CYCLE WORLD TEST

YAMAHA WR 250

A WINNER AT LAST

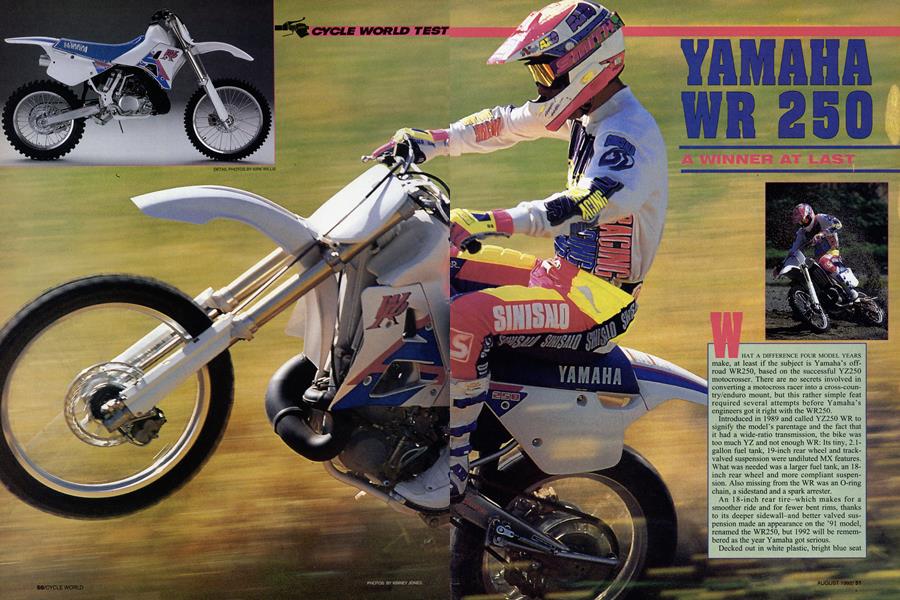

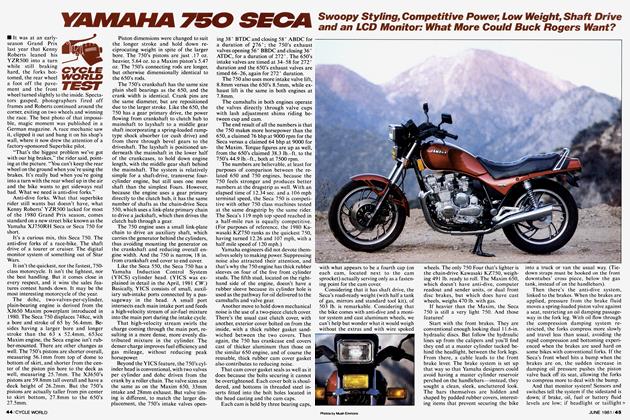

WHAT A DIFFERENCE FOUR MODEL YEARS make, at least if the subject is Yamaha’s offroad WR250, based on the successful YZ250 motocrosser. There are no secrets involved in converting a motocross racer into a cross-country/enduro mount, but this rather simple feat required several attempts before Yamaha’s engineers got it right with the WR250.

Introduced in 1989 and called YZ250 WR to signify the model’s parentage and the fact that it had a wide-ratio transmission, the bike was too much YZ and not enough WR: Its tiny, 2.1gallon fuel tank, 19-inch rear wheel and trackvalved suspension were undiluted MX features. What was needed was a larger fuel tank, an 18inch rear wheel and more compliant suspension. Also missing from the WR was an O-ring chain, a sidestand and a spark arrester.

An 18-inch rear tire-which makes for a smoother ride and for fewer bent rims, thanks to its deeper sidewall-and better valved suspension made an appearance on the ’91 model, renamed the WR250, but 1992 will be remembered as the year Yamaha got serious.

Decked out in white plastic, bright blue seat and blue-and-purple decals, the WR now has a 3.4-gallon fuel tank. The tank’s added width is readily apparent as soon as the rider climbs aboard. Moving forward on the WR’s flat, motocross-style seat in order to load the front wheel for a tight comer is more difficult now, but the increased range the bigger tank brings is worth that minor inconvenience.

When it’s time for a trail-side break, the WR250’s new swingarm-mounted sidestand will also be appreciated. This stout stand, while rather heavy, is designed so it doesn’t readily catch on rocks and brush. Competition riders who dislike stands can simply remove the WR250’s by unscrewing two bolts.

Not so easily noticed is an O-ring chain. Durability, low maintenance and minimal stretch are advantages O-ring chains have over non-O-ring chains-all off-road bikes should be so equipped. When the chain needs adjustment, new snail-type adjusters make the chore easy and quick.

Plush suspension via a new KYB fork and a KYB single shock, both carefully valved for cross-country riding, is another thing that Yamaha got right this year. Indeed, after setting the rear-suspension sack at 4.0 inches, we never touched the fork or shock again, even though each is fully adjustable for rebound and compression damping.

None of our riders registered any complaint against the WR’s suspension, a rare occurrence for an off-road testbike. Small bumps, ledges and tree roots get swallowed up, > there’s no midrange harshness, and both ends are resistant to bottoming on hard hits.

Things aren’t quite so rosy in the turning department, at least in the bike’s as-delivered form. The WR resists quick direction changes, and was nearly impossible to keep in rain ruts-the front wheel constantly tried to climb out of them. We remedied both conditions by raising the fork tubes 10mm in the triple clamps. Straight-line stability at speed, long a Yamaha trademark, remained good, even after we altered the fork.

Another WR constant is the potent, 249cc, YZ-derived engine, which boasts new cylinder ports, refined combustion-chamber shape, a redesigned pipe and a round-slide 38mm Mikuni carburetor for ’92. Additionally, the WR’s already wide-ratio transmission has wider-ratio third and fourth gears.

The new gear spacing greatly improves the WR’s performance, especially when upshifting on a long, steep hill: There’s never any engine bog and each higher gear feels like a fluid extension of the previous cog, with a good spread of power between gears. Shifting is smooth, easy and positive, too. The clutch pull is light and its engagement is quick and solid, just like that of the YZ250 MXer. This quick clutch action was favored by hard-riding racer types, while some of our less aggressive test riders wanted a more progressive engagement.

The WR’s powerful, motocross-tuned engine drew its share of complaints from slower riders, too, all directed toward the engine’s stepped powerband. The WR’s smoothpulling, easily controlled low-rpm power is followed by a sudden switch into a knob-shredding midrange mode. Although better riders learn to use this power leap to their advantage-exploding out of bermed turns, lofting the front wheel over logs, etc.-this rapid blast of horsepower causes rear-tire spin that detracts from control when negotiating slippery uphills, or when crossing rocky terrain.

Modifying the WR for a smoother power flow may be as inexpensive and easy as adding a spark arrester (the WR still lacks one, a serious omission on a bike that will be used for trail rides), or it may be as expensive and involved as changing to an aftermarket pipe and silencer.

A less bothersome problem is rear-brake chatter. Although both disc brakes are strong and powerful, and provide good feedback, the rear binder chatters when braking across rippled ground or when descending rough downhills.

Overall, though, the 1992 Yamaha WR250’s good points far outnumber its faults. The WR is well finished, its engine starts easily, its seat is firm and shaped nicely, its suspension is near-ideal, and the bike feels solid and is fun to ride. If Yamaha elects to further improve the WR in 1993, building on an already excellent base, the WR250 will be a serious contender for best enduro-bike awards. ®

YAMAHA

WR250

$4299