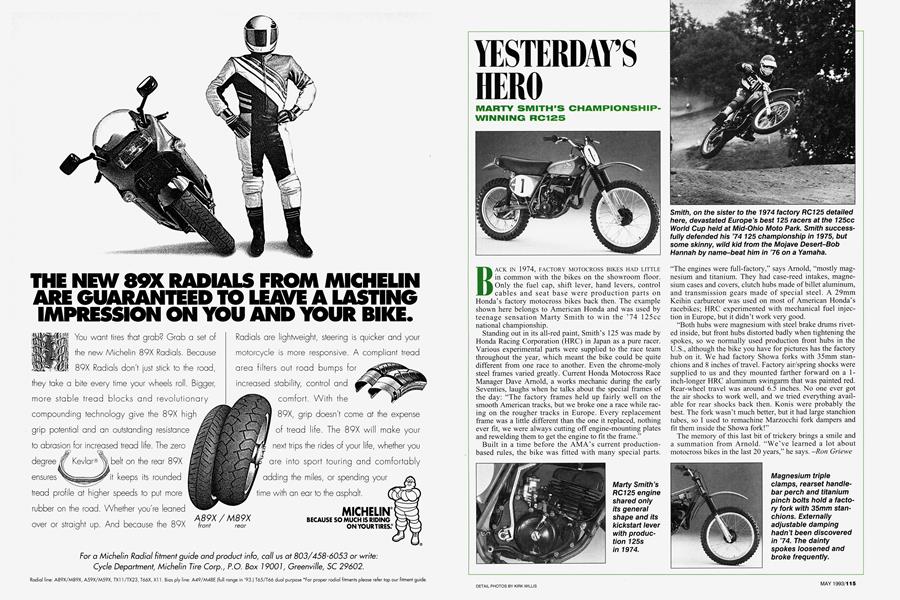

YESTERDAY'S HERO

MARTY SMITH’S CHAMPIONSHIP-WINNING RC125

BACK IN 1974, FACTORY MOTOCROSS BIKES HAD LITTLE in common with the bikes on the showroom floor. Only the fuel cap, shift lever, hand levers, control cables and seat base were production parts on Honda’s factory motocross bikes back then. The example shown here belongs to American Honda and was used by teenage sensation Marty Smith to win the ’74 125cc national championship.

Standing out in its all-red paint, Smith’s 125 was made by Honda Racing Corporation (HRC) in Japan as a pure racer. Various experimental parts were supplied to the race team throughout the year, which meant the bike could be quite different from one race to another. Even the chrome-moly steel frames varied greatly. Current Honda Motocross Race Manager Dave Arnold, a works mechanic during the early Seventies, laughs when he talks about the special frames of the day: “The factory frames held up fairly well on the smooth American tracks, but we broke one a race while racing on the rougher tracks in Europe. Every replacement frame was a little different than the one it replaced, nothing ever fit, we were always cutting off engine-mounting plates and re welding them to get the engine to fit the frame.”

Built in a time before the AMA’s current productionbased rules, the bike was fitted with many special parts. “The engines were full-factory,” says Arnold, “mostly magnesium and titanium. They had case-reed intakes, magnesium cases and covers, clutch hubs made of billet aluminum, and transmission gears made of special steel. A 29mm Keihin carburetor was used on most of American Honda’s racebikes; HRC experimented with mechanical fuel injection in Europe, but it didn’t work very good.

“Both hubs were magnesium with steel brake drums riveted inside, but front hubs distorted badly when tightening the spokes, so we normally used production front hubs in the U.S., although the bike you have for pictures has the factory hub on it. We had factory Showa forks with 35mm stanchions and 8 inches of travel. Factory air/spring shocks were supplied to us and they mounted farther forward on a 1inch-longer HRC aluminum swingarm that was painted red. Rear-wheel travel was around 6.5 inches. No one ever got the air shocks to work well, and we tried everything available for rear shocks back then. Konis were probably the best. The fork wasn’t much better, but it had large stanchion tubes, so I used to remachine Marzocchi fork dampers and fit them inside the Showa fork!”

The memory of this last bit of trickery brings a smile and a summation from Arnold. “We’ve learned a lot about motocross bikes in the last 20 years,” he says.

Ron Griewe

View Full Issue

View Full Issue