier than I’ve ever been. I’m fortunate to have someone who cares about me. I needed her help.”

He’s also got a Cagiva 594 GP bike, and, he believes, a chance to win the 1994 world championship. “I feel like I’ve got a shot. We’re gonna go for it,” he says.

That he can go for it is, in part, the result of a not-so-careful process of growth and maturation that began when he signed onto the Team Roberts 250 GP team in 1990.

Kocinski is a tidy, compact man of 25. If that seems young, well, it isn’t. Kocinski’s gone from the local dirttracks around Little Rock, Arkansas, his home town, to the racing capitals of Europe. What now peers out at you from his face is 20 years of hard racing experience made even harder by the fact that racer years are like dog years-each worth maybe seven of those of normal mortals.

Aided by his father, Jerry, a Little Rock motorcycle dealer and former racer, Kocinski started racing dirttrack at 5, and by the time he was 12, he says, “I had a vision of being a motorcycle racer.” He began roadracing at 14, made the jump to Superbikes at 15, turned Pro at 16. “But I knew Superbikes weren’t what I wanted to do,” says Kocinski, who prefers the lightweight quickness of racebred equipment. At 17, he rode his first 250 GP bike. He liked it.

He hooked up with Kenny Roberts, moved to a small apartment in Modesto, California, so he could train at KR’s ranch, and began racing for Roberts in 1987. The arrangement worked, as well it should have. Indeed, Cycle World noted in a May, 1990, story that because of his style and brashness, Kocinski was considered by some to be “the second coming of King Kenny.” After winning three straight AMA 250 roadracing championships, he went to Europe for the 1990 season with Roberts’ Marlboro Yamaha team and promptly won the 250 GP world championship. His long-term goal was racing’s Holy Grail, the 500cc GP circuit. His chance came in 1991, when he was moved by Roberts to partner Wayne Rainey on the 500 team.

What should have been Kocinski’s big chance turned out otherwise, partly because of a shoot-from-the-lip, smart-ass cockiness that made him the butt of Roberts’ paddock jokes, and which earned him the critical attention of the European media, and partly because his riding style was different from Rainey’s.

His mouth started his troubles with the press. He called fellow 250 competitors “pussies,” and was overheard to remark that “If you’re not American, you ain’t shit.” The first remark, he now says, was made privately and in jest. The second, he says, was made in frustration borne of being outpowered on a horsepower track by a Japanese rider aboard a Honda.

“I know I had a bad attitude,” Kocinski admits, “I didn’t care about anything or anybody. I was going to win, and nobody was gonna stop me. My attitude didn’t help me with the media. I had a lot of confidence, that’s why I was so outspoken. It came back to bite us on several occasions. You learn a lot.”

Doing the biting, Kocinski says, was a vengeful pack of newshounds intrigued by his fastidious personal habits. How fastidious is he? Did he, for instance, launder his motorhome’s curtains so many times, as reported in the European media, that they faded and shrank? Did he, as also was reported, move his furniture onto his lawn in the wee early morning hours to blow the dust off it with an airhose? Both reports, he says, are false, though he does allow that, “I keep my things up more than anyone else I’ve been around.

“I know I was difficult to be around,” Kocinski adds, “I’ve learned about life the hard way.”

One of the things he learned was that he wasn’t in control of his own affairs. After his 1990 250 GP season, Kocinski says, in spite of his desire eventually to race 500s, he expected to stay in the 250 class to defend his newly acquired number-one plate. Instead, he was moved to a Team Roberts 500 ride. He learned of this change, he says, in midJanuary 1991-too late for him to complete the physical training required to ride a 500 well.

“You need strength and endurance. You’ve never got enough of anything physical to really ride one of these things,” Kocinski says of the 500s.

But strength and endurance weren’t his only worries. He also worried about problems which resulted, he says, from the difference between his riding style and that of Rainey.

“I learned quickly I couldn’t get the bike to go the way I wanted it to go.

It wasn’t built for the way I wanted to ride it. It was built for Rainey. He took different lines than I did; he’d brake hard deep into a corner, turn it, and accelerate out. I brake earlier and not as hard, and carry more corner speed. Wayne deserved to get what he needed. I sure wish somebody would have told me very clearly I wasn’t going to get what I needed. I'd have done something else,” he says.

Though he finished the 1992 season third in the 500cc point standings, doing something else became reality for the 1993 season. Koeinski signed with the Suzuki 250 GP team after being replaced on the Roberts Yamaha squad by Luca Cadalora in the wake of team recriminations over the results of winter testing.

Koeinski says, “When you're third in the world championship, you don't go back to 250s.” He’d been contacted by Cagiva and, he says, “Toti told me to take the Cagiva ride. I didn’t listen. I’ll regret that for the rest of my life. At that time, 1 still had a lot of trust in my management and I didn't have enough confidence in myself to go in that (Cagiva’s) direction,” he says. Then he thinks for a moment, and adds, “I was in a mafia. My management company also handied Kenny and Rainey. How is it possible for your manager to be your manager when he’s also working for the team owner? It’s a total eonflict of interest. Is that even legal?”

His Yamaha experience behind him, Kocinski soon found that the Suzuki team wasn’t going to be a piece of cake.

He says, “After the third race, Toti recommended we get out. It was clear we weren’t going anywhere.” But getting out wasn’t possible. Nothing came of his requests to his manager, he says, and adds, “I didn't have enough control of my own situation.”

Though the little Suzuki was woefully underpowered, Kocinski rode the wheels off of it until the weekend of the Dutch TT at Assen. There, his deal with the team expired in the biggest possible way: He was accused of purposely blowing up the bike's engine on the cool-off lap, and of avoiding, in a temper tantrum, his third-place step on the podium.

“Do you believe that?” Kocinski asks, shaking his head. He explains, “On the cool-off lap, the primary sprocket and the chain came off. I turned the bike off with the kill switch and coasted off the track. There was nothing else wrong with the bike, no oil leaking or anything. Assen’s a long track, and I was still two or three corners from the pit entrance. I walked about three-quarters of a mile before the car showed up to pick me up, and I was mad about that.

I could hear the announcements from the podium and I knew I was too late for the ceremonies. I missed them. But I didn’t purposely miss them. That first report that I blew the bike up came from one of my mechanics. He hadn’t even seen the bike. Can you believe that, that a mechanic on your team would say that?” He shakes his head, incredulous at the thought of such treachery.

The ensuing blowup between Kocinski, his French Suzuki team manager-with whom he’d been feuding publicly-and the European press brought an end to his deal with Suzuki, and it brought him a three-race layoff. During that time Cagiva expressed renewed interest in Kocinski, and he signed an agreement to do two races with an option for two more.

As soon as he climbed aboard the Cagiva, Kocinski says, two things were obvious. First, the bike responded to his style of riding. And second, “When you’ve been off a 500 for two weeks it feels like an eternity, so you can imagine what one feels like when you’ve been off them for a year. It took me some time to get adjusted. Our success (Kocinski recorded two fourth-place finishes, won the USGP, and crashed out of the lead in Spain when another rider fell in front of him) just shows how good the bike is, and how good Cagiva is.”

Kocinski adds, “With Cagiva I know that I can win. These are very dedicated people, the best I’ve ever worked with.”

What does this mean for 1994, for GP racing, and for John Kocinski?

He says, “I think 1994 is going to be a very positive year for myself and for Cagiva. I think, yeah, I can win a championship. And if I can, I will.”

What about Schwantz, Doohan and the rest? Is Kocinski forgetting about those guys?

No way. Racing’s once-brash, trashtalking bad boy seems to have been tempered by the heat of racing’s fires, and also by the warmth of an important relationship, into a thoughtful, serious adult who carefully says in response to the question, “I don’t know. There are a lot of great racers and a lot of good teams. It’s hard to call what’s gonna happen.” He thinks for a moment and he adds this coda: “I feel like I’ve prepared all my life for this.

I won’t ever be successful until I’m 500cc world champion.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigher Standards

April 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy A German Bike?

April 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClass Struggles

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupVr Harley Superbike For the Street?

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVr 1000 Parts For the People

April 1994 By Robert Hough