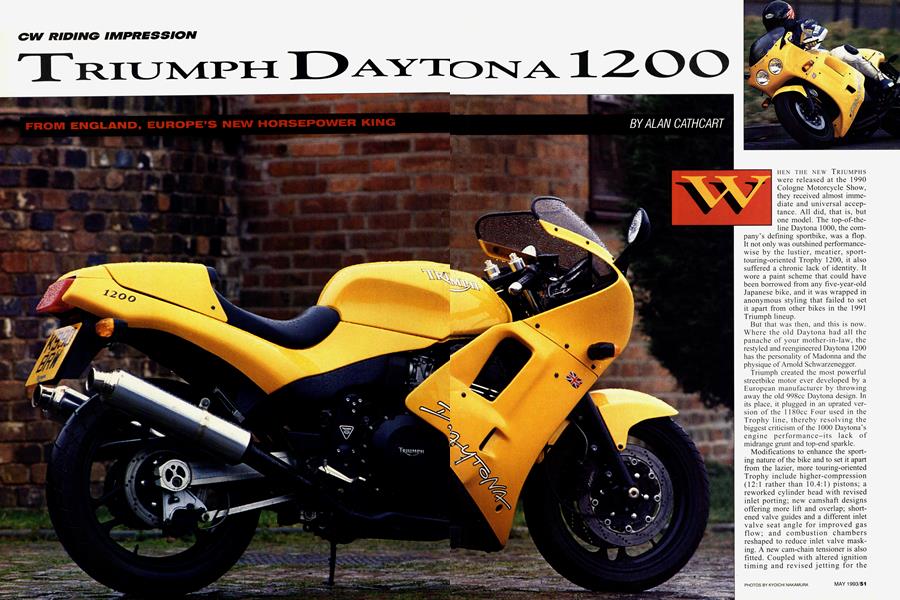

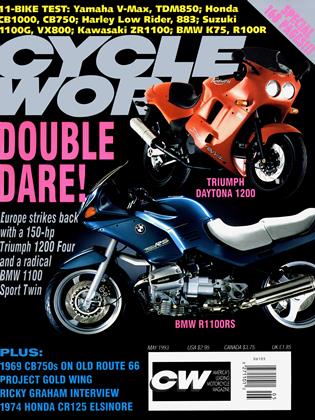

TRIUMPH DAYTONA 1200

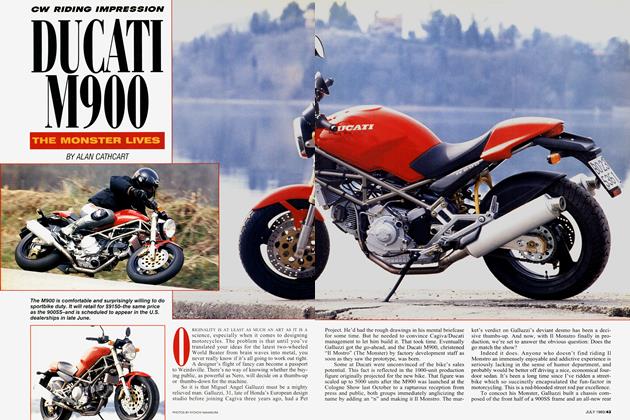

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

FROM ENGLAND, EUROPE'S NEW HORSEPOWER KING

ALAN CATHCART

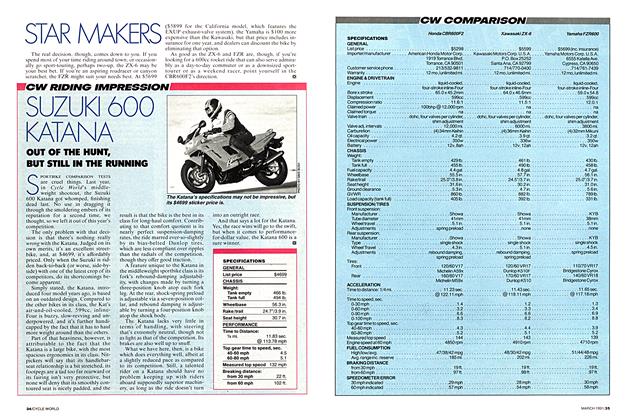

WHEN THE NEW TRIUMPHS were released at the 1990 Cologne Motorcycle Show, they received almost immediate and universal acceptance. All did, that is, but one model. The top-of-the-line Daytona 1000, the company’s defining sportbike, was a flop. It not only was outshined performancewise by the lustier, meatier, sporttouring-oriented Trophy 1200, it also suffered a chronic lack of identity. It wore a paint scheme that could have been borrowed from any five-year-old Japanese bike, and it was wrapped in anonymous styling that failed to set it apart from other bikes in the 1991 Triumph lineup.

But that was then, and this is now. Where the old Daytona had all the panache of your mother-in-law, the restyled and reengineered Daytona 1200 has the personality of Madonna and the physique of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Triumph created the most powerful streetbike motor ever developed by a European manufacturer by throwing away the old 998cc Daytona design. In its place, it plugged in an uprated version of the 1180cc Four used in the Trophy line, thereby resolving the biggest criticism of the 1000 Daytona’s engine performance-its lack of midrange grunt and top-end sparkle.

Modifications to enhance the sporting nature of the bike and to set it apart from the lazier, more touring-oriented Trophy include higher-compression (12:1 rather than 10.4:1) pistons; a reworked cylinder head with revised inlet porting; new camshaft designs offering more lift and overlap; shortened valve guides and a different inlet valve seat angle for improved gas flow; and combustion chambers reshaped to reduce inlet valve masking. A new cam-chain tensioner is also fitted. Coupled with altered ignition timing and revised jetting for the 36mm flat-slide Mikunis, these changes allow the uprated power unit to deliver a whopping claimed 147 crankshaft horsepower at 9500 rpm. This new engine also delivers a meaty 85 foot-pounds of torque at 7800 rpm-about 6 percent more than the 110-horsepower Trophy. A beefed-up clutch handles this extra push and shove, and this is mated to the six-speed gearbox common to all Triumph models.

This comprehensively reworked motor is fitted to Triumph’s trademark spine-frame chassis in its Daytona form-this means a sportier riding position and higher footrests than on the Trophy. The 43mm Kayaba fork (not the upside-down variety yet) has adjustable preload and 12stop rebound/compression damping adjustment, as well as stiffer springs than last year’s Daytona 1000. The Kayaba rear shock, which retains the four-stop rebound adjuster from the old Daytona and is easily accessible behind the frame upright on the right, also gets a stiffer spring. Nissin brakes are retained, with four-pot calipers gripping 12.2inch discs up front, and a floating 10-inch rear disc. Bridgestone BT50 Battlax radiais are fitted as standard, the rear an increasingly uncommon 18-incher with a 160/60 tire mounted on a 4-inch rim. Not a lot of rubber with which to connect 147 horses to the blacktop, you might think.

This engineering ensemble is clothed in the single most obvious difference from the old Daytona: The considerably beautified bodywork that Triumph dignifies with the phrase, “extensive cosmetic improvement.” Alterations include a lower, tinted screen, a curvier rear section and a bolt-on cover for the passenger seat. The bodywork comes in bright yellow, bright red or only fractionally less bright metallic blue, with a slash-cut black underside straight from the Ducati styling school. All this, combined with black wheels, black fork legs, black engine and black practically everything else except the alloy swingarm and race-type exhaust canisters, means that Triumph has created a clean, aggressive look that is distinctive without looking cheap. And while the shape of the fairing with its twin round headlights is still rather old-fashioned, it’s an acceptable feature of a bike that at last has a strong visual identity.

In spite of its earth-mover-sized horsepower, this is a surprisingly gentle bike to potter around on, as long as the engine is kept off the cams. And if the rider’s throttle hand does get overexcited, the rangy, 58.7-inch wheelbase helps get everything back in line quickly. That long wheelbase and equally conservative steering geometry-27-degree steering-head angle and 4.1 inches of trail-makes the Triumph reassuringly stable in slippery conditions, though it also allows noticeable understeer when you negotiate unknown backroad comers in part-throttle mode.

But the Daytona 1200 was bom for full-throttle use, and when that’s what you give it, it leaps forward with an unmistakable lilt to the exhaust note. In fact, from the moment you thumb the starter button, you know this is no two-wheeled sewing machine, but a lusty, eager musclebike. The Daytona is a much more visceral motorcycle than any of its counterparts; you can hear and feel the engine at work beneath you, playing a mechanical signature tune that is unique, reassuring, and, thanks to twin counterbalancers, relatively free from vibration. Personality, character, individuality—the Triumph’s motor has it in spades.

It also is undoubtedly potent, though this potency doesn’t assert itself till the tach needle is past halfway to the rev-limiter’s 10,000-rpm cutout. The Daytona is quite well-behaved at low rpm, but not very responsive. Once you’ve coaxed the engine up to 5000 rpm, though, it really takes off, accelerating hard and fast-forwarding through the surrounding countryside. This step in the power delivery is a smooth one; it won’t unhook the rear wheel at an awkward moment, but it endows the Daytona with brutal acceleration. If you want to zap a truck or sprint past a couple of cars on a country lane, it’s no good cracking the throttle wide open at 3500 rpm, because you won’t get the response you’re expecting. But whack the transmission down one or even two gears with the slightly harsh but completely positive gearchange, hoist the tach needle to five grand-plus, and you’d better hold on tight. Few production vehicles of any kind built for the street can deliver this kind of acceleration.

But don’t get the idea the Daytona is just a British V-Max, because in addition to making Porsche drivers feel inadequate, it’ll do a lot of other things very well. The whole bike has a very solid, taut feel about it. The suspension is perfectly set up, and in spite of the stiffer springs front and rear-surely one reason the bike feels so integrated and wellbalanced-the suspension response is outstanding on bumpy roads or cheapskate concrete freeways.

But if the suspension is responsive, the Daytona’s steering isn’t. Though the bike is superbly stable in fourth-gear sweepers and hugs the road well at speed, it isn’t very nimble at slower speeds, and requires you to use a fair bit of muscle as well as a shift of body weight to make it change direction at all quickly along a twisty country lane. It’s the only time the Daytona feels like a heavy bike, which at a claimed 502 pounds dry, it is. It is too bad Triumph didn’t dial up a little less trail and a steeper head angle to suit this model’s intended sporting mission.

Nevertheless, the Daytona can’t help but impress anyone who rides it. Even the bike you see here, a well-used preproduction version, had superb, lustrous paintwork, a nearperfect riding position, responsive brakes complete with stainless-steel lines, mirrors that were rock-steady at tonplus speeds, readable instruments (but no fuel gauge) and a fuel-tank shape that lets you rest your chest against it to grab a bit of shelter behind the screen at high speed. The footrest tabs are too long, so you scrape them very easily given the cornering angles the excellent Bridgestones are capable of once warmed up (which doesn’t take long), and the bike feels a bit wide across the flanks when you’re heaving it from side to side. But the overriding impression is that this is a motorcycle that was designed and developed by people who actually ride bikes themselves, who responded to the criticisms of the first committee-designed short-stroke Daytona 1000 by evolving the sort of bike they themselves would like to ride.

The Daytona 1200 will be built in a very small model run-only 300 bikes will be built this year, less than 5 percent of Triumph’s total production. Price will be £7899, or about $11,500. The 300 buyers who get these bikes will be the lucky ones. Triumph Motorcycles Limited has responded to its customers. Now it’s the customers’ turn to respond.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue