THE LAST BEATNIK

The life and times of VonDutch

JON F. THOMPSON

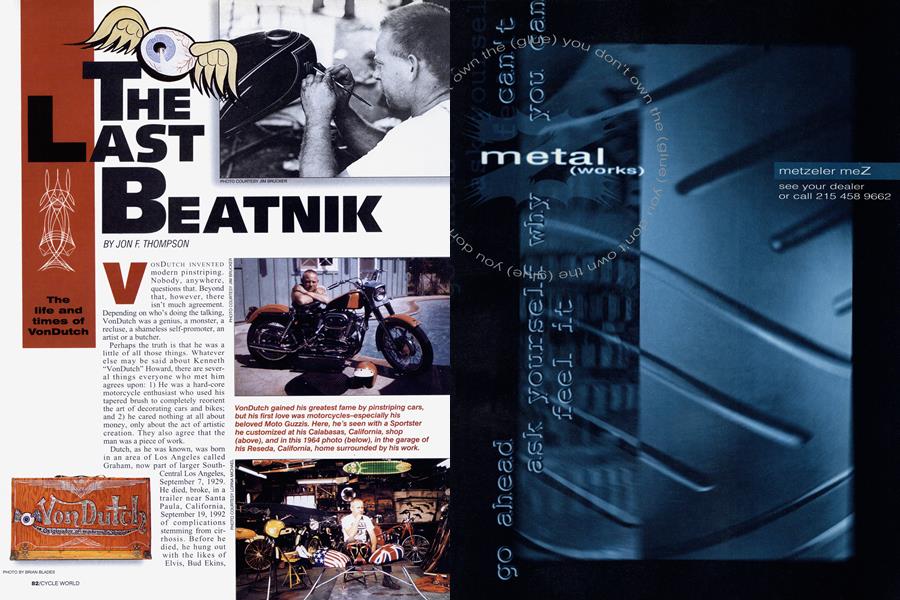

VONDUTCH INVENTED modern pinstriping. Nobody, anywhere, questions that. Beyond that, however, there isn't much agreement.

Depending on who’s doing the talking, VonDutch was a genius, a monster, a recluse, a shameless self-promoter, an artist or a butcher.

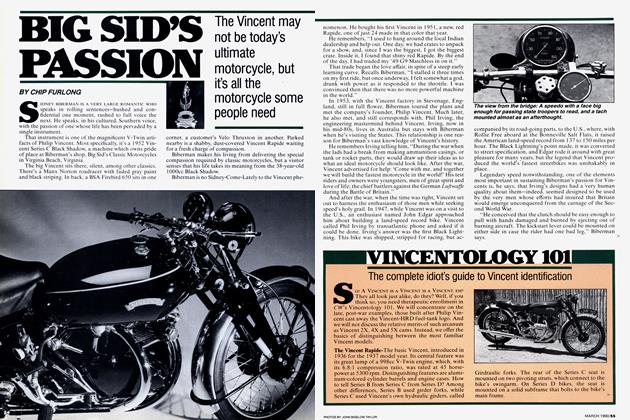

Perhaps the truth is that he was a little of all those things. Whatever else may be said about Kenneth “VonDutch” Howard, there are several things everyone who met him agrees upon: 1) He was a hard-core motorcycle enthusiast who used his tapered brush to completely reorient the art of decorating cars and bikes; and 2) he cared nothing at all about money, only about the act of artistic creation. They also agree that the man was a piece of work.

Dutch, as he was known, was bom in an area of Los Angeles called Graham, now part of larger SouthCentral Los Angeles, September 7, 1929. He died, broke, in a trailer near Santa Paula, California, September 19, 1992 of complications stemming from cirrhosis. Before he died, he hung out with the likes of Elvis, Bud Ekins, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth and Steve McQueen. And he left a body of work almost as vivid as his legend. It survives in the form of pinstripe jobs on motorcycles and hot-rods, drawings and paintings, hundreds of custommade and highly individualistic knives, a large number of weird firearms, a few belt buckles and helmets, and, for the people he cared the most about, letters bearing hand-painted decorations.

In included ivory, spite it of was his metal, work pinstriping in canvas media and that that he defined, and which largely defined VonDutch. He reclaimed striping from tradition’s dustbin and turned it into an original art form that clamored up onto its own deathbed-according to customizer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth-with Dutch’s passing. Roth says of pinstriping’s heyday in the 1950s, “The standard of cool was set by Dutch. He told me, ‘When I die, pinstriping is gonna die with me.’ And it sure enough did.”

Reports of pinstriping’s death probably are exaggerated, but nobody exaggerates Dutch’s contribution to the art. Says boyhood friend and fellow pin-

striper Bethel Ethridge, “Kenny had the talent, the eye for color, the ability to see design. He had the gift.”

Spence Murray, editor of Rod & Custom magazine during much of hotrodding’s heyday, remembers, “His work was so outlandish and so intricate, and he was such a character-having something striped by VonDutch became kind of like a cult.”

Not a lot of Dutch’s striping remains because it was applied to vehicles that were, to say the least, always subject to change. But the VonDutch legend continues to grow and mutate as it works against its own internal stresses and contradictions.

“He was self-contained, and not a nice person,” remembers Mike Parti, a Southern California restoration specialist who grew up with Dutch and knew him well. “He liked being nuts. He worked at it. He liked being right in your face.”

Temma Kramer, professor of film at California State University at Northridge, also knew Dutch well and recalls, “He was a gentle and very loving friend, basically a kind person.” Dutch worked for legendary motorcycle racer and stuntman Bud Ekins for 14 years, and Ekins remembers, “He was a good guy until he got drunk. Then he was a monster who was proud of Hitler.” And of some of the work Dutch was most proud of, Ekins snorts, “He had his own style, but he was not an artist. He was a butcher.”

“He was like Jekyll and Hyde,” agrees Jim Brucker, for whom Dutch went to work in 1973 after being fired-for the final time in a long succession of firings-by Ekins. “One minute he was the greatest guy alive. The next, he was the worst. He’d start drinking beer in the morning, and by afternoon he’d be what he called ‘turning Tasmanian.’ You couldn't have people around him.”

Whatever else people remember about VonDutch, they all remember this: He was a committed and enthusiastic motorcyclist who associated the freedom of riding, Kramer says, with a sense of penetrating time and distance. He trundled around aboard a BMW Boxer sidecar rig until he died.

“He had motorcycles as far back as I can remember,” says Virginia Reyes, his sister. “He started fooling around (with his painting) on motorcycle tanks, and it just took off.”

Brucker, a collector and rancher who

owned an Orange County, California, museum called Cars of the Stars, where he employed VonDutch's skills, adds, "Motorcycles are kind of like a one-man piece of machinery, and he was a one-man type of guy."

`onDutch, it's said, trust ed machines far more than he trusted people. There was an interesting reason for that, accord ing to Cindy Rutherford, a long-time companion who owns and operates Century Motorcycles in San Pedro, California.

She says, “He figured he was a machine. He said he didn’t have feelings for anything but machines.”

In poignant letters to Rutherford, Dutch mused, “All machines talk to me. They are honest and don’t lie. Could I really be a machine? Some people in my life have been able to hear the gears mesh in my head.” And he signed some of his letters to Rutherford, “Your own personal android.”

Something else that meshed was Dutch’s uncompromising world-view and his respect for what he saw as the organized, regimented nature of all things German. Family members say this began when he was a child, and resulted in young Kenny Howard’s adoption of the name VonDutch.

His sister says, “He had a photographic memory. He could read anything and remember it. When he and his friends were real young, they taught themselves to speak German, and they spoke it to each other. So people started calling him ‘Dutch.’ When he was in his teens, when he started pinstriping, he added the ‘Von.’ It just had a nice sound.”

And what of VonDutch’s other trademark, the flying eyeball, a garish, bloodshot, blue-irised orb suspended between two outspread wings?

“He thought it was neat,” remembers Ethridge. “It was the inner eye, the ability to look inside yourself. It was the conscious, the all-seeing eye. Or maybe it was just a wacky design. It just depended on how he was feeling when you talked to him.”

VonDutch, complete with his flyingeyeball logo and individual approach

to what had been a moribund art form, sprang into the public consciousness in the early 1950s when he began appearing with the likes of “Big Daddy” Roth and others at hot-rod shows around Southern California. He came by the skill he exhibited at those shows naturally. His father was a signpainter-indeed, Dutch worked out of his father’s old paint box all his life. Dutch striped bikes because he loved bikes. His work with cars began almost by accident. He was called to lay some stripes down over an area on a car door where paint had dried to reveal an area gouged with grinder marks.

triping, of course, can be found on ancient horsedrawn vehicles. And until VonDutch came along, stripers painted in the way they always had-they basically outlined body panels. To this, VonDutch added his own special vision, and the intent, he told Kramer, that his lines always relate to the pas sage of air over whatever vehicle he was working on. If he was working around a door handle or a hood orna ment, he'd create with his paint lines a wake of air around and behind it.

His designs could be a lot more offthe-wall than that, however, and often revealed different images or ideas when viewed from alternative angles. The final design often depended upon how Dutch perceived the person paying for the work, as Murray, former editor of Rod & Custom, recalls: “One of my co-workers wanted the dash of his car striped. He paid $25-big money, in those days-left the car, and came back to pick it up. He didn’t see a thing, until he noticed a musical note coming up out of the ashtray. He opened the ashtray and found that VonDutch had painted a symphony orchestra inside.” Or how about this one, recalled by Dick Symonds, a Los Angeles-area British bike specialist who knew VonDutch from childhood: “A guy told Dutch to stripe an oil tank a particular way. When he came back he found the tank striped on the inside. He had to stick a dental mirror down inside to see the striping.” Or this one, from former racer Jim Hunter: “One time he painted a guy’s complete motorcycle—the wheels, tires, tank, bars-all solid red. I think the guy pissed him off.”

In spite of his eccentricities, so complete was acceptance of Dutch, of his mastery of his craft, and of his wild behavior, that the great and not-sogreat flocked to the door of his shop. Sheila Harlan, his ex-wife, remembers that even Elvis showed up. Others came too, in search of the VonDutch touch. Lorna Michael, one of two daughters, remembers, “Once about a hundred Hell’s Angels pulled into our driveway to get a couple of bikes painted. It was pretty wild.”

Harlan says, “He engulfed himself in his work. It was his whole life. He didn’t care about money, he’d never commercialize his art. This bothered me very much. I couldn’t understand why he’d shut the door. Many times the door would start to open, and I’d think, Ts he gonna let it open all the way this time?’ But he never did.”

Make money? Dutch was far more intent on living the life of a bohemian artist. At the same time he was pinstriping, he was making guns and knives, and accomplishing complex restorations that began from little more than boxes of rusty junk. And he was playing music. Reyes, his sister, says he taught himself to play the wind instruments, stringing them from the ceiling above his bed with wire, then lying in bed and playing without having to hold the instruments up. He became thoroughly accomplished, and, whenever he could, sat in with working jazz musicians.

Dutch to Bud the late hitched Ekins’ 1950s, his star working wagon in first out of Ekin’s motorcycle shop in the San Fernando Valley, and later, out of his own shop on Ekins-sponsored projects.

When Dutch was working, Parti recalls, “You’d walk into his shop and he’d say, ‘Six-pack.’ You’d have to go buy beer before you came back.” Kramer remembers that the beer of choice was Miller, for the most VonDutch of reasons: “He told me once he just loved the way they made the M on the label,” she says.

Almost as remarkable as Dutch’s skill with his hands was his speed. He was so fast and so sure of himself that he painted in lacquer, which dries right behind the brush, instead of the slowdrying enamel used by most stripers, which allows mistakes to be wiped away. But Dutch wasn’t just fast with his stripes. Brucker says no matter what the project or medium, “One day something would be just an idea, and the next day it’s reality.”

Ekins recalls, “He worked hard and he was the best for a long, long time, but he did pretty much what he wanted to do. Finally I had to send him to work at home. You just couldn’t have him around the customers.”

Says Symonds, “I remember one time him taking his clothes off at Ekins’, standing on the counter, beating his chest. Bud fired him more times than you can believe.”

Finally Ekins, who had used Dutch’s skills to customize and refurbish battered bikes his Triumph dealership had taken in on trade, fired VonDutch one last time. He says, “I had to get rid of him out of the business. He just plain ran people off. You measure the amount of business he brought in against the pain in the ass he was, and it weighs on his side. But finally, enough was enough. After 14 years I needed a change.”

After the final blow-up with Ekins, Dutch followed up on an invitation from Jim Brucker: “He showed up in his custom Toronado one day at Cars of the Stars, and I said, ‘Come aboard, if you want to.’ A few days later he showed up in that big bus of his and moved in. I was kind of surprised.”

“That big bus” was outfitted as a home/shop. He worked in it, and he lived in it, but it was certainly not built for comfort.

Ed Roth remembers, “His comfort was in working with machinery, not in buying comfort with money. He slept in a bed that was next to his lathe-it had chips of metal in it. His comfort was in creating the things that were in his mind.”

utch's relationship with Jim Brucker, and with Brucker's brother Dan, remained a warm one, Brucker says, in spite of Dutch's antics. He recalls, "He'd go out and harass cus tomers in the museum. He came out one night with a .22 pistol and just ran everyone out. The girls all locked themselves in the ticket booth and called me. We had big pictures of movie stars on the walls-he put 10 rounds into Fred McMurray's nose. I don't know why he picked on McMurray. Anyway, I went down and took him back to his bus. Those were trying times."

In spite of those times, Brucker says, "I really liked him, and he'd say, `Jimmy, I really love you.' It was real touching. We got along good, and I miss him. I'd think of a project for him to do, and he'd think of something 10 times better. It was unbelievable how the guy’s mind worked, he was just pure genius. I’ve never known anybody who had his talent. He could have made a lot of money.”

VonDutch had no illusions about his work, and probably he knew that it was valuable. He appeared not to care. He valued the act of creation, not the finished piece of art, and his prices reflected that. The price for a given bit of work might be a cash sum, or it might be something else.

Says Brucker, “He loved to trade. Money meant nothing to him, but he loved German guns. If you came in with something like a Walther or a Luger, that got his attention. You were all right. If he really liked you, he’d trade you for something.”

So powerful was Dutch’s faith in the concept of mind over matter that he believed, friends say, that he could trade a bit of intellectual energy for improved health. It was an exchange that was doomed. The tragedy is that his health’s long, slow slide need not have happened at all. Brucker says, “If he had conformed, he would have lived to be 100. He was a tough guy. When he got sick, I took him to the hospital. But he hated the hospital’s bureaucracy, and they kicked him out. He wouldn’t let me bring a doctor around until the end. He’d say, T got myself into this mess and I’m gonna get myself out.’”

And now, more than a year after Dutch’s daughters spread the ashes of their father at sea, the legend of VonDutch is being fueled by the established art world that by all accounts he disdained: A major exhibit, called Kustom Kulture and containing work by VonDutch, Roth and others, is making the rounds of U.S. art museums. In an ironic piece of commercialism, viewers can purchase T-shirts emblazoned with Dutch’s trademark eyeball.

Rather than give into commercial and family pressures to do something other than what he wanted to do, Dutch remained a bohemian. Indeed, says Reyes, “He called himself the original beatnik.”

In the end, of course, VonDutch’s genius was shaped for and by the world he perceived whirling around him, but not necessarily for the world he had created for himself. He was a contradictory man who never swayed from his own fierce independence. It was an independence that shaped and redefined an art form. And it was an independence that brought life to one of motorcycling’s most vivid and interesting legends. E2

View Full Issue

View Full Issue