Numb Bum Ice Marathon

Twenty-four hours on the rocks

RACE WATCH

MARVIN ROLOF

IT'S SHOCKING HOW COLD YOU GET RACING A MOTORcycle on ice. Imagine going 100 mph through the winter wind, hours after the sun has set and the mercury has plummeted to 20 below zero. The term "wind chill" doesn't begin to do it justice.

But it's even more shocking how quickly you learn to ignore the cold, at least when you're racing in the Numb Bum 24-Hour Ice Marathon, a decade-old fundraiser invented by the Grand Prairie Motorcycle Club and now hosted by the Fairview College Foundation, of Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

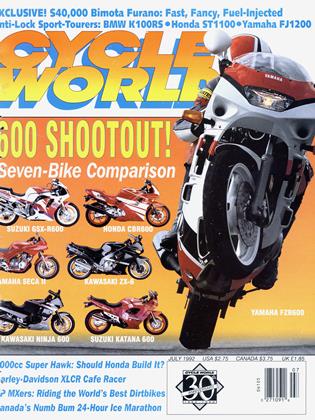

The concept is simple: one bike per team, as many team members as you want, with the object being to complete as many laps as possible between noon Satur day and noon Sunday. Like many simple concepts, though, it becomes more complicated when you add all the facts. Like the date: the last weekend in February, tra ditionally the coldest, most miserable height of winter. And the location: frozen George Lake in northern Alberta. Several days before the event, snowplows begin snaking back and forth across the lake, cutting out the 30-foot-wide track. The only course markers are the 4-foottall banks of snow left in their wake, looking more like walls to the riders, and ensuring that every corner is at least partially blind. This year, the organizers marked many of the tighter corners with signs to help the riders remember the track layout.

Good thing, too. More riders turn up every year, so to keep the track from being too badly chewed up and the overall speed down, the track gets longer and the layout gets tighter. With a lap being 7.5 miles long with 81 corners, this year's track was a challenge to the memories of even the most experienced Numb Bum com petitors. A typical lap took about 10 minutes, though some of the faster teams managed it in just over eight.

Each year prior to the race, ru mors of special happenings begin to circulate. And this year, some of those rumors actually became fact. A television sports network showed up to film the event. Even more surprising was the arrival of Eve! Knievel. The once-famous motorcycle dare devil spent the weekend staying out of the cold (with his bones, who wouldn't?) but seemed jovial otherwise, giving speeches and signing autographs and even waving the checkered flag.

For our team, jokingly named The Real Men, the Numb Bum has be come the site of an annual reunion, a justifiable reason to drive halfway across Alberta, spending time and money none of us can really spare. Our first time out, four years ago, was a last-minute excuse for a gather ing of old college friends, and the ac tual riding of the event was an afterthought. In fact, only one of us had ever ridden on the ice. -

Wflicli explained our cnoice or ma chinery. While most everyone runs a big, single-cylinder four-stroke, we enter a 1981 Yamaha Seca 750. As you might suspect, we give up a little in handling and traction. But we de fend our choice on the grounds that the Seca is almost maintenance-free, thanks to its shaft drive and spokeless wheels. And we have lots of straight away speed.

Of course, the Seca has had its share of difficulties. Like in Hour One of our first year, when we deduced that the Yamaha was lacking in brakes. We resorted to dumping the clutch in first gear to slow ourselves for the cor ners-gotta love those rev-limiters.

Or in Hour 16, when our rear tire, fatigued by holding 400 pounds of metal in semi-contact with the ice without the aid of air (it had been flat for six hours), finally blew out a side wall. Team quote of the year: "It han dled okay at 90 but slow it down to 30 and it's a real handful."

Then there was Hour Two of the sec ond year, when a badly slipping clutch left us screaming down the straights at almost a standstill. An emergency clutch swap was performed as the Seca laid on its side like an injured horse. Hot engine cases melted into the ice as confused hands alternated between cold tools and hot parts. "Cold wrench! Hot plates!"

And Hour 23 of the third year, when we were forced to fix a broken throttle cable with vise-grips. No, don't ask.

Every year, a crash has broken our headlight brackets. We've always managed to salvage the lights, but have never been able to make them shine forward. The winter skies are beautiful at night. We know; it's all we ever saw.

This year, we swore Things Would Be Different. No more lack of lights, no more nagging problems an4, above all, no more major problems. We would tear down and inspect the en gine, and do away with the stock headlight in favor of dual driving lights on rubber-mounted brackets.

Like the best-made plans of all weekend warriors, however, things soon went from bad to worse. Not only was the motor in need of a long list of parts, but those parts were all on back order. So we bought a used Maxim engine that took only minor motor-mount modifications to install. Meanwhile, a communication confu sion over who was to acquire the lights almost left us with none.

The only thing we managed to get right were tires. After years of run ning a heavy bike with lots of torque, we've learned what works and what doesn't~ just running screws into a tire isn't enough.

One tire takes about six hours to build. The procedure goes something like this: Take a motocross tire, find a street tire that's just a bit smaller, and cut the sidewalls off of the latter to serve as a liner. Run the mandatory 1.5-inch-long ice-racing screws through both the tire and the liner, far enough to hold in the cords of both, but no so far that you puncture the tube. A tire takes approximately 800 screws, each with its inside tip dulled to ensure that 24 hours of pounding won't work it through to the tube. You then silicone the edges of the liner and wrap the tube with an old tube and duct tape for added protection. And finally, just to be safe, you run short screws through the rim and into the sidewall to lock the bead.

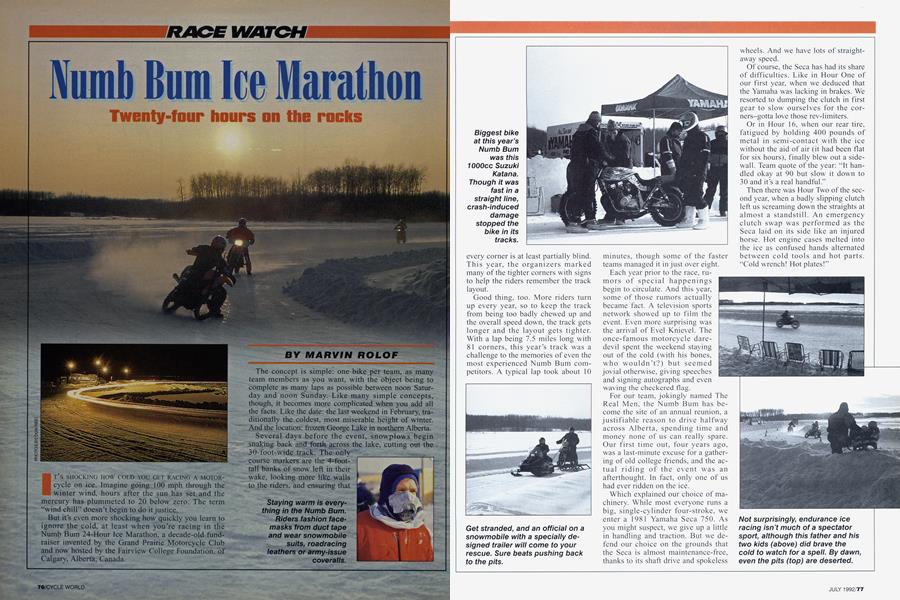

First time out, we were considered certifiably insane to run a multi-cylin der, 750cc streetbike. But this year, there were several converted street ma chines present. The Fire On Ice team brought a 1000cc Suzuki Katana, top ping the GSX-R750 of two years ago as the fastest straightaway machine. They soon found out, however, what we've known for some time: Most straightaways end in corners.

What does seem to hold potential are the hybrids that are beginning to appear. The most interesting of these was ridden by the Odyamaski's Re venge team, a combination of a 440 Ski Doo snowmobile motor in a Kawasaki KX motocross chassis. Had it not been for teething problems with the variable-speed belt system (which jackshafted to a chain drive), it would have done considerably better.

Another curious arrival was a Yamaha RZ350 motor in a KX500 frame, a creation of the No Fear team. After some jetting changes and a brake-line failure, the bike worked well. Their biggest problem seemed to be the dreaded, early-morning "Where did all my teammates go?" syndrome.

Team Harley-Davidson was pre sent, as always, this time running a Sportster that reportedly revved to seven grand and cornered like it was on sideways rails. Dressed mostly in leather and beards, these guys were diehard bikers. If they weren't, they would have died four years ago when they ran an 80 cubic-incher on stud ded street tires.

The Blind Faith team returned, and for the second year in a row ran a Norton motor in a Yamaha XT500 frame. And for the second year in a row, they had clutch and coil prob lems. They provided some excitement this year, however, when their throttle cable broke, leaving the carbs stuck wide-open. Using the kill button in the corners let the wide-eyed rider bring the bike back to the pits without incident.

Still, they had better luck than we did with our used Maxim motor. Dur ing hour six, the tranny reverberated with a mighty "POP" and a lovely backdrop of grinding noises. Drop ping the oil pan, we found several large chunks of what appeared to be second gear. We managed to locate a motor of similar denomination and, a mere five hours later, the Seca's open headers once again echoed off the trees surrounding the lake. Until one of the headers broke off, at which time the exhaust took on a distinct "underwater duck" tone at low revs, where we spent more time than we would have liked because our bor rowed tranny soon refused to engage second gear.

Things were not a total disaster. After all, we still had lights-or at least we did until they began to get dimmer and dimmer, and the handle bar warmers stopped working, and we were forced to disconnect one of the lights to save our charging system.

As darkness falls so does the tern perature, bringing a new set of chal [enges. Enthusiasm gives way to latigue and riders sneak off to sleep anywhere they can. The smart ones look for heated campers. "Hi, mind if sleep here?" Most people are too cold and tired to argue.

I fle remaining riders bucKle clown for the nightshift, telling themselves they'll catch up on sleep later. The morning sun brings all the riders back with renewed enthusiasm; and it al ways seems to rub off on the night shift guys, who never do get a chance to sleep. They're like little kids, not wanting to go to bed because they might miss something.

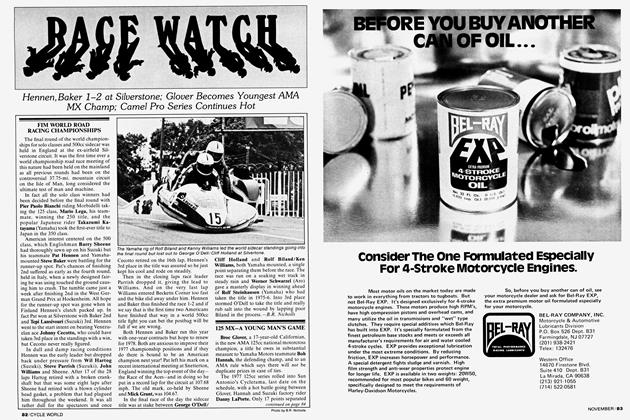

In the true spirit of the Numb Bum, we struggled on to the bitter end-sort of. An electrical failure on the last lap left us stranded. Thankfully, we were rescued by one of the snowmobiles that constantly scout the course. Talk ing the driver into pulling us across the finish line let us take the check ered flag.

For the second time in three years, Wendell's Wacky Wheelers finished with the most laps, taking the overall win and topping the Over-350cc class. They stayed fast and consistent on their Yamaha XT600, completing 129 laps for a distance of 1002 miles.

The efficient team from Scanalta Power, a Yamaha dealer in nearby Hines Creek, won the Under-350cc class, and finished fifth overall on a blazingly fast Yamaha WR250 (suf fering only one seizure, down two from last year).

The top money-raisers were the De lightful Distractions, an all-female team to whom Pepsi had given the closest thing to a factory ride that the Numb Bum has ever seen: matching riding suits. They completed 53 laps to raise $4500. The foundation esti mates that more than $100,000 has been raised over the last nine years, with another $40,000 raised this year alone. With the provincial govern ment matching the funds raised, ap proximately $80,000 will go to adult literacy programs and the Peace Country Regional Science Fair.

Meanwhile, the Fido Dido Fun Ones didn't fare as well. They suf fered three injured riders-one with a broken leg, one with a broken rib, and one with a broken collarbone-a high er injury count than the past three years combined, and all on one team.

As serious as the racing is, the dogeat-dog attitude of other forms of rac ing isn't found or missed at the Numb Bum. Everyone helps everyone. We've borrowed lightbulbs, tape, a clutch and even a transmission from other teams. And we've lent screws, tools and manpower in return. The Numb Bum isn't about winning; it's about finishing, and having fun along the way-sort of like life. That's why the Numb Bum might just be the per fect race. Because, like life itself, it isn't really a race.

It's a matter of survival.

Marvin Rolof is a 25-year-old motor cycle mechanic who lives in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. An Intermediate motocrosser, Rolof recently complet ed a professional writing program at Mount Royal College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAndy Rooney Rides

July 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Whites of Their Eyes

July 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Matter of A Pinion

July 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1992 -

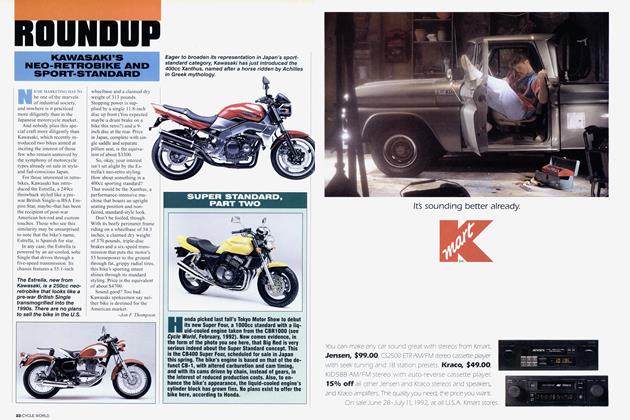

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki's Neo-Retrobike And Sport-Standard

July 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuper Standard, Part Two

July 1992