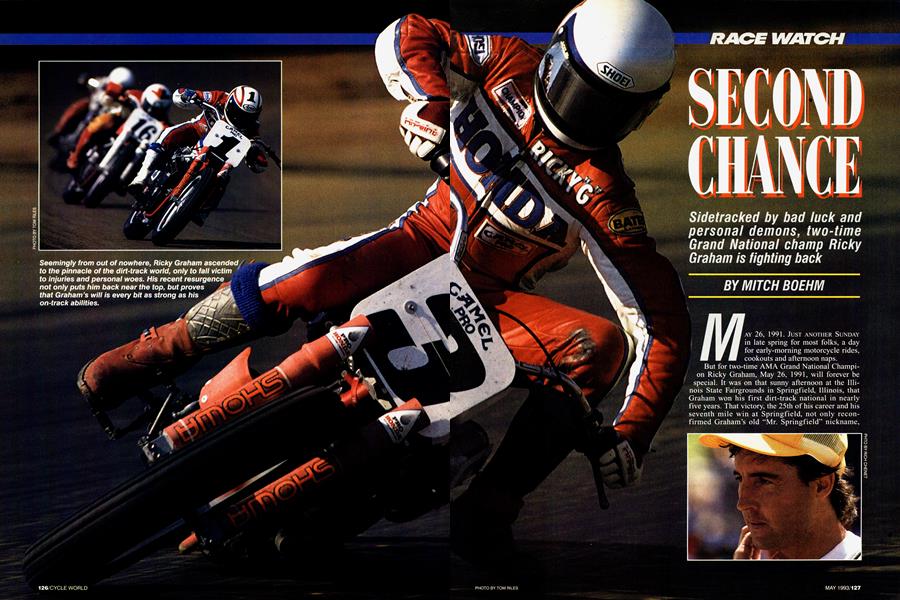

SECOND CHANCE

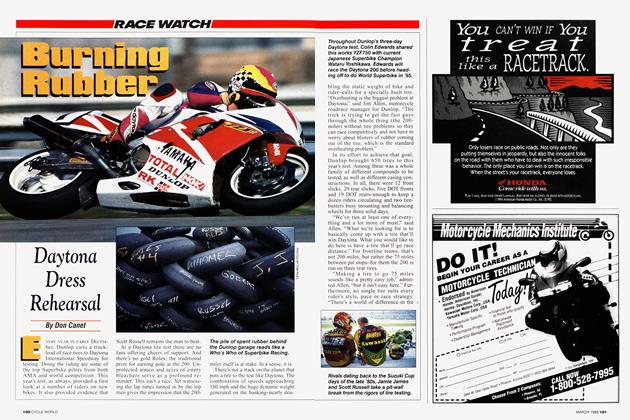

RACE WATCH

Sidetracked by bad luck and personal demons, two-time Grand National champ Ricky Graham is fighting back

MITCH BOEHM

MAY 26, 1991. JUST ANOTHER SUNDAY in late spring for most folks, a day for early-morning motorcycle rides, cookouts and afternoon naps. But for two-time AMA Grand National Champion Ricky Graham, May 26, 1991, will forever be special. It was on that sunny afternoon at the Illinois State Fairgrounds in Springfield, Illinois, that Graham won his first dirt-track national in nearly five years. That victory, the 25th of his career and his seventh mile win at Springfield, not only reconfirmed Graham's old "Mr. Springfield" nickname, but marked the starting point for a two-year comeback that concluded in a third-overall finish at the end of the 1992 season, just behind the factory Harley duo of Chris Carr and Scotty Parker. The Springfield victory proclaimed one fact loud and clear: Graham was back.

Up to the 1987 season, in which he finished fifth overall, “comeback” was not a word you would associate with Ricky Graham. Between 1980 and ’87, he forged a phenomenally successful dirt-track career, scoring a total of seven top-five overall series finishes, including a pair of Grand National Championships-the first in ’82 on a Tex Peel-built Harley-Davidson, the second in ’84 aboard a factory RS750 Honda.

But not long after those championship years, Graham’s career stalled. In ’86 and ’87, Graham tried to compete with only limited backing, which left him frustrated with his riding and financially strapped from paying the bills. Graham then switched to Mert Lawwill’s Harley team in ’88, though a host of mechanical failures put him out of the top 10. The next two years were no better, with Graham-back aboard Hondas-taking 12th and 13th, respectively. In the space of just a few years, Graham had gone from frontrunner to also-ran.

“Things were bad,” he says, slowly shaking his head, “I was worrying so much about getting to the races, keeping the bikes in shape and paying expenses that I couldn’t keep my mind on the racing. I got to the point where I hated going to the races.”

For Graham, the downward slide began in early 1985, the second year of his Team Honda contract, as he prepared to defend the number-one plate he had won in ’84 over teammate Bubba Shobert. At the season-opening TT at the Houston Astrodome, Graham collided in mid-air with Shobert and crashed violently, breaking his back, his thumb and a number of ribs. He rebounded quickly, only to break his left femur a few weeks later while training aboard a dirtbike at Kenny Roberts’ ranch. With help from Roberts (who had broken his femur a year earlier), Graham, sporting a 17inch rod in his leg, returned with a vengeance, scoring impressive wins in the latter part of the year at Peoria, Indianapolis, Springfield and San Jose. The ironman effort netted him fifth overall for the season, an amazing feat considering the severity of his injuries.

Impressive as it was, Graham’s lateseason charge wasn’t enough to keep him in the Team Honda camp. American Honda, beginning to feel the financial pinch of a shrinking U.S. market and a weak U.S. dollar, elected to field a one-rider dirt-track team for 1986. Bubba Shobert, who had won his first Grand National Championship in ’85, would be that rider. Just like that, Graham was out of a ride. Honda gave him a pair of RS750 racebikes to compete on, though from there on out, Graham was on his own.

“I was totally surprised,” Graham says. “Considering the success I had late in the season, I didn’t think I’d have any problem staying with Honda.”

Despite the setback, Graham persevered. “I felt I could carry on,” he says. “I figured we’d get a big sponsor.” Graham even went out and bought a motorhome and a new trailer in preparation for his ’86 campaign.

But the big sponsors never came, leaving Graham to fund most of his effort himself. He hired his brother to work on the bikes to minimize costs. Frustrated, riding poorly and losing money in a big way, Graham dropped to fifth in ’86, and fifth again in ’87. The lean years of ’88, ’89 and ’90 followed, years without a single national win and few top-10 finishes. Former national champ Ricky Graham was in a rut, and a deep one.

“I was at the end of my rope,” Graham says as he reflects on those frustrating years, “I felt like everything was going against me.”

Graham’s drinking didn’t help. Like many people who enjoy alcohol, he began drinking in his teens, and continued to drink socially through the years without problems. As he was winning dirt-track championships, swigging victory champagne or drinking beer on the weekend was standard operating procedure.

“Having a few beers with the guys after the races was so normal for me,” he says. “As far back as I can remember, there was always alcohol at the races. It was part of the whole scene. There was a party after every national.”

As his success grew in the early ’80s, Graham remembers feeling increasing pressure not to stand out, to be part of the group, and he went out of his way to hang out with fellow racers after the races. As always, the alcohol flowed freely.

“After I won my first title,” Graham says, “people started treating me differently, like I was on some pedestal or something. I felt uncomfortable with that. Having beers after the races was the way I could blend in, be a part of the group.”

Through the good years, the drinking wasn’t a problem. Graham was riding better than ever, and, except for his poor showing in 1981 when he left Tex Peel’s team and rode for Ron Wood, his career was progressing nicely.

But after the injuries of ’85 and the loss of his Honda ride, things began to change. The wins were coming less frequently. The sponsors weren’t coming around. The bills began piling up. And the drinking got worse.

“It was sort of a vicious cycle,” he says, “the worse I did, the more I’d drink. And the more I’d drink, the worse I did.

Despite the destructive behavior, Graham ran into a bit of good luck late in the 1990 season. Skip Eaken, a former factory Honda mechanic who built Bubba Shobert’s Hondas in ’84 and ’85, called Graham and asked if he would be interested in riding an Eaken-built Honda at the upcoming Indy Mile. His own program stumbling along without any semblance of success, Graham jumped at the chance. The result was a fourth at Indy, and a fourth later that season at Springfield. They were his best finishes of the year by far, and buoyed by the excellent results, he and Eaken made plans to make a serious assault on the 1991 championship series.

“It was a glimmer of hope for me,” Graham says. “It was exciting; I really wanted to win the 1991 championship. I thought we had a chance.”

The Graham/Eaken collaboration started well, with Graham scoring sixth-, seventhand fourth-place finishes in the opening four races. Graham followed that early-season success with the Springfield Mile victory in late May, his first national victory in nearly five years. “I wasn’t surprised,” he says, “I always knew I could win again.”

Despite the good finishes and a serious training schedule that had him in the best shape of his life, there was trouble. Graham missed the third race of the season at Pomona, California, too hungover, he says, to ride. And then just after the Indy Mile triumph, disaster struck. On his way home from Bubba Shobert’s bachelor party/golf tournament in Carmel, California, Graham was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol. Eaken had shown understanding over the Pomona incident, but upon hearing the news of the DUI arrest, he promptly kicked Graham off the team.

“At that point,” Graham says, “things were pretty bad. I remember telling myself, ’Ricky, you’re blowing your whole career. You’re blowing your whole life.’”

Things seemingly couldn’t get any worse, and Graham was ready to call it quits, to end his racing career for good.

“I figured it was all over,” says Graham, “and since I’d just won Springfield, I figured I might as well go out on top.”

But just a few days later, Graham got a call from Virginia contractor Johnny Goad, a hardcore follower of dirt-track racing and a long-time Ricky Graham fan. Goad offered to back Graham for the rest of the ’91 season, and a deal was made.

“I saw Ricky ride that massive Harley to victory at the Houston Astrodome TT in ’82,” Goad says, “and I couldn't believe it; he was amazing. I’d been working with another rider, but things just weren’t working out. I needed a change, and I felt that Ricky could win a championship.”

Graham’s finishes weren’t spectacular aboard Goad’s machines, though he did manage to finish ninth overall for the season despite the missed races.

But Graham’s big break, which came during the off-season, was realization: A realization that he had a problem, a realization that alcohol was negatively affecting his racing career as well as his life, and a realization that, with effort and help from his friends, he could turn things around and once again compete at the top. The drinking, Graham decided, would stop. For good.

“All of a sudden,” he says, “everything came clear and fell into place. I realized that I was sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

The off-season found Graham with newfound enthusiasm, an excitement he hadn’t had since the early years. There was no booze. Goad would build the bikes and back the team again in 1992. Close friend Danny Malfatti helped Graham keep to a strict training program, which included a healthy diet and massive amounts of time aboard a CR250 motocross bike. And then there was Graham’s fiance Leeza, who helped keep him focused. “I couldn’t have done it without them,” Graham says.

All the work and sacrifice paid off, too. Graham had his most consistent year ever in 1992. Though he won only one national, the nighttime mile at Syracuse, New York, his consistency netted him third overall at season’s end. “I felt better on the bike in 1992 that I ever have,” Graham says, “even in my championship years.”

More important than the racing is how the hard work and success helped Graham see himself differently. “I felt so bad during those years,” he said, “like everyone was staring at me and talking about me behind my back. These days, I feel so much better.”

So what’s in store for Graham in 1993? Plenty. He’ll again ride Goadprepared Hondas, and will team with rookie Brett Landes for UNDO Racing, a team supported by Landes’ father, Jim.

“Our plan is to do a thoroughly professional effort this year,” Graham says with obvious enthusiasm. “We need to attract more sponsorship, but I think we’ll do well. I’m looking forward to it.”

Graham will also contest the Harley-Davidson 883 TwinSport Series, which will consist of roadraces as well as dirt-track events.

And after that? Graham, now 34, talks about retiring someday and running a dirt-track school, but don’t count on that to happen too soon. Based on his 1992 season, it’s clear that there’s a lot of racing still left in Ricky Graham.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue